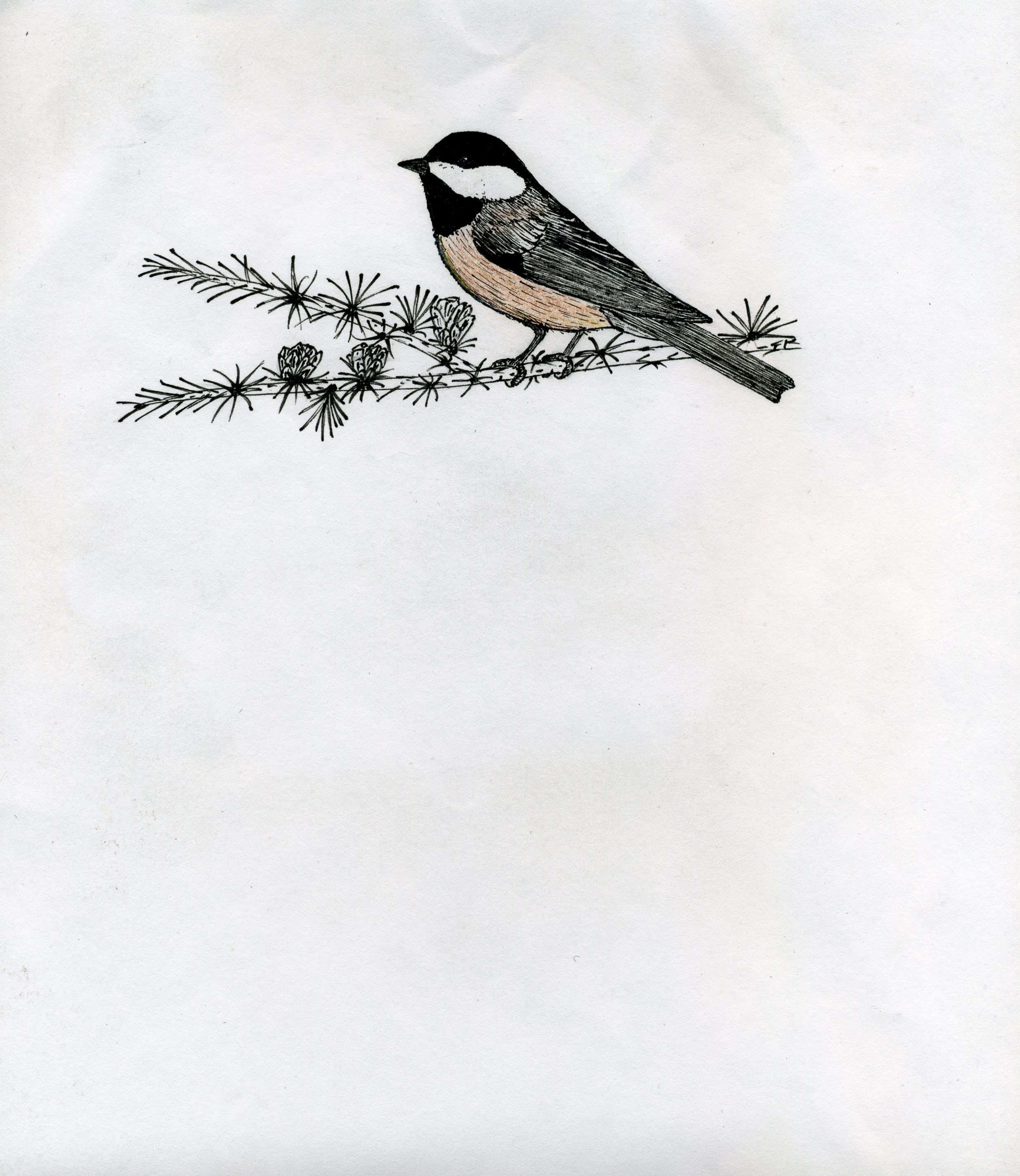

Black-Capped Chickadee Cikepiipiiq

Most bird species in Alaska ebb and flow like the tide. In the spring they migrate up to Alaska, then, all too soon, they depart for warmer climes down south. Not so with Black-capped chickadees. They remain ever faithful to their home in the northern forests and taiga country. I don’t mean to say that the species isn’t found elsewhere. In fact, it ranges from Alaska to Newfoundland, and all the way south to New Mexico and North Carolina, but, as with only a handful of other species in Alaska, individuals rarely leave the neighborhood they were born in.

They are also easy to recognize, for at all times of the year both sexes wear an identical black cap and bib. They also have the same characteristic call 365 days a year. Their common name derives from the sound of their most frequent call, “chick-a-dee-dee-dee.” The naming of a bird after the sound it makes is referred to as onomatapoeia, and occurs often also in the Yupik language, although in this case the chickadee’s voice is translated as, “cikepiipiiq.” As you might guess, the Yupik name is also, “cikepiipiiq.” No matter how it’s written, chickadees don’t seem to care. They just go on using it the way they always have, to keep track of each other while feeding in the woods. And its not their only call. Especially in winter and spring, they have an even sweeter song that goes, “hear, hear-me...spring, com-ing.” And, according to ornithologists, there are as many as 15 other calls.

Black-capped chickadees belong to the Titmouse family, and their scientific name is Parus atricapillus. There are 65 other species in their family in both the Old and New World, three of which live here in Alaska, including the Boreal chickadee, Chestnut-backed chickadee, and the rare Gray-headed chickadee, also known as the Siberian Tit.

Black-caps are the most “friendly” of the four Alaskan species of chickadee, which explains why they readily eat from backyard feeders. They are also among the best winter survivalists of any of the bird species who stay here year around, fattening themselves on foods rich in oils and caching much of it in locations their brains are programmed to remember. They get through the frigid Alaskan nights by not only taking refuge in tree cavities, sometimes in small groups, but by going into a state of “regulated hypothermia,” dropping their body temperature more than 50 degrees Fahrenheit. This way they don’t have to use as much energy from their fat reserves to heat their bodies.

As you might expect for such a hardy bird, chickadees have other cold-weather adaptive strategies. By shivering their muscles, they use stored fat reserves to generate heat, thereby regulating their body temperature when cooling down at night. During winter they have denser plumage than most other birds their size, and, although this makes them less adept flyers at that time, it provides them with more insulation, which can be fluffed up for additional warmth when temperatures plummet as low as 60 below zero. Brrrrr!

Black-capped chickadees usually form permanent pair bonds in the fall between single males and females. They remain together as part of a winter flock, but with the harbingers of spring the pair establishes a nesting territory, which both birds defend. At this time the male often feeds the female as a prelude to nest building and mating.

Although nest sites are usually in natural tree cavities enlarged by both male and female, sometimes old woodpecker holes or nesting boxes are used. The nest itself is built by the female of mosses and other plant fiber, and is lined with feathers and animal fur.

Six to ten white, brown-dotted eggs are laid. These are brooded only by the female for 12-13 days, and when the female leaves the nest she covers the eggs with soft nest material to keep them warm. The male often feeds the female during incubation. After the eggs hatch, the female remains with the young most of the time at first, while the male brings food to the nest. Later, both parents feed the hatchlings. The young leave the nest about 16 days after hatching. The pair usually raises only one brood each year, and this little family will hang around together all winter long until nesting time arrives again in spring.

If you want to attract these sociable birds during winter, put out a feeder in your yard. Place it close to trees so birds can easily escape predators, and about 30 feet away from your windows to prevent fatal crashes. Also place suet or peanut butter balls in similar locations. Keep the feeders clean to prevent birds from getting sick.

One final tidbit for those who wish to attract these little guys closer while walking or skiing in the woods or wherever you might run across them. Learn to “spish.” Call a local Audubon Society member to learn how.

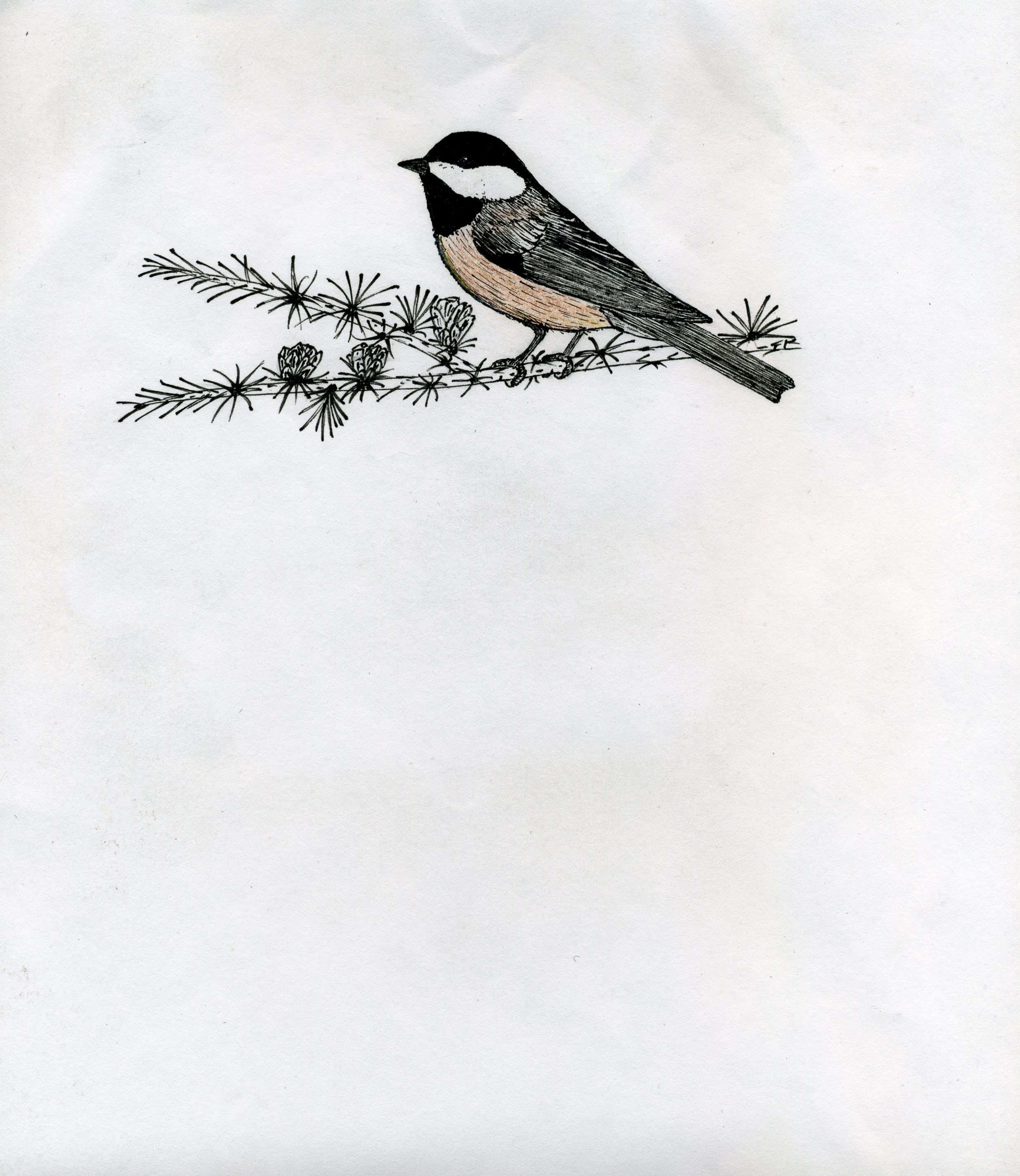

Most bird species in Alaska ebb and flow like the tide. In the spring they migrate up to Alaska, then, all too soon, they depart for warmer climes down south. Not so with Black-capped chickadees. They remain ever faithful to their home in the northern forests and taiga country. I don’t mean to say that the species isn’t found elsewhere. In fact, it ranges from Alaska to Newfoundland, and all the way south to New Mexico and North Carolina, but, as with only a handful of other species in Alaska, individuals rarely leave the neighborhood they were born in.

They are also easy to recognize, for at all times of the year both sexes wear an identical black cap and bib. They also have the same characteristic call 365 days a year. Their common name derives from the sound of their most frequent call, “chick-a-dee-dee-dee.” The naming of a bird after the sound it makes is referred to as onomatapoeia, and occurs often also in the Yupik language, although in this case the chickadee’s voice is translated as, “cikepiipiiq.” As you might guess, the Yupik name is also, “cikepiipiiq.” No matter how it’s written, chickadees don’t seem to care. They just go on using it the way they always have, to keep track of each other while feeding in the woods. And its not their only call. Especially in winter and spring, they have an even sweeter song that goes, “hear, hear-me...spring, com-ing.” And, according to ornithologists, there are as many as 15 other calls.

Black-capped chickadees belong to the Titmouse family, and their scientific name is Parus atricapillus. There are 65 other species in their family in both the Old and New World, three of which live here in Alaska, including the Boreal chickadee, Chestnut-backed chickadee, and the rare Gray-headed chickadee, also known as the Siberian Tit.

Black-caps are the most “friendly” of the four Alaskan species of chickadee, which explains why they readily eat from backyard feeders. They are also among the best winter survivalists of any of the bird species who stay here year around, fattening themselves on foods rich in oils and caching much of it in locations their brains are programmed to remember. They get through the frigid Alaskan nights by not only taking refuge in tree cavities, sometimes in small groups, but by going into a state of “regulated hypothermia,” dropping their body temperature more than 50 degrees Fahrenheit. This way they don’t have to use as much energy from their fat reserves to heat their bodies.

As you might expect for such a hardy bird, chickadees have other cold-weather adaptive strategies. By shivering their muscles, they use stored fat reserves to generate heat, thereby regulating their body temperature when cooling down at night. During winter they have denser plumage than most other birds their size, and, although this makes them less adept flyers at that time, it provides them with more insulation, which can be fluffed up for additional warmth when temperatures plummet as low as 60 below zero. Brrrrr!

Black-capped chickadees usually form permanent pair bonds in the fall between single males and females. They remain together as part of a winter flock, but with the harbingers of spring the pair establishes a nesting territory, which both birds defend. At this time the male often feeds the female as a prelude to nest building and mating.

Although nest sites are usually in natural tree cavities enlarged by both male and female, sometimes old woodpecker holes or nesting boxes are used. The nest itself is built by the female of mosses and other plant fiber, and is lined with feathers and animal fur.

Six to ten white, brown-dotted eggs are laid. These are brooded only by the female for 12-13 days, and when the female leaves the nest she covers the eggs with soft nest material to keep them warm. The male often feeds the female during incubation. After the eggs hatch, the female remains with the young most of the time at first, while the male brings food to the nest. Later, both parents feed the hatchlings. The young leave the nest about 16 days after hatching. The pair usually raises only one brood each year, and this little family will hang around together all winter long until nesting time arrives again in spring.

If you want to attract these sociable birds during winter, put out a feeder in your yard. Place it close to trees so birds can easily escape predators, and about 30 feet away from your windows to prevent fatal crashes. Also place suet or peanut butter balls in similar locations. Keep the feeders clean to prevent birds from getting sick.

One final tidbit for those who wish to attract these little guys closer while walking or skiing in the woods or wherever you might run across them. Learn to “spish.” Call a local Audubon Society member to learn how.