Don't Plant a Problem: Invasive Garden Species

FGV-00146 View this publication in PDF form to print or download.

Sometimes garden plants jump the fence and invade natural areas. Plants become invasive when they threaten wild areas by displacing native vegetation and destroying wildlife habitat. Many of the major problems caused by invasives in other states have not yet been experienced in Alaska. By not planting known invasive species, gardeners can help stop them from spreading in Alaska.

To help guide gardeners in making decisions about what to grow in the garden, the Cooperative Extension Service has developed the following “DON’T Plant in Alaska” list. Plants have been put on the list for a number of reasons. Some have escaped in other states and are known to grow well in parts of Alaska. Some are classified as noxious weeds. Some have a reputation for being aggressive in the garden. Others may belong to a genus of notoriously problematic plants.

Some plants are weedy but don’t survive outside of cultivation. An invasive plant goes beyond aggressiveness in the garden. These plants have the ability to strong-arm other species into surrendering their place in the wild. The term ‘noxious’ can be used to describe some of these species, but noxious is also a legal term. States have noxious weed laws, to protect agriculture and the public interest. Alaska has 12 species on its noxious weed list and another eight that are considered restricted noxious weeds.

Because of Alaska’s broad climatological differences, plants that are invasive in one part of the state may not be troublesome elsewhere. In addition to those species that Extension suggests not planting in Alaska, an additional five have been added to the “DON’T Plant in Southeast Alaska” list. As our understanding grows, this list may change.

DON’T Plant in Alaska

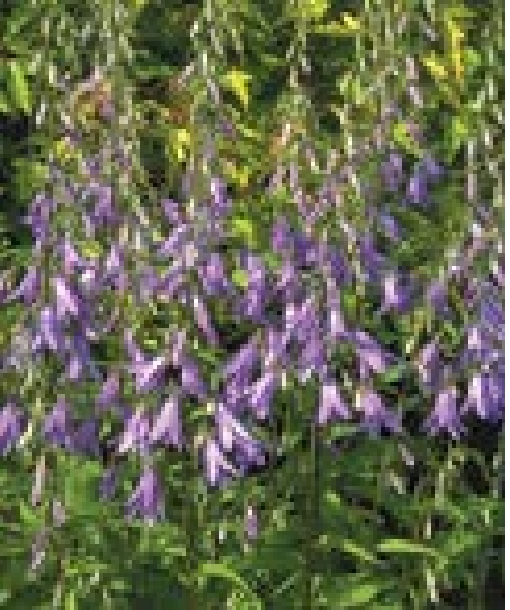

Rampion bellflower (Chimney bells), Campanula rapunculoides

Rampion bellflower (Chimney bells), Campanula rapunculoides

Becoming extremely aggressive wherever it is planted, rampion bellflower is known by some gardeners as the “purple monster.” It produces a large number of seeds and also spreads by creeping rootstocks. It escapes into lawns and can persist with frequent mowing. Removal by digging is usually not successful because plants resprout from any small pieces left in the ground.

There are many non-invasive species of Campanula which can be planted as alternatives. Campanula persicifolia, the peach-leaved bellflower and C. lactiflora, the milky bellflower are two which don’t spread to unwanted locations. The milky bellflower is not as winter hardy as peach-leaved bellflower. Campanula rapunculoides should not be confused with Adenophora, although both are often called ladybells.

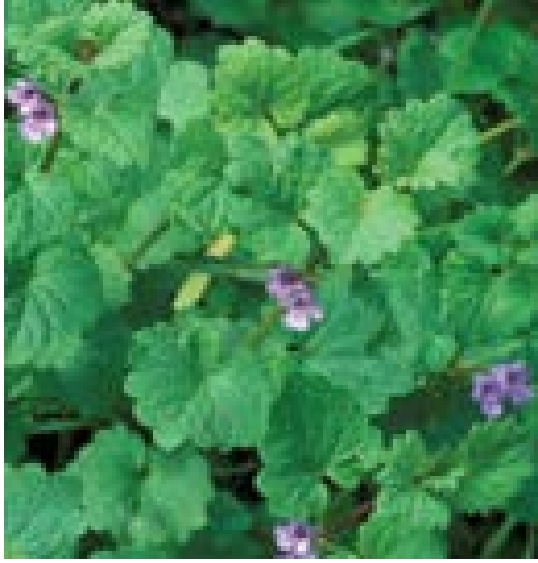

Creeping Charlie (Ground ivy), Glechoma hederacea

Creeping Charlie (Ground ivy), Glechoma hederacea

In many parts of United States creeping Charlie is considered a weed and is not offered for sale by nurseries. In Alaska, it is most commonly sold in hanging baskets because of its long, trailing stems. As a groundcover, creeping Charlie roots at every node and quickly takes over. It has escaped or naturalized in 46 states including Alaska where it can be found spreading in wooded areas in Southcentral.

It is difficult to suggest an alternative groundcover to creeping Charlie because all groundcovers spread and could potentially get out of hand. A couple of less invasive ideas include bugleweed, Ajuga reptans, which is not always hardy in Southcentral and yellow archangel, Lamiastrum galeobdolon ‘Hermann’s Pride.’

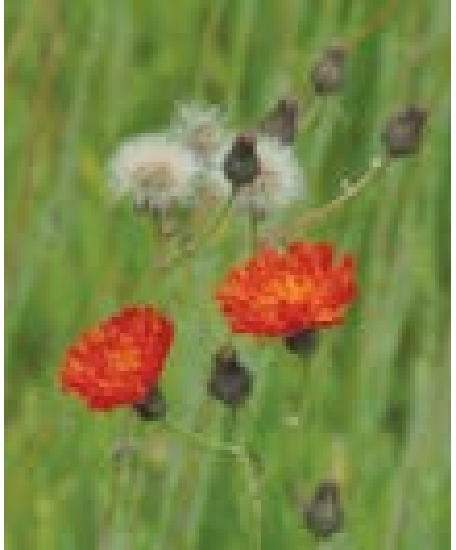

Orange hawkweed, Hieracium aurantiacum

Orange hawkweed, Hieracium aurantiacum

A small clump of orange hawkweed quickly becomes a large, solid mat of hairy leaves crowding out other plants. Don’t be tempted by its bright, orange flowers. This species is not garden worthy. Areas near Homer and other parts of the state are covered in orange hawkweed and chemical eradication programs have been undertaken in the Kodiak National Wildlife Refuge. Orange varieties of dwarf strawflower, Helichrysum bracteatum, can provide the same bright color as orange hawkweed in the garden. For more detailed information, contact Cooperative Extension for a copy of the “Orange Hawkweed” brochure published by the U.S. Forest Service or our publication on “Control of Orange Hawkweed”. Don’t be responsible for spreading this plant in your neighborhood or into the wild.

Butter and eggs (Toadflax), Linaria vulgaris

Butter and eggs (Toadflax), Linaria vulgaris

Butter and eggs looks non-threatening with its dainty, snapdragon-like flowers. It has been planted by unsuspecting gardeners, but if you’ve ever tried to eliminate butter and eggs from an area, you know how tenacious it can be. Plants can be seen growing from cracks in sidewalks and parking lots and along the railroad tracks in Willow. There are other species of annual and perennial Linaria, some more aggressive than others, but in Alaska none have spread to areas outside the garden like Linaria vulgaris. A close relative, dalmation toadflax is also a weed and should not be planted. Annual snapdragons can be used as an alternative to butter and eggs.

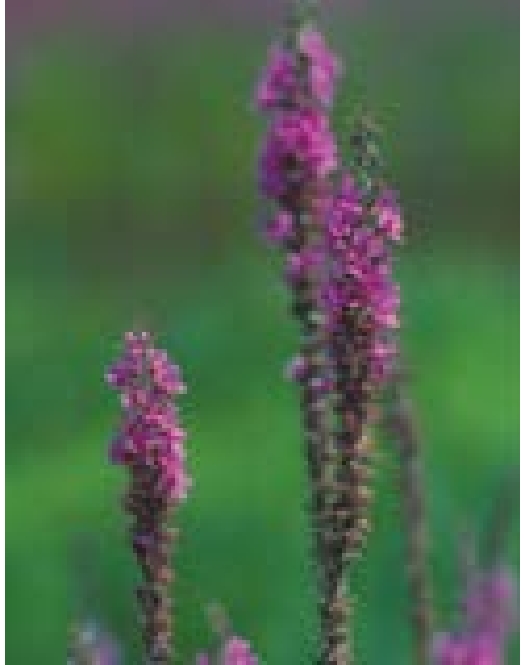

Purple loosestrife, Lythrum salicaria, L. virgatum

Purple loosestrife, Lythrum salicaria, L. virgatum

Nationwide, purple loosestrife is considered extremely invasive, especially in wet areas where the plant completely displaces other species and destroys wildlife habitat. Sale of the plant has been banned in 34 states, including Alaska, and many nurseries refuse to sell the plant even if it isn’t banned in their location.

In Alaska, purple loosestrife was first documented as escaping into the wild in October 2005. Numerous plants were pulled from an island in Chester Creek near Westchester Lagoon in Anchorage. The flower color of purple loosestrife is similar to fireweed which blooms earlier in the season. One plant that could be used as a substitute for purple loosestrife is Liatris spicata, commonly known as blazing star or prairie gayfeather. Its stiff spikes of purple or white flowers open from the top down. Plants grow 1½–3 feet tall depending on cultivar and are hardy in Southcentral Alaska. Other alternatives include blue or violet Salvia, Delphinium and native lupines.

Ornamental ribbon grass, Phalaris arundinaceae ‘Picta’

Ornamental ribbon grass, Phalaris arundinaceae ‘Picta’

Non-variegated Phalaris arundinaceae is more commonly known as reed canary grass, an aggressive, mat-forming grass that is difficult to eliminate once it becomes established. Reed canary grass has escaped and/or naturalized in 43 states, including Alaska, and in many Canadian provinces. According to Selected Invasive Plants of Alaska it is found along roadsides, ditches, wetlands, riparian areas, beaches and growing into lakes.

Variegated ribbon grass, Phalaris arundinaceae ‘Picta’ is likewise invasive and, as many gardeners can attest, is difficult to control. A better-behaved grass to use as an alternative is Miscanthus sinensis ‘Variegatus’, Japanese silver grass. Although websites and catalogs list it as a Zone 5 perennial, a nice clump labeled Miscanthus has been growing at the Palmer Visitor’s Center (Zone 3) for many years and the cultivar ‘Purple Flame’ proved hardy at the Alaska Botanical Garden until it was removed.

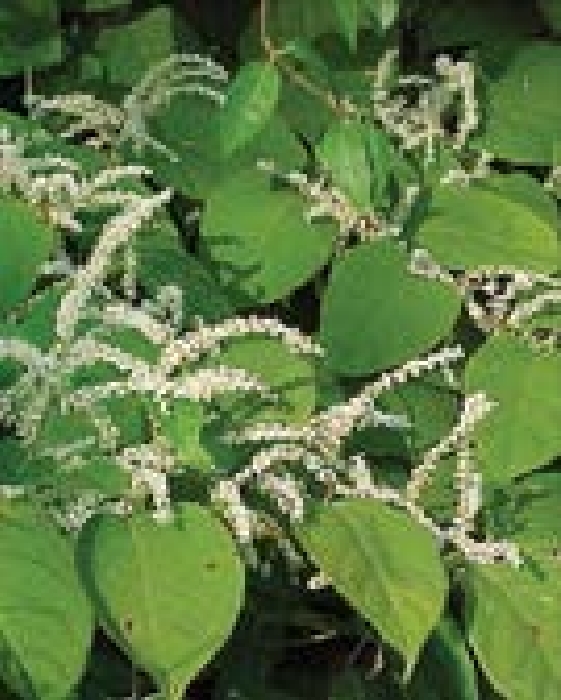

Japanese knotweed, Polygonum cuspidatum (Reynoutria japonica, Fallopia japonica), Bohemian knotweed (Polygonum x bohemicum)

Problematic in the Pacific Northwest, Japanese knotweed, and its cousins giant knotweed (P. sachalinense), and a hybrid between the two, Bohemian knotweed, are troublesome in Alaska. Local names for these plants include Chinese or Japanese bamboo because of the plant’s hollow stems. Many countries have been involved in research to try and eradicate this species where it has taken over. A brochure on Japanese knotweed published by the U.S. Forest Service in Alaska describes the impacts it has on native vegetation and wildlife. Rutgers Cooperative Extension claims Japanese knotweed is one of the most difficult to control species in the home landscape. In Southeast Alaska, large stands exist where plants have escaped cultivation. Plants can also be propagated inadvertently, when pieces of roots or stems are discarded in natural areas or waste places such as gravel pits. To find out more about this invasive species contact Cooperative Extension for a copy of the U.S. Forest Service brochure and for information on how to control existing stands.

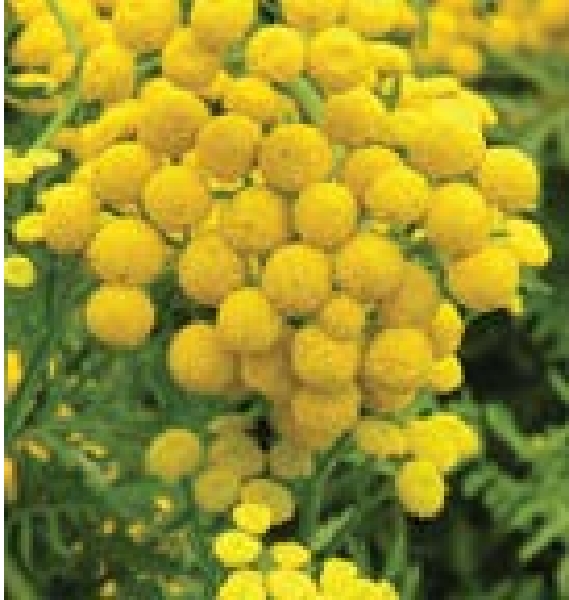

Common tansy, Tanacetum vulgare

This species can be found planted in both flower gardens and herb gardens. Gardeners try to control its spread by digging out unwanted rhizomes. Unfortunately, common tansy also spreads by seed and can be found growing in vacant lots and along the edges of woods and trails in Anchorage parks. Plants have also been found growing along roads in the Kenai Mountains. Common tansy is winter hardy and spreads aggressively in Fairbanks. Perhaps it’s still possible to prevent our roadsides from becoming covered with tansy by not planting this species in gardens. The plant can be a skin irritant and gloves should be worn when removing tansy from the garden or from places to which it has escaped.

Common mullein, Verbascum thapsus

Common mullein, Verbascum thapsus

The Verbascums are a group of very popular garden flowers because of their unusual,

tall spikes of flowers. Verbascum thapsus is a  common roadside weed in other parts of the country. This biennial has been recorded

as growing in open areas in Southcentral Alaska. The flowers of Verbascum thapsus

are not showy like many of its cousins. The wooly leaved Verbascum bombyciferum is

much more ornamental. Like common mullein, it is a biennial. Verbascum chaixii is

a reliably winter hardy perennial in Southcentral Alaska. Although not as tall or

large-flowered as V. bombyciferum, it has many flowering stems per plant. Other yellow

flowered mulleins may be winter hardy depending on which part of the state you are

located.

common roadside weed in other parts of the country. This biennial has been recorded

as growing in open areas in Southcentral Alaska. The flowers of Verbascum thapsus

are not showy like many of its cousins. The wooly leaved Verbascum bombyciferum is

much more ornamental. Like common mullein, it is a biennial. Verbascum chaixii is

a reliably winter hardy perennial in Southcentral Alaska. Although not as tall or

large-flowered as V. bombyciferum, it has many flowering stems per plant. Other yellow

flowered mulleins may be winter hardy depending on which part of the state you are

located.

Ornamental Jewelweed, Impatiens glandulifera

Ornamental Jewelweed, Impatiens glandulifera

The most commonly used local name for this species is Washington orchid. This plant may have been passed along to Alaska by gardeners from Washington, but this quick growing annual certainly isn’t an orchid. The plant is huge, often growing to eight feet tall. It seeds prolifically and has been documented growing in a large area along the beach in Haines. Ornamental jewelweed is known to thrive in riparian areas and can easily send seeds downstream. Its quick growth and ability to form dense stands allows it to out-compete other vegetation. As with other members of this genus, ripe seed pods explode when touched, ejecting seeds for many feet. Impatiens glandulifera may also be found listed as policeman’s helmet and Himalayan balsam. Impatiens noli-tangere is a much shorter, yellow-flowered wildflower native to Alaska, though it can also be an aggressive plant in the garden.

Scotch broom, Cytisus scoparius

Scotch broom is a woody member of the pea family which has become wide-spread on southern Vancouver Island and in many parts of the United States. It is considered a noxious weed in California, Hawaii, Idaho, Oregon and Washington. Scotch broom is already quite common in Ketchikan and has been planted in Sitka, Hoonah and Petersburg. Because it has overrun large areas in other parts of the country there is concern that it may do the same in Southeast Alaska. Scotch broom requires 150 frost-free days to produce seed.

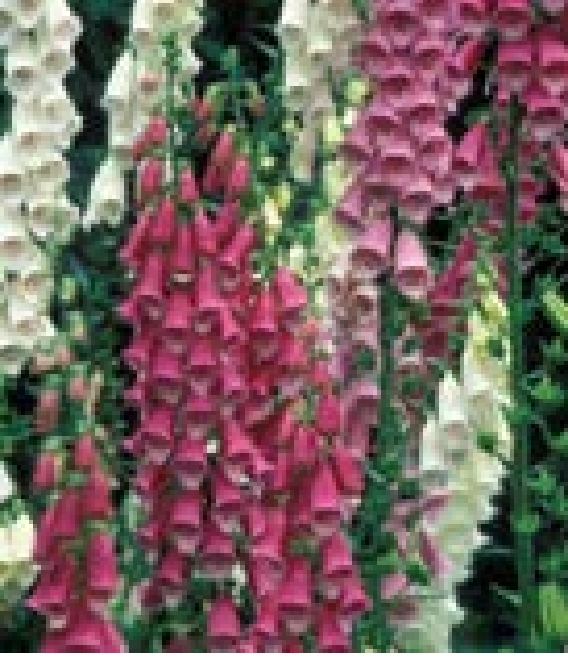

Foxglove, Digitalis purpurea

Foxglove, Digitalis purpurea

Although many gardeners are disappointed that this biennial does not usually survive the winter in Southcentral and Interior Alaska, foxglove has escaped cultivation in Southeast. It is very common in Sitka gardens. Gardeners in Juneau have reported its escape in their community. The flower is usually seen growing in ditches and it can form dense areas in disturbed sites. It is possible this species could threaten native plant communities. There are many other species of Digitalis that don’t have the reputation of escaping into the wild.

Sweet rocket (Dame’s rocket), Hesperis matronalis

Sweet rocket (Dame’s rocket), Hesperis matronalis

Often a component of non-native wildflower mixes, sweet rocket has also been planted by gardeners for its fragrance. Unfortunately, plants have escaped in 40 states, including Alaska where it is common in downtown Juneau, Kodiak and Sitka. Plants reproduce by seed and although usually listed as a biennial, can also be perennial.

St. John’s wort, Hypericum perforatum

St. John’s wort, Hypericum perforatum

St. John’s wort is planted because of its pharmaceutical properties although for this use it would be much safer to purchase from health food stores. Known as an extremely aggressive weed in the Pacific Northwest, St. John’s wort has escaped and/or naturalized in 44 states. It is a perennial that reproduces both by seed and vegetatively. Plants have been found growing in Hoonah, Sitka and Prince of Wales Island. Do not plant St. John’s wort in Southeast Alaska and monitor it carefully in Southcentral.

Creeping buttercup, Ranunculus repens

Gardeners are well aware of creeping buttercup’s aggressive tendencies. The species has escaped in 41 states and in many Alaska locations including Denali National Park, Girdwood, Seward, Homer, Juneau and Kodiak, where gardeners wage war against it on an annual basis. Plants can withstand low mowing when mixed in a lawn. When growing among taller species creeping buttercup grows to two feet. It thrives in moist locations but plants are not fussy. Gardeners in Southeast Alaska should not plant this species and gardeners in other parts of the state should think twice before planting what could become a problem.

Chokecherry species, Prunus padus and Prunus virginiana

Chokecherry species, Prunus padus and Prunus virginiana

Not all chokecherry species are invasive, but at least two (Prunus padus and Prunus virginiana) have proven highly invasive in all areas of Alaska south of the Arctic Circle. P. padus and P. virginiana are commonly known as chokecherry, European bird cherry, and May Day tree. They have spread to natural areas all over the state where planted, and communities with older infestations are taking note of how dense and prolific the species grow. Prunus species are cyanogenic, which has caused poisoning and death of moose in Anchorage. Prunus padus has formed dense stands in Anchorage, Hope and Talkeetna, Alaska, where it is able to shade out native vegetation. P. mackii is not known to spread as readily and may serve as an alternative. However, various forms of more edible cherries, including Nanking (P. tomentosa) and pie cherries, are successfully grown in Alaska and do not spread.

Siberian peashrub, Caragana arborescens

Siberian peashrub is an aggressive, spreading shrub in the pea family. The yellow flowers and fast growth have made it a popular ornamental hedge in Southcentral and Interior Alaska. It has spread to forested areas in Fairbanks, particularly around the University of Alaska campus. Southcentral has seen fewer escaped populations; however, it is thriving where it is growing in Anchorage and other areas.

Invasive Garden Species to Watch

Not all species that are aggressive in the garden will escape into Alaska’s wildlands and become problematic. The following compilation of species are garden flowers, trees and shrubs that should be watched to keep them from spreading. As we learn more about how these species behave in Alaska, our list of invasive garden species not to plant will likely change.

Oxeye daisy, Leucanthemum vulgare, is often used in non-native wildflower seed mixes and has been planted along roadsides. It is a gangly white daisy, that spreads from areas where it was originally planted in Southcentral Alaska. It is also hardy in the Interior. There are many cultivars of the more ornamental Shasta daisy, Leucanthemum X supurbum, which can be grown. They are not as winter hardy as the oxeye daisy but much better behaved. Another alternative is the native arctic daisy, Dendranthema arcticum.

Another aggressive spreader is sneezeweed, a relative of yarrow. Its scientific name is Achillea ptarmica. On the Kenai peninsula it is known as Russian daisy. In the garden, this white flower spreads readily by seed. It has escaped and/or become naturalized in 18 states, including Alaska.

Two commonly used groundcovers that have reputations as being weedy Outside include bishop’s goutweed, Aegopodium podagraria and spotted deadnettle, Lamium maculatum. Many Alaskan gardeners are raising a red flag about bishop’s goutweed, too. It spreads from flower gardens into the lawn and is difficult to eradicate once you decide you don’t want it. Spotted dead nettle is more often called by its genus name, Lamium. Many new cultivars have been developed in recent years, even though it is a spreader. Both of these species should be watched to make sure they don’t escape cultivation.

Growing tight to the ground, creeping Veronica, Veronica repens, can show up in places where it is not wanted. This species of Veronica was once banned from beds at the Alaska Botanical Garden but can still be found growing in the lower perennial garden. If it gets into your lawn, you’ll be sorry. Another Veronica, V. grandiflora, the Aleutian speedwell, is an Alaskan native, but taken from the Aleutian Islands and brought into the garden, this little Veronica can really spread.

Garden flowers that spread themselves around by seed include maiden pink, Dianthus deltoides, and the non-native forget-me-nots. Spreading outside the garden, maiden pink has escaped and/or become naturalized in at least 23 states. Forget-me-nots are commonly planted because gardeners think they are planting the Alaska state flower. Our native forget-me-not is Myosotis alpestris subspecies asiatica. It doesn’t have the tendency to spread like the non-native species. Often, seed packets don’t even mention the species of Myosotis they contain. Other times they are mislabeled.

Many Anemones are indigenous to Alaska. The snowdrop windflower, Anemone sylvestris is not and should be watched because of its strong tendency to spread by rhizomes. The large yellow flag iris, Iris pseudacorus, grows more prolifically in wet locations than typical garden soil. Gardeners should keep an eye on it, especially in Southeast.

While Campanula rapunculoides has the reputation of being the most invasive Campanula, there are others that should be watched. The clustered bellflower, Campanula glomerata has escaped and/or naturalized in 12 states including Alaska. Korean bellflower, Campanula takesimana has also proven to be a strong spreader in Southcentral Alaska and gardeners should take care to see that it does not escape. Suggested alternatives for these species are listed under Campanula rapunculoides at the top of this page.

The genus Centaurea includes many bad weeds so it makes sense that related garden flowers should be planted with caution. The annual bachelor’s buttons or cornflower has escaped in 48 states and is often included in non-native wildflower seed mixes in Alaska. Globe centaurea, Centaurea macrocephala, is designated as a “Class A Noxious Weed” in Oregon and Washington. Perennial bachelor’s buttons have escaped and/or naturalized in other states and is known to spread itself around in Alaskan gardens.

In addition to St. John’s wort, which should not be planted in Southeast, there are a number of herbs which should be watched. Chives, Allium schoenoprasum, seed prolifically if spent flowers are not removed. While many varieties of mint, Mentha sp. are not winter hardy in Southcentral Alaska and areas that are colder, some species are known to be very

invasive. Catnip, Nepeta cataria, is a weed in many parts of the country. Gardeners growing it should make sure to pull out unwanted seedlings. Comfrey, Symphytum officinale, has been banned from more than one garden because of its aggressive tendencies.

Not all garden species to keep an eye on are herbaceous. There are trees and shrubs which have started spreading beyond the home/commercial landscape. Tatarian honeysuckle, Lonicera tatarica, has completely degraded woodland composition in parts of the Midwest and should be watched to make sure that it does not become established in the wild in Alaska. European mountain ash, Sorbus aucuparia, has escaped cultivation in Anchorage and Southeast Alaska where native species of mountain ash exist.

As gardeners, what can you do?

- Don’t plant flowers, trees and shrubs which are known to be invasive.

- Watch species that have the potential to become

troublesome and help share information.

Alaska wild iris - Order from reputable nurseries that are not likely to mislabel plants or sell weedy seed mixes.

- Don’t share potential problems with other gardeners.

- When you purchase new plants, watch to make sure you don’t introduce weeds hitchhiking in pots or root balls.

- Make sure you don’t introduce problems by planting nonnative wildflower seed mixes which contain invasive species or weed seeds.

Human actions are the primary means of invasive species introductions. Gardeners can be part of the solution. Don’t plant invasive species intentionally.

Publications:

“Invasive Plants of Alaska,” 2005. AKEPIC – Alaska Exotic Plants Information Clearinghouse, Alaska Association of Conservation Districts Publication, Anchorage, Alaska

“Selected Invasive Plants of Alaska,” USDA Forest Service R10-TP-130B, 2007

“Control of Bird Vetch (Vicia cracca),” UAF Cooperative Extension Service publication PMC-00341

“Best Management Practices: Controlling the Spread of Invasive Plants During Road Maintenance,” UAF Cooperative Extension Service publication PMC-00342

“Control of Orange Hawkweed (Hieracium aurantiacum),” UAF Cooperative Extension Service publication PMC-00343

“Invasive Plant Issues: Control of Invasive Chokecherry Trees,” UAF Cooperative Extension Service publication PMC-00345

Websites:

U.S. Forest Service, Forest Health Protection, Alaska Region website, where many of the above publications can be found: USDA Forest Service Region 10 Forest and Grassland website

UAA Natural Heritage Program, Plant Invasiveness Ranking Project: Alaska Natural Heritage Program website

Gino Graziano, Extension Invasive Plants Instructor. Originally written by Julie Riley, Agriculture and Horticulture Agent, and Jamie Snyder, former Invasive Plants Program Instructor.

Revised October 2021