UAF photo by Leif Van Cise.

Wright Air Service employees in Fairbanks load a Cessna Grand Caravan bound for the

Yukon River village of Nulato on the morning of Jan. 23, 2024, when the temperature

was about minus 35 Fahrenheit.

By Sam Bishop

Jim Buckingham ’00 often flies his twin-engine Piper Aztec between the Anchorage area and southwestern Alaska where his family is temporarily housed this winter in the village of Napakiak.

Jim Buckingham leans on his Piper Aztec at the runway in Napakiak.

The flat, treeless tundra around the village is drenched with lakes, swamps and winding rivers. The Bering Sea, about 50 miles down the Kuskokwim River from Napakiak, supplies frequent clouds, rain and snow.

“Bad visibility, low overcast, mist, freezing fog — all those things sometimes make the weather out here just terrible,” Buckingham said. “You’re better just to wait, and sometimes you’re just waiting for awhile.”

Napakiak, with about 330 residents, lies “about 5 minutes flight time south of Bethel,” the larger regional hub village, Buckingham said.

Using flight time to mark distance comes naturally to the 65-year-old retired Army lieutenant colonel. Buckingham earned a pilot’s license at 18 and has flown since. He bought the Aztec in 2019.

But, in a state permeated by flying, neither Buckingham’s longevity as a licensed pilot nor his plane distinguishes his aviation career.

Rather, his legacy rests on three sets of cameras, the precursors to those at Napakiak and elsewhere, that he hooked up to the internet while a Ph.D. student at UAF in the late 1990s. Buckingham wanted to see if the cameras could improve the safety of flying small planes in rural Alaska.

They did.

The camera system, now greatly expanded and operated by the Federal Aviation Administration, allows pilots — and anyone with an internet connection — to see photos of recent weather conditions at more than 230 locations across Alaska. The FAA recently decided to add another 160 camera sites, mostly in the Lower 48, extending the safety benefits across the nation.

Finding the vision

Buckingham answered his cell phone outside his Napakiak home on Jan. 12 but had to hang up a moment later. He had an urgent chore in the sub-freezing weather — using a portable Honda pump to move water into his house from a 250-gallon tank in the back of a Dodge Dakota truck. The water had come from the village’s central well.

When he got back on the phone, Buckingham said his Ph.D. project sought to help pilots flying to places like Napakiak by giving them real-time pictures of the weather.

“It's just the old adage that a picture is worth a thousand words,” he said.

In the 1990s, he noted, the FAA had reduced its network of human-staffed flight service stations across Alaska. That left aviation weather analysis more dependent upon the FAA’s and National Weather Service’s automated weather stations, which convert instrument data to voice or text messages available by phone, radio or computer.

The automated stations operate at airstrips and other locations across Alaska, and they provide essential information, Buckingham said. But they have well-known limitations and weak points.

By the time he began pondering the situation in the late 1990s, the FAA had installed a few remote cameras in Valdez and Anchorage. But Buckingham thought the technology could do better.

“Basically, I came up with this idea that what the FAA was doing in very small parts … I wanted to do full time as a graduate student trying to earn my Ph.D.,” he said. “And that was to improve the weather reporting in rural Alaska through using vision — and specifically cameras.”

More than 25 years later, Alaska’s pilots describe the expanded system as a highly useful tool in helping them decide when to fly. And data indicates the cameras have significantly increased the safety and efficiency of air travel in small aircraft across the state, as Buckingham had hoped.

Adding to an automated system

Steven Green, operations training manager for Wright Air Service in Fairbanks, describes how the company’s pilots use the Federal Aviation Administration’s weather camera system.

Steven Green, carrying a beaver fur hat to block the morning’s minus 35 temperature, dropped into a seat in front of three large computer screens at Wright Air Service in Fairbanks on Jan. 23. The company flies about 30 aircraft, mostly Cessna Grand Caravans, across northern Alaska.

“So this is the planning area, and this is where we'll interact with weather information,” Green said. “The weather cameras are a critical function of that.”

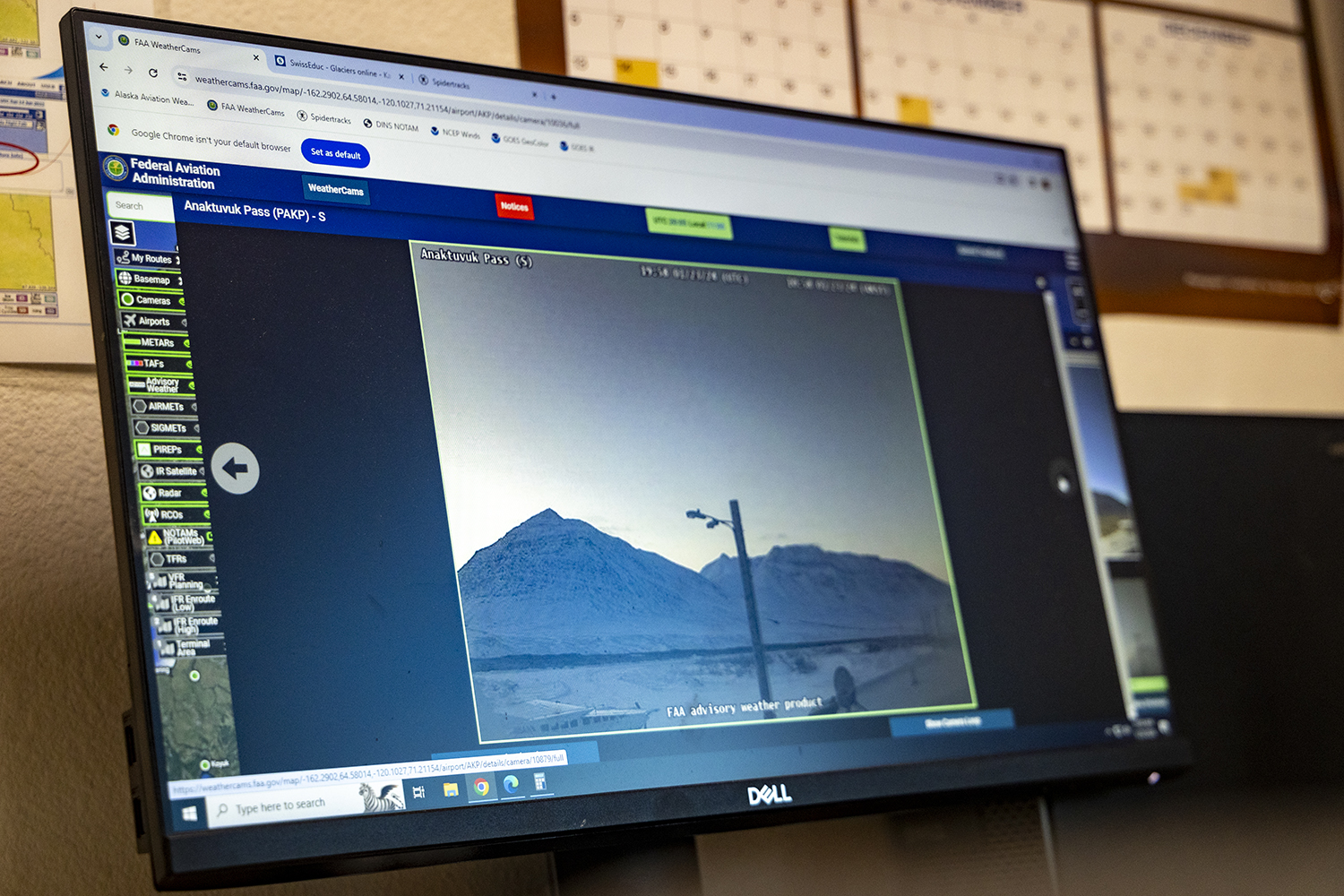

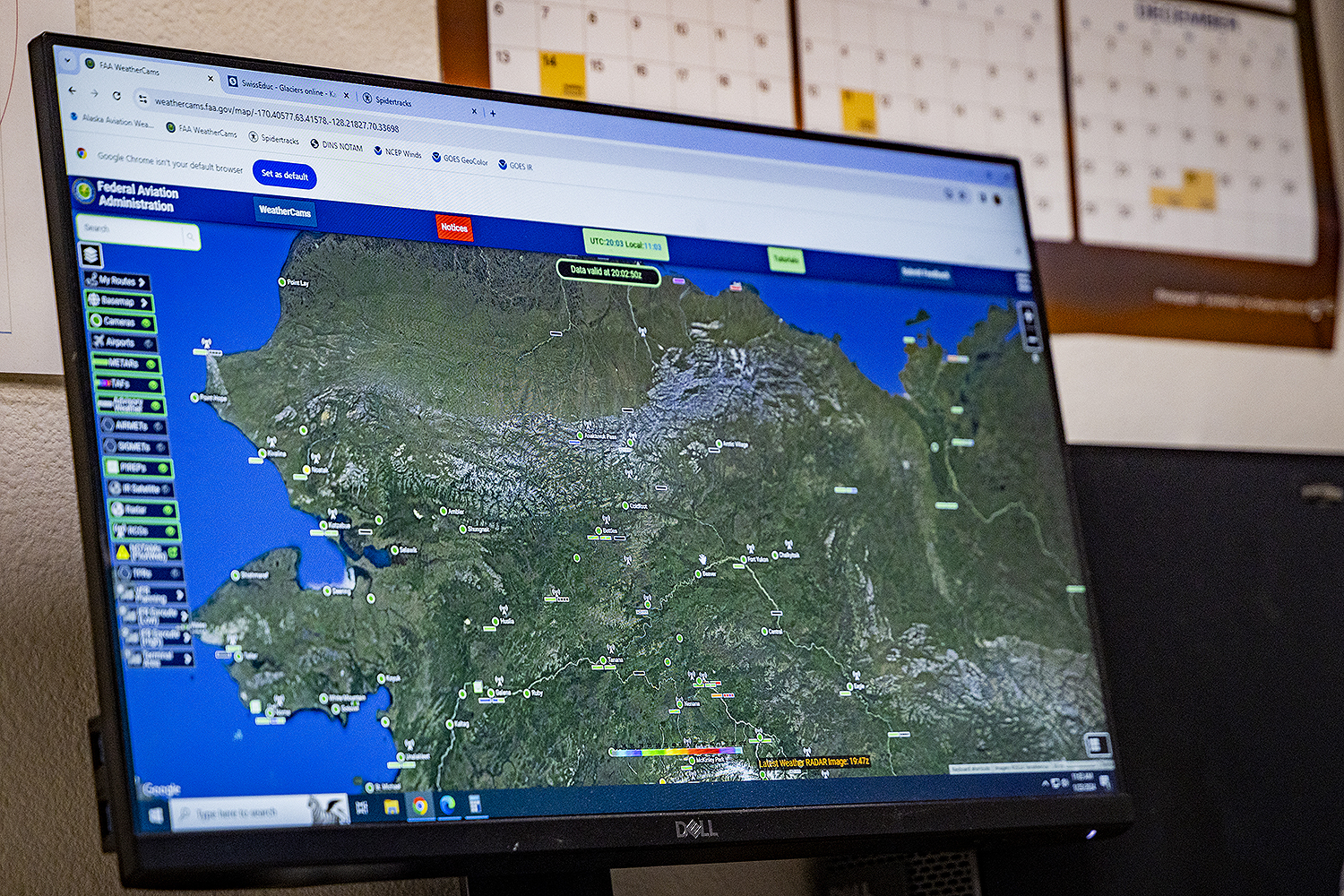

Green, Wright Air’s operations training manager, clicked a computer mouse to pull up the FAA website that hosts a map of the weather camera locations. He then clicked on the icon at Anaktuvuk Pass in the central Brooks Range to bring up four images showing the steep, snow-covered mountains surrounding the community.

He noted that the village airport’s automated weather reporting instruments, whose data appeared in a box below the images, reported haze with a visibility of 4 miles.

“So this is a good example,” he said. “We pull up the camera, now that it's actually starting to get light there, we can see that, realistically, it's actually much better than 4 miles.”

The automated weather instruments often have that kind of trouble estimating visibility accurately, Green said. The instruments cast a beam through a sample of air at the site and use a formula to extrapolate the results into a visibility estimate for the area. He noted that blowing snow, a small patch of fog or even road dust can skew the data.

“(Wildfire) smoke is a challenging one because the machine has trouble putting that information into a reliable visibility,” Green said. “The machine might say 5 miles, and you look at the camera and it might be realistically less than a mile visibility.”

Thunderstorms also confound automated stations, Green said. A station’s instruments

might “see” a clear, sunny afternoon while missing an enormous cloud just a few miles

away.

The automated weather stations report much more than visibility, though. They provide the temperature, atmospheric pressure, humidity, wind speed and direction, and the cloud ceiling height — all important information for pilots.

“It's a good tool, but the camera is really a great additional option,” Green said.

“We have the ability to compare and look at both pieces of information.”

Still, the cameras do have some limitations, he noted. Long dark days in winter curtail useful imagery. Also, internet and phone connections

aren't always reliable in Alaska's Bush, a problem that also afflicts the automated

weather stations.

A computer screen at Wright Air Service in Fairbanks displays an image of the weather at Anaktuvuk Pass at about 11 a.m. on Jan. 23, 2024.

Buckingham, the former UAF Ph.D. student, added two helpful features to the camera system when he built his prototype. The FAA has maintained both.

First, the website posts an aviation map of the area around each camera installation along with the images. On the map, diagrams show the field of view for each camera, allowing users to see exactly which direction it points.

Second, the system places the current weather images at each site side by side with a clear-day image. The heights and distances of nearby hills or mountains are marked on the clear-day image. That allows pilots to quickly compare it to current images to gauge the height and extent of any clouds.

So if a plane has already taken off from Fairbanks to head for Anaktuvuk Pass, for example, the pilot can radio for a camera report from a specialist at an FAA flight service station.

“(FAA) can look at the camera and say, ‘Well, we can see the mountain that's 5,800 feet, 5 miles away to the south,” Green said. “So the pilot, even en route before they get there, can at least get a little bit more of an assessment besides just the weather report.”

Pilots aren’t the only ones using the cameras for their jobs. National Weather Service employees also check the website regularly as they create forecasts for Alaska communities.

Jim Brader, a lead forecaster at the NWS office in UAF’s Akasofu Building, said he remembers meeting Buckingham when the former student was developing the camera system.

“He wanted to know, well, what are the useful things for us as forecasters,” Brader said. “We said visibility and ceiling height and stuff like that. And that was one of the things he did — having markers. A visibility marker, like a hilltop or a light, … and what the distance is. And the FAA has actually, to a large degree, replicated that.”

The NWS will create forecasts for runways around Alaska, and having the cameras often helps get a true picture of conditions, Brader said.

“There's times where you can have fog on one end and it's clear on the other,” he said. “The [automated] instruments, they pretty well represent right where the instrument is but not the entire runway. And having the webcams is a huge tool for that kind of stuff.”

“There were webcams around, of course, when he came up with the idea,” Brader said. “But pairing them at a runway … it’s something, I'm sure for pilots, that is used extensively, and we do too.”

Brader also praised a feature, added by the FAA, that allows the viewer to see a loop of images from the past six hours. The loop can tell a pilot whether a thunderstorm, fog or other weather is on its way in or out. The images also come at 10-minute intervals now, compared to the 30-minute intervals Buckingham started with.

A portable heater warms the engine of a Cessna Grand Caravan at Wright Air Service on the morning of Jan. 23, 2024, when the temperature was about minus 35 Fahrenheit.

A good place to return to

Buckingham didn’t know what he would do for a Ph.D. dissertation when he and his family arrived in Fairbanks — for the second time — in 1997. He was, by then, far from a traditional student.

Growing up in an Army family, Buckingham graduated in 1976 from an American high school in Germany. That’s about the time he earned his pilot’s license. He then attended the Massachusetts Institute of Technology on an Army scholarship, earning a bachelor’s degree in engineering in 1980.

A four-year commitment to the Army then turned into a 26-year career. After attending Army Ranger school, he married his wife, Martha, in 1981. They eventually had nine biological children and adopted seven more.

In 1988, he earned a master’s from Stanford University so he could teach engineering for a few years at the U.S. Military Academy in West Point, New York.

Army officers don’t rest in one place long, so, after a stint in Korea, he arrived at Alaska’s Fort Wainwright in July 1993. The family decided not to stay in base housing, though.

“We lived 20 miles out on Chena Hot Springs Road in a little house on No Name Lane, near what used to be Tack’s General Store,” Buckingham said. “We lived right next door to Rick Swenson, who was still running dogs in the Iditarod. That was our first introduction to Alaska, and we really loved it.

“We decided then and there that Alaska would be a good place to finish raising our kids some day, and it felt like God had led us there, and we would like to come back sometime,” he said.

In 1995, the Army sent them elsewhere for a few years. Then the West Point engineering department wanted him back; however, they said he needed a doctoral degree first.

Remembering Alaska fondly, Buckingham asked to get the degree in engineering management at UAF. West Point agreed, and so it was back to Fairbanks and the house on Chena Hot Springs Road in 1997.

Creating the vision

The next task was finding a doctoral dissertation topic.

“I remember specifically driving back from UAF one cold winter night in February 1998, … thinking about my course work, getting finished up and asking, ‘What am I going to do?’ Honestly, praying,” Buckingham said. “I started getting in mind that I should try something practical, because I was pretty good with practical hands-on stuff.”

Buckingham doesn’t remember exactly how he came upon the idea to create weather cameras.

“Somewhere in there, I think it may have been Tom George [’85] that suggested that the FAA in Anchorage had been doing some work with weather reporting in remote locations,” Buckingham said.

George, at the time, was a researcher and manager in the remote sensing group at the UAF Geophysical Institute. He was also a long-time local pilot. After leaving a 27-year career at UAF in 2000, he became the Alaska regional manager for the Aircraft Owners and Pilots Association, a national nonprofit group that advocates for noncommercial and recreational aviation interests.

“Tom or somebody, I can't remember who it was, just gave me the thought,” Buckingham said. “I do remember that I started thinking, ‘This sounds like something worth pursuing.’ Maybe I could figure out how to put some cameras in some remote villages and get that information back to pilots.”

Buckingham applied to the now-defunct Alaska Science and Technology Foundation and received $113,000 to fund the work. He bought about a dozen small cameras and some weather-proof enclosures for them.

“And I started piecing together how I could put a camera inside this little enclosure and then a modem that would enable me to dial up or call up that camera in a distant location and have it download the image and then upload it onto the internet,” he said.

He asked for help from the FAA, which operates the AWOS or “automated weather observing station” system, and the National Weather Service, which has the ASOS or “automated surface observing station” system.

A computer screen at Wright Air Service in Fairbanks displays a map of northern Alaska with icons marking the locations of the Federal Aviation Administration’s weather cameras.

“Each one of those AWOSs and ASOSs in those villages have a little enclosure, and it's got a little door you can go inside,” Buckingham said. “And when you get inside, it's at least warm … and it's got power.” And a phone line.

The agencies agreed to share the space and connections.

Buckingham searched for a few ideal automated station locations across central and western Alaska, flying himself in rented planes and on small air services that liked his project.

“After having gone to about 30 villages, I landed on three — Kaltag, Ruby and Anaktuvuk Pass,” he said.

Once he had the cameras up and connected, Buckingham spent about seven months operating and maintaining them. GCI donated 100,000 minutes of free telephone time that allowed him to call the modems in Kaltag, Ruby and Anaktuvuk Pass and download photos.

“I learned a lot of things in the process,” Buckingham said. “Like when a bad storm comes through, all of a sudden there's ice all over your enclosure lens and it can't see anything. Sometimes power was an issue. Sometimes the modems had to be reset.”

Buckingham eventually received a patent for the system. However, since he was working as an Army officer when he built the system, the patent was split with the U.S. government, so the FAA can use the design freely, he said. He receives no income from it.

After the system was done, West Point was calling, so Buckingham had to finish his dissertation and move on.

He met with the FAA regional administrator and some employees in Anchorage.

“I briefed the whole thing to them, told them what I had done, the money that I'd spent, where it came from, the images, and how it worked — and they were very happy with it,” he said.

So he turned the system, which he had dubbed FlightCam, over to the agency and left Alaska.

But he would be back.

Safety and efficency

Tom George, the former UAF researcher who may have given Buckingham the initial idea to develop the weather cameras, often flies from Fairbanks to Anchorage or beyond in his Cessna 185. He recalled being stopped by unexpected bad weather in Broad Pass in the days before aviation cameras.

Tom George.

“One of those times, I had to turn around, fly back to Fairbanks, get in my car and drive for 12 hours straight to get to Kenai, which is where I was trying to go that day,” he said.

Today, cameras cover much of the sky along the route.

“I've pretty much eliminated times when I had to turn around and come back,” he said. “I either can tell in advance, ‘Don't bother even trying.’ Or ‘Drink another cup of coffee and give it a couple hours.’ Or yeah, ‘Good to go.’”

Besides adding efficiency, the system improves safety, he said.

“It's fairly well known that once you take off to go somewhere, there's a tendency to want to try and make it, as opposed to turning around and coming back,” he said. “And that's where we often see a lot of accidents.”

A study of accident and flight statistics dramatically illustrates George’s points.

“Implementation of the weather camera service across the state of Alaska resulted in an 85% reduction in weather-related accidents and a 69% reduction in weather-related flight interruptions from 2007-2014,” the FAA reports on a website describing the current program.

Cohl Pope, the FAA’s weather camera program manager in Anchorage, said the figures came from a study conducted by the Mitre Corp. during the 2007-2014 implementation effort.

Pope, who started as a technician in 2002 and became program manager two years ago, said it's no mystery why the safety improvements were so dramatic following the expansion of the camera system.

“Within Alaska, several of the areas where we install weather cameras had no other previous weather information. Pilots were flying out to take a look at the weather versus having the information in their hands prior to takeoff,” he said.

The FAA's solar-powered Minx Islands weather station, which hosts an aviation camera, sits on a rocky beach on Thorne Arm east of Ketchikan.

Given the success in Alaska, the FAA Weather Camera Program recently received approval to expand the system by 160 new sites in Alaska and the contiguous U.S. during the next seven years, Pope said. The program will continue to be run out of the Anchorage office.

Some existing weather camera site locations in the Lower 48 already are available to the public on the website. Those sites are owned by other entities such as state transportation departments but are hosted by the FAA, Pope said.

Benefiting people

Jim Buckingham returned to Alaska in 2003. That’s when he left West Point to take a position as the inspector general for the U.S. Army in Alaska. In 2006, he retired from the Army as a lieutenant colonel.

Jim Buckingham stands next to his Piper Aztec at the runway in Napakiak. In the background is the automated weather station on which is mounted a set of internet-linked cameras similar to those that Buckingham pioneered in rural Alaska more than 25 years ago.

Those who follow Alaska news may remember the Buckinghams for their role in the highly publicized criminal case against McCarthy resident Robert Hale, better known as Papa Pilgrim. The Buckinghams took Hale’s children into their Palmer home after his 2005 arrest and eventually adopted four of them.

The Buckinghams also became involved in missionary work in the Yukon-Kuskokwim Delta. One of the Hale family members has a home in Napakiak, where Buckingham, his wife and three adopted children (not Hale kin) are house-sitting this winter.

So when Buckingham flies his Piper Aztec to and from the village, he consults the weather camera system that his efforts helped create.

In the Jan. 12 phone interview from Napakiak, Buckingham recalled the pressure he felt, as a Ph.D. student, to come up with that system. After all, a doctoral dissertation is supposed to create new knowledge.

But driving home from UAF that cold February night in 1998, Buckingham said, he also thought about how the Bible’s Book of Ecclesiastes asserts that there is “nothing new under the sun.”

“And I just prayed,” he said. “I personally credit God for lots of ideas that I think would have been hard in coming to me at the time — to bring this together and to make it work, and especially the follow-on, to have it be so beneficial.”