Sorrow’s Delicacy

Matthew Meduri

- African American Spiritual

I learned the mourning dove’s song at a young age.

My family had moved from a two-bedroom Cape Cod on a quarter lot in a residential neighborhood to a five-bedroom bilevel home on two and a half acres in the township when I was six. Although it might not have seemed like a big move, only a ten-minute drive, the difference in landscape was night and day. We traded concrete sidewalks and driveways, neighbors in homes that were only feet apart, and a few clustered deciduous trees for the combination of rolling farmland, marsh, woodlands, and neighbors that were hundreds of feet apart, each house equipped with a long limestone gravel driveway. Sure, we saw birds at our feeders, but unlike in the city where only a handful of backyard birds would occupy an area at a time, we had dozens upon dozens. It wasn’t unusual to see fifty Canada geese grazing on the grass in our backyard, a dozen deer nibbling at the wild blackberries at the edge of our property, hawks soaring through the sky with small rodents clasped in their talons, or the coyotes howling at night.

There was a pair of mourning doves, maybe more, in our front yard, either perched on the electrical wires or wattling around on the walkway picking at seed my mother offered them—she was always so aware of what others needed or might have wanted. She would point out their coo, a distinct set of usually four notes: ooOOO-oo-oo-oo. That first note beginning low and quickly rising, so loud and higher than the others—we never confused it for an owl’s monotoned hoot.

Maybe the sound of their coo gave me the notion that mourning doves were emotional birds. Maybe it was their appearance: gray, drab, and delicate with those big brown eyes—they’d shuffle around like they were lost or helpless. Caught in their soul-piercing gaze, I’d get the feeling that all of life hung heavy on them. I also believed their characteristic coo only manifested when something grave had happened.

I don’t remember who told me—it would have likely been my mother—mourning doves grieved, making that sad, elongated sound when they lost their mate. Whether perched on a telephone wire, pacing back and forth on the sidewalk, or standing, even kind of hovering, next to the body of their lost love, they sang a funeral dirge for the deceased. For most of my life, I believed I could relate to a bird that felt so deeply it would sing its song regardless of an audience. Regardless of the circumstances or the experience, they knew the burden of existence.

Namesake

MOURNING DOVE

Common synonyms: Turtle Dove; Carolina Dove; Carolina Pigeon; Carolina Turtle Dove; Turtle of Carolina; Tortola; Tourterelle triste; Paloma huilota; Long-tail’d dove; Coocoo dove; Moaning dove; Rain dove; Upland dove; Medicine bird

pigeon, noun

- Any of numerous wild birds of the family Columbidae, typically having a stout, stocky

body, short legs, a small head and bill, and a cooing voice, and feeding on grain

or fruit. Usually with distinguishing word.

- Pigeons are generally larger and more robust than doves, but many species have been given both names.

From late Middle English; from Old French pijon, denoting a young bird, especially a young dove, from an alteration of late Latin pipio(n- ), “young cheeping bird”; from classical Latin pipire “to peep, chirp,” of imitative origin.

dove, noun

- A stocky seed- or fruit-eating bird with a small head, short legs, and a cooing voice.

- Doves are generally smaller and more delicate than pigeons, but many kinds have been given both names.

From early Middle English douve; from Old English dufe; from Old Norse dufa, perhaps related to words for “dive,” because of the bird’s swimming motion in flight.

turtle, noun (archaic)

- Turtledove

From Old English turtle, dissimilation of Latin turtur, a reduplicated form imitative of the bird’s coo, of onomatopoeic origin.

Uilotl. Nahua

Turtur Indicus. Aldrovandi, Orn., 1599—Willughby, Orn., 1678

Guledisgonihi. Cherokee

Turtur carolinensis. Catesby, Nat., 1731— Brisson, Orn. 1760

Columba macroura. Edwards, Nat. His.1743—Linnaeus, Sys. Nat., 1758 (conflation)

Columba carolinensis. Linnaeus, Sys. Nat., 1758—Wilson, Am. Orn., 1810— Nuttall, Man., 1828— Audubon, Orn. Bio., 1831

Ectopistes carolinensis. Swainson, Zoo. Jour. 1827

uarawit-kschuka/warawit. Mandan

Zenaidura carolinensis. Bonaparte, Consp. Avi., 1854

Zenaidura macroura. Wetmore, 1931 Zenaida macroura. Olson et. al, 1990

In the Old World, you were known for your voice. You would peep, chirp, and coo, and they identified you by means of their dominant language, lingual interpretations of your vocalization. They transformed you into symbols of peace, tenderness, sexuality, and love. You were all the same. In the New World, they heard your voice and named you in an attempt to comprehend your sounds, your nature. The Cherokee heard guledisgonihi when you called, which meant “it cries for acorns.” The Nahua people gave you the name uilotl because you constantly wept for your lost mate. Uilo-o-o was your song.

As they hunted you, ate you, stuffed you, and studied you, they sought further to identify you. Your name was revisionist poetry, an attempt to reduce you to your essence. Pigeon. Dove. Turtle. You flew here; they found you there. You weren’t lost like a crying child alone in a grocery store—you knew your way. They named you for your location, your appearance, your diet, for the love of their life. No matter how convoluted your name became, your voice was always heard. That distinct coo that stirs its listeners’ emotions. The sound fills them with sorrow, fear, comfort, or longing. Maybe your voice cries for humanity, for the atrocities they commit to the world, to one another, to you, mourning dove.

Field Guide Description: Typical Bird

Given the mourning dove’s plump shape and silky, soft-gray plumage, you can easily identify it as a member of the pigeon family. It struts around with a certain delicate but determined swagger, comically bobbing its bulbous head in sync with each step of its pale red legs, forcing itself forward with momentum, stopping to poke the ground for seeds with a dark, slender beak. Like the feral pigeon, it’s a voracious eater, but unlike its city-dwelling, trash-eating relative who is unphased by the presence of pedestrians, flying in and around traffic and buildings, mourning doves are fairly skittish in the presence of humans.

If you can get close enough without startling the bird, you’ll notice its more defining characteristics. It has dusky, light gray feathers with black spots on its wings and a crescent-shaped patch of dark feathers below the eyes that are outlined by pale blue skin like heavy eye shadow. The long, tapered tail, which distinguishes it from most other North American doves, possesses outer feathers that are black-bordered and white-tipped. Although some describe their color as dull, their feathers possess a beautiful iridescence, especially in the males: a bluish cap and nape, a rosy hue to their chest, and a slight purplish tinge.

Hunting Season: Opening Day

Welcome, Dove Hunters! It’s that time of year again to feed your passion with the ultimate outdoor experience. We have an exciting Labor Day planned at [fill in the blank] Plantation. Dove hunting is a time-honored Southern tradition where generations of our kin gather for food, fun, fellowship, and fowl shooting.

Start the day with a hearty Southern breakfast to power you and your family through the day. You’ll need the energy because those little buggers are fast, flying 30-55 mph, and a wing shot is tricky. Be sure to wear your best camo, have your shotguns loaded, and your coolers stocked full of ice water, Coke, and beer. Don’t forget to stop by the clubhouse for your complimentary sack of boiled peanuts. Nothing says Southern tradition like snacking on those delicious morsels through a cacophony of gunshots and dove cries on a humid, ninety-degree day.

At [fill in the blank] Plantation, we diligently work year-round to prepare our fields with only the finest sunflower, millet, corn, and wheat to attract loads of birds. We do everything in our power to ensure that birds are plentiful. If we don’t have doves, then nobody does.

In the field, there’s nothing quite like the rush of doves flying left and right while fellow hunters shout, “Over you! Over you!” For some, this may be their first experience on a dove field. For others, this may be the time to work on your rusty shotgun shooting between sips of beer. Either way, we want to make it memorable. That is why we let you do all the hunting while we do all the cooking. We start the smokers at seven in the morning, so we have a big Southern dinner ready when you come back from the field. How does barbeque with all the sides and fixin’s sound? Add some live music and a bonfire for the perfect day. Too good to be true, right? This really is a social affair, folks.

[fill in the blank] Plantation prides itself on its family values, Southern heritage and hospitality, and offering the finest dove hunting this side of the Mason-Dixon. Our hope is that when the day is done, there’ll be plenty of stories to tell about who shot the most, who had the best shot, and who didn’t shoot a thing. The family roots run deep at [fill in the blank] Plantation, and our staff is here to provide hunters with an outdoor paradise, delicious home-style meals, and exceptional accommodations. Here they come!

Foodways: The South

Roasted Doves

Or

Dove Pie with Vegetables

I was born in Thomas County Georgia, on the Springhill Plantation. My parents worked for both owners, Daddy as a handyman, and Mother as a cook. I quit school when I was fifteen years old, to help my mother in the kitchen. I worked with her for four years, learning many of her original cooking secrets and those that she passed on to me from my grandmother.

[At the Horseshoe Plantation] it became my duty to cook, open and close the house for hunting season. The first season, one night after dinner, [the owner] Mr. Baker asked me to come into the dining room where he and his brother-in-law sat at the table. He told me that he wanted me to know that the food was the best he had ever had since he had been coming South.

My years at the Horseshoe Plantation were rewarding and exciting. It was rewarding to have my cooking appreciated as it was by members of the Baker family and their friends. And it was exciting to have some mighty famous people enjoy my plain and fancy menus and recipes.

(Flora Mae Hunter, Born in the Kitchen, 1979)

Folklore: An Anecdote

William Faulkner used to dove hunt. One time he tried to get his housekeeper to prepare and cook the mourning doves he’d bagged, but she refused on the account that she believed they carried people’s souls to heaven. Another time he went on a dove hunt in Los Angeles with director Howard Hawks and Clark Gable, but, apparently, that was a different type of expedition.

Field Guide Description: Nesting

Many lists of mourning dove facts often have the entry “mates for life.” This skewed fact plays into the sentiment of doves as symbols of love or archetypes for monogamy. Where many numbered lists of curated information annoy me at the very least, mostly because the information has not been thoroughly vetted or an objectivity bias exists, I’m highly skeptical of “facts” that impose morality or human characteristics on animals as though we can sit back and say, “well, if the animals can do it, why can’t we?” Perhaps my skepticism (cynicism, maybe?) comes from my failed first marriage and my propensity to forego all forms of idealism, despite loving love. While mourning doves are indeed monogamous, meaning they will mate with the same bird during a nesting season, they don’t always dwell in lifelong matrimony.

During courtship, the male advertises himself with a perch coo. As the two form a pair bond, they display, what appears to be, different types of affection: allopreening, which consists of gentle caresses or nibbling concentrated at the head and neck, and billing, which consists of the female inserting her beak into the male’s open beak, and then the brief pumping of their heads. Copulation typically follows.

They build a flimsy nest of loosely arranged sticks and have an upward of five to six broods, usually two eggs per brood. Both parents incubate the eggs and rear and feed the fledglings. If either bird dies or deserts the nest during incubation, the remaining dove usually abandons the eggs within a few days. Once mating season is over, mourning doves may re-pair in subsequent seasons, but there is no guarantee. Pairs that have bred together in a previous season have a better chance of reproductive success than birds that search for a new love. But that isn’t always the case.

Hunting Season: Baiting

The first day of hunting season is when most baiting occurs, serving as a festive occasion for hunters to get reacquainted with one another and to make plans for later hunting excursions. One reason for baiting fields on opening day is that no one wants their first party of the season to flop, especially if it’s a pay hunt with the added pressure to guarantee birds. To avoid this problem, illegal baiting sometimes takes place.

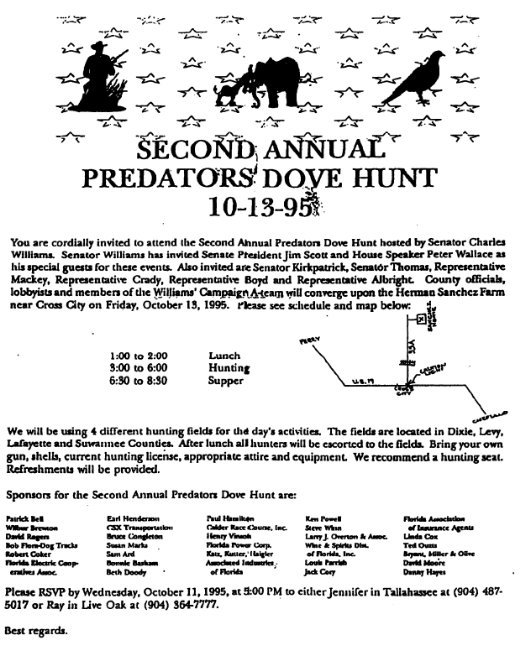

A high-profile opening day baiting bust in 1995 triggered a new wave of Congressional attacks on Federal regulations, leading to intense legislative scrutiny and an attempt to weaken the law. On that October day, USFWS special agents raided the second annual “Predators Dove Hunt”—a charity dove shoot and beer blast—in Dixie County, Florida. Officers found illegal bait everywhere and saw doves settling down in the fields despite all the blasting guns. As soon as the agents arrived to break up the hunt, most of the 150 hunters fled.

Agents seized nearly 500 bird carcasses, many of them non-game birds. In all, 86 hunters were cited for baiting and bag limit violations, and later paid nearly $40,000 in fines. One of the agents called it the most flagrant baiting case he’d worked in 24 years and a prime example of what bait does to birds. “It was a complete war,” he said. “Very effective baiting.”

Present at the Dixie County “hunt” that day were four Florida sheriffs, the regional director of the Florida Game and Fresh Water Fish Commission, state wildlife officers and a host of local politicians. These individuals contacted their Congressmen and so began a concerted effort to dismantle the baiting law.

Upon hearing of the “heavy hand” of Federal law enforcement agents, U.S. Representative Don Young (R-AK) introduced the Migratory Bird Treaty Reform Act to loosen baiting restrictions. As chairman of the House Committee on Resources, Young called a hearing and solicited testimony from angry hunters.

Not surprisingly, the episode was depicted as “a little Ruby Ridge” and the Federal agents involved were lambasted for “overzealousness” in enforcing the law. Even Brent Manning and Ron Vogel flew in to offer testimony on the need to “fix” baiting laws.

(Migratory Bird Treaty Reform Act of 1998, Hearing Before the Committee on Environment and Public Works, United States Senate, One Hundred Fifth Congress, Second Session on H.R. 2863, A Bill to Amend the Migratory Bird Treaty Act to Clarify Restrictions under that Act on Baiting, to Facilitate Acquisition of Migratory Bird Habitat, September 29, 1998)

Foodways: The South, II

Simple Grilled Doves

Lynn Rossetto Kasper: Why do you think it’s so hard for many of us to think about the hunting, the field dressing, and the cleaning of the animal? On one hand it’s logical: we’re detached from it. But on the other hand, man has been hunting since we first started to move. There’s so much violence now in our society, and yet there’s this disconnect from the idea of going out there to get our own food.

Jesse Griffiths: People associate hunting with gun culture, and I think hunting should be associated with food culture. A gun is a tool you can use to get food like the hoe you would use to turn the soil in your garden. I think people are pretty leery about starting to hunt because they feel the violence, which is inherent in the process, is something insurmountable.

It’s a difficult process. It can be emotional. I think if it’s not emotional for you, you shouldn’t do it. But I think we really want to convey the fact that this has been happening for a long time. It’s a good way to approach food. It makes you think about your food, in general, as a whole. I think if people experience it, if they know people who are experiencing it in the right way or they see it done from a different perspective, then they’re more likely to change their ideas about what hunting is, if they were opposed to it.

LRK: What is that emotional connection? You said if you don’t feel an emotional connection, it’s not right.

JG: If you’re taking the life of something, that’s a big deal, and it has some weight to it. You should always feel it. If it’s a little dove or it’s a big deer, it’s the same as a life. That animal didn’t expect its day to end like that, and you are then required to treat that with the utmost respect. If you don’t feel that, then I think you’re missing the point.

That feeling translates into when you’re preparing things: you just put more thought into it, you’re required to. You just went through this long process of getting the gear together, the traveling, the physical exertion, the excitement of the actual hunt, the processing of the animal, the packaging, and making sausage. There’s so much work involved, it just makes you feel and understand food at a base level.

LRK: Is there a favorite way you have for cooking a game bird? I’m thinking of something small like dove.

JG: I just love grilled doves—salt, pepper, olive oil and a hot grill. That’s more because I associate that with the night of a hunt and we’re all around a fire, grilling our doves—that’s a lot of it too. A good meal is a lot more than just the food.

(August 29, 2013, The Splendid Table)

Folklore: Origin Stories

I. Mandan

A flood had covered the earth. The Mandan people had spent many days in a large canoe traveling across the water. When a mourning dove flew to them, bringing a fresh willow branch, they saw this as a sign of land. Soon, the people arrived on the shore where the bird taught them how to build lodges, hunt, and gather fruit. In honor of the bird that showed them how to hunt, they performed the Okipa, or the buffalo calling ceremony. The ceremony did not begin until the willow was fully grown on the banks of the Missouri River. The willows are sacred as they hold the flood waters at bay. Mourning doves are also sacred and should not be harmed.

II. Wyandot/Huron

There was once a young girl who loved and cared for a flock of white doves. The doves fluttered around her, perched on her, clinging to her clothing. She would talk to them and hold them in her hands. They came to adore her. One day, she became sick and died. As her spirit traveled across the land to the enter the afterlife, the doves followed and tried to gain entrance alongside her. Sky Woman, the deity who guards this entrance, allowed the girl’s spirit to come in but refused the doves’ entry. They did not leave but perched on trees outside the entrance and waited. Sky Woman brought forth smoke to force the doves to leave and told them they would never again sing anything but a mournful song. The smoke singed and stained their feathers a light gray, and they left, forever singing the loss of their beloved companion.

Field Guide Description: Vocalization

As in many other pigeons and doves, main vocalizations have sexual context, and development is related to sexual maturity. Uttered repeatedly by unmated males in breeding conditions, often, but not always, from conspicuous perches. The principal function seems to be an attraction of a mate. Females sometimes utter faint perch coos. Unpaired males devote considerable time to perch cooing and other displays. The perch coo is technically the mourning dove’s song.

(Thomas S. Baskett, Ecology and Management of the Mourning Dove, 1993)

* * *

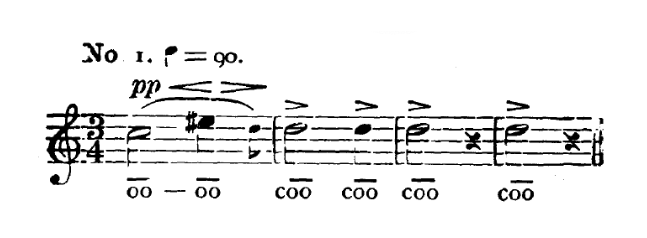

The perch coo of this species is the well-known strain, the plaintive sound of which has given to the bird the name of “Mourning” Dove. This strain impresses one as most beautifully melodious. It consists of a series of three (sometimes four) notes on one pitch, preceded by an introductory note which begins below the sustained pitch, glides up above it, and then down to it, thus (No. 1):

(Wallace Craig, Emotion in the Mourning Dove, 1911)

Cucurrucucú Paloma

In 1954, Mexican composer Tomás Méndez Sosa wrote a song that began as a traditional huapango, a style of Mexican folk music composed using fast rhythms, an ensemble of three stringed instruments, and falsetto vocals. Méndez, self-taught and influenced by nature, birds, the countryside, and people’s domestic lives, wrote some of his earliest compositions as a boy, laying in a field, by recreating the sounds of the wind in the trees and birds’ songs. The song’s title is an onomatopoeic reference to the mourning dove’s call, and the lyrics describe the misery, grief, and longing of a man whose lover has left and is visited by a dove that sings to console his pain. Many have performed this song, including Lola Beltran, Harry Belafonte, Joan Baez, and Silvia Perez Cruz, and various iterations have appeared in several films.

In Pedro Almodovar’s 2002 film Talk to Her, Brazilian singer Caetano Veloso transforms this traditional mariachi ballad into a desperate portrayal of loss. Accompanied by guitar and cello, Caetano’s soul-piercing falsetto (at times mimicking the dove’s coo) with touches of Portuguese fado compels the listener to ponder the longing in the melody and lyrics as one might with the sound of the mourning dove. There is a deep existential sorrow that exists even on a summer night, poolside at a party with cocktails and friends.

Hunting Season: Afterschool Special

COLUMBIA, S.C. (AP) – “Shoot for the Future—Don’t Use Drugs,” a slogan the state wildlife department is using to encourage youths to shoot doves instead of using drugs, was denounced by animal rights organizations. “We are outraged of the absurdity of giving people two choices—shooting doves or shooting drugs,” said Heidi Prescott, a national director of the Fund for Animals. The group, based in Silver Spring, Md., claims 250,000 members. Dove shoots began a year ago to give parents and children a chance to enjoy the outdoors, said Brock Conrad, director of the state Division of Wildlife and Freshwater Fisheries. This year’s slogan was patterned after “Hooked on Fishing, Not on Drugs” program in South Carolina and other states, he said. The Fund for Animals will join the Animal Rights Alliance of South Carolina and the Greenville-based Peaceable Kingdom to protest the hunt in three counties Sept. 7. Protestors also plan to be on the dove fields the next day for the hunt, a South

Carolina tradition. “A lot of these animal rights groups they think that rats and pigs and dogs have the same rights as children, so it’s just kind of hard to reason with these groups,” Conrad said. Biologist Skip Still said the hunt in each county is limited to 35 adults who must bring no more than two children under 15 years old. “What we want is to give the children the experience of the hunt and then they can make an educated decision about hunting,” Still said. Sue Farinato, president of the 300-member Peaceable Kingdom, said the hunt is “clearly stating that violence is alright, but drugs aren’t. Drugs have always been surrounded by violence.” The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service estimates there will be 475 million doves at the opening of the fall season. About 9 percent are killed by hunters and many others die from natural causes. Because doves have a high reproductive rate, they will replenish their population by next fall, Conrad said.

(September 4, 1991)

Foodways: Haute Cuisine

“The flesh of these birds is remarkably fine, when they are obtained young and in the proper season. Such birds become extremely fat, are tender and juicy, and in flavour equal in the estimation of some of my friends, as well as in my own, to that of the Snipe or even the Woodcock; but as taste in such matters depends much on circumstances, and perhaps on the whim of individuals, I would advise you, reader, to try for yourself. . . When caught in traps and cooped, they feed freely, and soon become fat, when they are excellent for the table.”

—John James Audubon, “Carolina Turtle Dove,” Ornithological Biography

Game cuisine is not a new phenomenon, despite what the hunter-chefs of the 21st century may claim. Such movements as farm-to-table, field-to-table, field-to-fork, field-to-plate, slay-to-gourmet, or any other here-to-there quip aims to redirect consumers from Big Ag produce and meat to either buying locally farmed food or simply growing and hunting their own. These hunter-chefs, whether self-taught or formally trained, offer up anecdotes of their hunting expeditions and cookbooks for how to masterfully kill, clean, and execute a delicious meal of wild game. Although presumably well-intentioned, they all spout the same clichéd rhetoric: greater connection to the land and animals, pride in self-sufficiency and food traceability, and ad nauseam comparisons to pioneers. Their mostly banal insight and observations can make one’s eyes glaze over, but their recipes are sometimes fascinating. But not everyone is capable of shooting and cleaning wild fowl and then serving up an Old World French dish such as the game bird confection Chartreuse like chef Daniel Boulud. Elevating wild game cuisine is anything but a new food trend.

* * *

Wild game is such an ingrained part of American cuisine that one could open almost any American cookbook from Amelia Simmons’s American Cookery to Irma S. Rombauer’s Joy of Cooking to Edna Lewis’s The Taste of Country Cooking to Sean Brock’s Heritage and find at least one recipe for game birds. Yet, some of the most creative recipes aren’t necessarily found in gourmet cookbooks but rather in self-published recipes and the compilations released by State Natural Resource Agencies and Wildlife Divisions. Just regular people trying to keep things interesting.

* * *

George Leonard Herter’s Bull Cook gives an account of Wyatt Earp’s renowned culinary skill in the Old West. Supposedly, after his first wife died, his new passion became food. In Dodge City, Kansas, he cooked a mean pickled buffalo tongue, and his breakfast of buffalo, a ribeye steak with onions atop buttered toast, and two eggs was a robust start to any buckaroo’s day. When Earp moved to Tombstone, Arizona, he ran the Oriental Saloon, a place known for its liquor, gambling, bloodshed, and, apparently, food. Earp was a dove hunter and even recalled his best shot being when he “killed nine mourning doves out of a flock coming into a water hole with one shot.” He had a particular way of cooking doves, too. He browned the spatchcocked birds in butter and suet and then tossed them into a large pot to simmer with water, cabbage, carrots, lima beans, onions, and sage. He removed the cooked doves and served them with brown rice, potatoes, and the stewed vegetables. This is all true, despite the lack of sourced material and quotations in Herter’s book.

* * *

Until recently, I had never viewed mourning doves as a menu item. The thought never crossed my mind. Perhaps, it was my lack of knowledge about game birds, the difficulty of separating the emotional connection I have to this bird, or that, regionally, dove hunting is less celebrated in the Midwest than it is in the South and Southwest. I don’t hunt and have never shot a gun up to this point in my life—unless you count the bb gun I had as a kid that I aimed at birds with some of the worst accuracy imaginable. But my curiosity is piqued when considering the mourning dove as a gastronomic delicacy. The thought of dove hunting fills me with a despondency I can’t fully articulate, but I would gladly clean, prepare, and eat doves for a meal.

I admire dishes that use regional and seasonal flavors and ingredients of a specific place. I’ve read recipes where dove breasts or whole birds are served atop sautéed collards or wild greens like chicory, watercress, or purslane, cooked with fruits such as peaches, pears, cherries, blackberries, huckleberries, grapes, and prickly pear, topped with moles (distinctively Mexican) or red eye gravy (distinctively Southern), with a variety of seeds and nuts or wild mushrooms, and alongside wild rice, pilau, ancient grains, Carolina Gold rice, and sweet potato hash. Given the opportunity, I would cook and try them all.

Folklore: Rain Birds

Many Pueblo tribes of the American Southwest believed mourning doves were rain birds. Their song was a chant and an incantation to bring rain or to locate a water source. For this reason, the names in various Pueblo languages reflect the sound of the dove’s call: kaipia’o’one in Picuris, ko-oñwi in Tewa, ho-o-k’a in Keres, huwi in Hopi, ginamu in Jemez, and ni:shabak’o in Zuni. Among tribal mythology, there are tales of doves searching for water, praying and chanting for rainfall, venturing out to bring back rain for crops, or doves who mislead people to places without water. One Hopi tale departs from the rain bird belief and uses the mourning dove’s notes for personal distress. The story parallels the Hopi women who would cut their hands on the sharp edges of the dropseed plant while harvesting its grain:

A dove injures herself while gathering seed and moans, “hohoo ho, hohoo ho, hohoo ho, ho-ho-ho.” A coyote thinks he hears someone singing and approaches the dove to ask if she is singing. The dove replies, “I am not singing. I am crying.”

Namesake: Eponym for Love

“Zenaide lives! A proof of this is in the sweet Zenaida dove, Columba Zenaide Bonaparte. It is at all times so delightful to think that a thousand years from now this mark of my esteem and of my tenderness will live on with this lovely species. I take this occasion to make known to the world that it is in your honor that I have bestowed this name. At this moment I can only love you on paper—what truly interests me in the world is you.”

—Charles Lucien Bonaparte to Zénaïde Bonaparte, undated letter

Her marriage to him was, unfortunately, a mere footnote, though she bore him twelve children and shelved her own passions for his. On June 29, 1822, Zénaïde Bonaparte married her cousin Charles Lucien Bonaparte, an arrangement made by their fathers to carry on the Napoleonic succession. They were young, eager, and full of affection, though they had only first met on their wedding day. The two looked more like siblings than lovers. They traveled from Europe to America to stay at her father’s estate in New Jersey, Zénaïde pregnant with their first child, Charles ambitious to begin his career in the natural sciences. With his interest in birds and language, Charles set out to revise Alexander Wilson’s American Ornithology. He was often in either Philadelphia or England for work, leaving Zénaïde alone to raise the children, though he wrote her often.

Later in life though, Zénaïde believed Charles’s words to be nothing but an empty gesture. He had grown into a workaholic, a gambler, and a political fanatic, spending long trips away accruing large debts and being active in protests, even riots, in Italy. The two became estranged for the last few years of their lives, Charles not seeing his children and begging for a reunion. Despite his best efforts—letters, visits, and sending pleading relatives to intervene—he could not win back his wife’s affection. In the spring of 1854, she received an imperial decree to officially end their marriage, though she died only a few months later from diphtheria.

Field Guide Description: Nesting, II

In my neighbor’s cherry tree is a nest of loose twigs. As I pass under the tree, I often look at that long-abandoned nest and think what a perfect place for a couple of mourning doves. I wonder if the previous occupants either died or divorced, raised many broods or were eggless. Unfortunately, there are no public records to satisfy my curiosity—no marriage license, divorce decrees, titles for property, or birth certificates.

Hunting Season: [White] Conservation

“Whenever the people of a particular race make a specialty of some particular type of wrong-doing, anyone who pointedly rebukes the faulty members of that race is immediately accused of ‘race prejudice.’ On account of the facts I am now setting forth about the doings of Italian and negro bird-killers, I expect to be accused along that line. If I am, I shall strenuously deny the charge. The facts speak for themselves.”

—William Temple Hornaday, Our Vanishing Wildlife

Just before the passing of the Migratory Bird Treaty Act of 1918, which protected nearly 1,100 species of migratory birds and designated specific hunting seasons and bag limits for game birds, William Temple Hornaday wrote the book Our Vanishing Wildlife in 1913, which coincidentally was the same year my grandfather emigrated from Reggio Calabria to New York City. Hornaday was a long-time hunter and taxidermist who wrote a book described as a riveting call to action against the destructive forces of overhunting that wiped out the passenger pigeon.

Although the book addresses many wildlife issues, what I find curious about this book, specifically, are the two chapters directed towards three distinct groups of people. The chapter entitled “The Destruction of Song-Birds by Southern Negroes and Poor Whites” describes his disgust for African Americans and lower-class white Americans who hunt mourning doves for food. To Hornaday, “the killing of doves represents . . . a decline in the ethics of sportsmanship” and is a hobby for “poor white trash” and African Americans who “belong to a primitive race of people.” This sounds like more than a bird issue for this guy.

A chapter preceding this one entitled “The Slaughter of Song-Birds by Italians” describes how Italian immigrants would kill songbirds for food, which was and still is a fairly common practice and culinary delicacy in Italy. Even as unusual as that may seem, songbirds were regularly eaten by all before the 20th century. All one needs to do is look at a few dozen restaurant and hotel menus or cookbooks from the 1800s for clarification.

The aim of these two chapters was not to reprimand the practice of dove and songbird hunting but was an attempt to disparage and further demonize people who were the main subjects of scorn, prejudice, and violence at that time. He’s more concerned with furthering the narrative that “these people,” including American Indians, were vile scapegoats on which more affluent, Anglo-Americans could place the blame for the barbaric destruction of our North American wildlife.

In reality, most of this destruction and overhunting was a byproduct of the government, society, and [white] people of that time he wishes to praise, a kind of white supremacy amnesia. But he doesn’t stop at that. Hornaday advocates for restricting Italians’ rights in every state because they “are pouring into America in a steady stream. They are strong, prolific, persistent and of tireless energy. . . They work while the native Americans sleep. Wherever they settle, their tendency is to root out the native American and take his place and his income. . . The Italians are spreading, spreading, spreading.” It’s hard for me not to see this as a personal affront to immigrants like my grandfather who came to this country young and poor and doing whatever they could to assimilate into the culture, oftentimes, shedding their own cultural customs, language, heritage, and even names just to belong. This hysterical, white guy paranoia is a tune we continue to hear in America remixed with each new ethnic scare.

Another instance that negates his “non-racism” claim is when he, with the help of the infamous eugenicist and his best friend Madison Grant, placed Ota Benga, a living pygmy native from the Congo, on display in the monkey house at the Bronx Zoo in 1906. Consequently, years later, when Benga could not return home to the Congo, he committed suicide. So much for conservation.

Foodways: Indian Nations

Roast Dove with Black Walnut, White Sage, and Adobe Bread Stuffing

Or

Stuffed Dove with Sautéed Purslane

Native Americans have lived on this land since before history’s written records. The story of the people in the Southwest and the story of this place is one story. One cannot think of this place and not think of its people. Indigenous people of the Southwest are as diverse as the land they live on. Nevertheless, they share the belief that food is important beyond physical sustenance. The acts of hunting, growing, gathering, cooking, and eating take on a spiritual aspect akin to prayer. The relationship between the land and its people is sacred.

What makes Native food traditions unique is the respect for the bounty enjoyed by the people. Among many Native peoples of the Southwest, nothing is taken for granted. Offerings are made to corn plants, often in the form of a song and prayer. These songs and offerings are believed to help the plants grow and be productive.

Animals are honored, too, through dances and in ceremonies. Native American hunts are never done for sport, but rather game is hunted for its meat and skins. This respect for the natural balance of things is basic to Native American belief.

Life is still going on; our culture and our food ways are not dead. They live inside each of us. Every time we prepare food as our elders did, we carry on these traditions. We need to listen to our elders, and learn as much as we can, so that we pass these ways onto our own children and share them with other people outside our own communities as well.

(Lois Ellen Frank, Foods of the Southwest Indian Nations, 2002)

Folklore: A Symbol

The mourning dove became the official symbol of peace for Wisconsin in 1971 and the official state bird of peace for Michigan in 1998. There is still the notion that all doves are the pure, white doves of Old World symbols: the dove that promised dry land to Noah or that landed on Christ’s shoulder after his baptism. The mourning dove, however, is a symbol of sorrow. Its haunting sound may evoke deep, unexplainable, and, oftentimes, visceral feelings of distress or despair. Countless films have used the mourning dove’s coo, typically old Westerns and Horror, to create a kind of melancholy ambiance, the verisimilitude of place, or an auditory device for foreshadowing.

Alexander Wilson’s 1812 description of the mourning dove’s vocalization was one of anthropomorphizing and poetry:

The hopeless wo of settled sorrow, swelling the heart of female innocence itself, could not assume tones more sad, more tender and affecting. Its notes are four; the first is somewhat the highest, and preparatory, seeming to be uttered with an inspiration of the breath, as if the afflicted creature were just recovering its voice from the last convulsive sobs of distress; this is followed by three long, deep, and mournful moanings, that no person of sensibility can listen to without sympathy. A pause of a few minutes ensues, and again the solemn voice of sorrow is renewed as before.

As a lonely, overworked, and impoverished immigrant, someone who often suffered from severe depression, he understood sorrow well. The mourning dove’s gentle voice, when heard at dawn while all is still and quiet and hopeful, could be why so many feel a sense of peace rather than the dull ache of sadness. Still, there is a strange feeling that exists at dusk with each echo of the bird’s coo, the combination of calm stillness and a sense of foreboding. The call for a mate, the sound of life’s temporality, the feeling of one’s mortality.

Matthew Meduri is a writer and educator living in Kent, Ohio. His writing has appeared or is forthcoming in Gastronomica, Litro, Story, and two anthologies. He holds an MFA in creative writing from the Northeast Ohio Master of Fine Arts (NEOMFA) consortium and is the recipient of a 2022 Individual Excellence Award from the Ohio Arts Council.