For best exprience view on a desktop computer using full screen.

0%

For best exprience view on a desktop computer using full screen.

Chapter Two|

Scroll Down

Renowned Athabaskan elder Poldine Carlo speaks during the Troth Yeddha' Park and Cornerstone rededication ceremony which kicked off UAF's centennial celebration on July 6, 2015.

UAF photo by Todd Paris

“[She] was the first Native person to graduate from the university, and she was my home ec teacher in Eklutna. … I was so proud of her.”

— Poldine Carlo, Athabascan elder, 2015 Troth Yeddha’ Park dedication

Louise Harper and baby Flora, Stevens Village, 1912-1914. From the Rivenburg, Lawyer and Cora Photograph Album.

File: UAF-1994-70-25, Collection: Rivenburg, Lawyer and Cora Photograph Album. 1910-1914 (bulk).

Alaska and Polar Regions Collections, Elmer E. Rasmuson Library, University of Alaska Fairbanks.

After graduation from UAF, she married, taught at several Bureau of Indian Affairs boarding schools around the state and then worked at the Anchorage municipal library for decades.

Harper’s brother, Francis, also attended UAF before serving in World War II. His B-17 bomber was shot down in 1943 and he was imprisoned in a German camp until 1945.

Her uncle, Walter Harper, in 1913 joined Episcopal Archdeacon Hudson Stuck’s expedition to climb Denali. He became the first person in recorded history to stand on the mountain’s top.

Prospectors and miners turned students are seen during one of the mining classes offered.

File: UAF-1958-1026-8 Collection: University of Alaska, General File, Vertical File--University of Alaska--Individuals.

Alaska and Polar Regions Collections, Elmer E. Rasmuson Library, University of Alaska Fairbanks.

Of the 35 students who graduated in 1941, almost half received degrees from the School of Mines. Enrollment at UA hit a record 307 that year; 88 were mining students.

In addition, about 500 people were taking six-week mining extension courses at multiple towns across the state.

The interest in mining was in part driven by rising gold prices. The federal government, which had set the price at $20.67 per ounce since 1879, brought the price to $35 in a two-stage increase in 1933 and 1934.

A Fairbanks Exploration Co. dredge works near Fox in 1938.

File: UAF-1988-168-34 Collection: W.H. Carroll photographs.

Alaska and Polar Regions Collections, Elmer E. Rasmuson Library, University of Alaska Fairbanks.

In the late 1930s, the school established three five-year degrees in mining topics, in part to give students more expertise but also to allow them to acquire a more well-rounded schooling in the arts and sciences. Patty, in particular, was known for his desire to civilize his sometimes rough mining students.

“Ernest Patty was dean of the School of Mines my first three years, and he occasionally lectured on the need to learn social graces as well as mining. We did not take him seriously enough, as I am sure that many others also realized how important the social graces are when you reach the executive level.” — Patrick O’Neill ’41, quoted in “Rock Poker to Pay Dirt,” by Leslie Noyes.

“Someday, you may be called to New York and invited to lunch in a club. It’s important for you to be at ease and to know which fork to pick.” — Ernest Patty, in his 1969 book “North Country Challenge,” explaining why he asked home economics Professor Lola Tilly to hold weekly teas, which he expected his mining students to attend.

Enrollment fell dramatically as the United States entered World War II and young men entered the military instead of college. Faculty members were also called away. The military leased most of campus.

Hess Hall served as a military hospital during World War II.

Photo from Wide World Photos - A-38922/18749-SM-3/18/44-F-FS-37-9.35A

Buildings burn after the first Japanese attack on Dutch Harbor, Alaska, June 3 1942.

Photo by US Air Force via Wikimedia Commons

When Japan attacked Pearl Harbor on Dec. 7, 1941, Alaskans felt vulnerable. Six months later, when Japan’s bombs killed several dozen soldiers at Dutch Harbor and its army captured Kiska and Attu islands, Alaskans and the rest of the nation became genuinely alarmed. An enormous military buildup began in the territory.

As young men entered the military and young women went to work in war-related jobs, university enrollment dropped from more than 300 in 1940 to fewer than 70 students by 1943.

A Japanese ship burns in a harbor at Kiska Island after an 11th Air Force raid.

Photo by US Air Force via Wikimedia Commons

The war decimated the ranks of faculty, many of whom also entered the military. The university had 38 faculty members in 1941; two years later, only eight among them remained.

The shortage of instructors forced the university to drop its rule that prohibited the employment of married women. For example, Lola Cremeans Tilly, head of home economics starting in 1929, had left the department in 1937 after marrying Gray Tilly but returned to work in 1942 when the policy changed.

Landing boats pour soldiers and equipment onto the beach at Massacre Bay, Attu Island.

Photo by Library of Congress

The war literally turned the campus into a military base. Almost two-thirds of the square footage in university buildings was leased to the military. Hess Hall, the women’s dorm, became a hospital. The Army ran the dining operation.

This picture depicts this catastrophe, the mangled aircraft can be seen against the wall of the Eielson Building as a small group of bystanders probably students, scrutinize the accident site. Another group of onlookers and what looks like an emergency vehicle is seen in the foreground.

File: UAF-1958-1026-1992 Collection: University of Alaska, General File, Vertical File--University of Alaska--Buildings, Vertical File--University of Alaska--General.

Alaska and Polar Regions Collections, Elmer E. Rasmuson Library, University of Alaska Fairbanks

On July 12, 1944, a young soldier died when his small plane hit the Eielson Building, but his full story remains a mystery.

A group of soldiers from the medical staff at the temporary Army hospital in Hess Hall were playing volleyball when the plane swooped over them. On a second pass, it snagged an antenna cable and hit the Eielson Building’s then-northwest corner. It took hours to extract the pilot’s body.

A newspaper article at the time said the young man was a student pilot who had taken off in Anchorage. The name initially was withheld pending notification of kin, but his identity was never reported in later editions.

Little more has emerged since. Twelve years after the incident, a newspaper story reported that the pilot had been a soldier whose ex-girlfriend worked in the Eielson Building.

“This was a war year. Many of the activities conducted at the university were of a confidential military nature,” journalism student William King wrote in the Fairbanks Daily News-Miner on April 23, 1956. “Perhaps because of the delicacy of the situation, or because higher authority ordered a silence which since then has never been broken, the complete story never reached the public.”

King’s article neither identified the woman nor quoted her directly, but it contained several unattributed statements of fact. He said the woman was reticent but confirmed she had ended her relationship with the pilot earlier that summer. She left Fairbanks as the summer ended that year, King wrote.

“We are left with a still visible mark, in the southwest (sic) corner of the Eielson Building, and a riddle: Did the group of men playing volleyball on a warm summer night in 1944 witness an avoidable accident, a poetic but senseless gesture or a fortunate miscalculation?” King wrote. “How would you have it?”

“Most of the young instructors who joined the teaching staff during the past few years will be missing at next September’s faculty meeting.”

— Charles Bunnell, Farthest North Collegian, May 1, 1942

“Army ‘chow’ was far more plentiful and varied than the University Club had offered and the civilian boarders were duly appreciative.”

— William Cashen in “Farthest North College President”

The Farthest North Collegian, Dec. 1 1948. Download the paper (PDF).

Alaska and Polar Regions Collections, Elmer E. Rasmuson Library, University of Alaska Fairbanks

Some members of the 1947 Legislature actually heckled President Bunnell when he presented his budget request for the next two years. He took them on and ended up with more than his initial request.

However, a bigger problem arose when legislators appropriated about $10 million for territorial operations in the fiscal 1948-49 biennium. Taxes were expected to raise only $6.25 million. So the territory’s administrative board froze many agency accounts, including the university’s.

By November 1947, the university’s checking account was down to $1,000. “Lack of Funds May Force University to Close Doors Before School Year Ends” said the top headline in the Dec. 1 edition of the Farthest North Collegian.

Bunnell advanced the university $20,000 for the December payroll and used some accounting maneuvers to keep the doors open during the spring semester. Regent Austin “Cap” Lathrop, who owned the main coal mine in Healy, led an effort to solicit interest-free loans from the business community and offered $25,000 himself. Pledges ended up totaling $200,000. Bunnell put up the final $5,000. Gov. Ernest Gruening promised to repay the loans, even though the territorial treasurer said they had been illegal under federal law.

The Legislature adopted income and property taxes in 1949, relieving the territory’s budget shortfall and providing a large budget increase for the university.

“The University would continue if it could do so by labor alone. But food costs money. Books cost money. Electricity costs money. Coal costs money. And the University has no money.”

— Farthest North Collegian, December 1947

“You have to be 50 percent statesman and 50 percent sonofabitch,”

— Charles Bunnell on the qualifications needed to be a university president, as quoted by state Sen. John Butrovich in “The College Hill Chronicles,” by Neil Davis, page 182

“That day when Bunnell told us he couldn’t meet the payroll, Cap asked him how much he needed, and Bunnell said $10,000. Cap got up and went over to the telephone. He called his bank and ordered them to cut a check for $10,000, and then he told Bunnell to send somebody down to pick it up. This was a real education for me, to see things done this way.”

— UA Regent Leo Rhode, interview reported in “The College Hill Chronicles,” by Neil Davis, page 224

After a dozen years of advocacy from Bunnell and others, Congress authorized the Geophysical Institute to conduct polar atmospheric and seismic research in 1946. But the nearly $1 million approved wasn’t actually appropriated. For the next two years, one house of Congress would put the money in a spending bill, only to have the other strip it out.

The money finally passed both houses in 1948, but it came with a last-minute zinger: The institute’s buildings and equipment would remain “the property of the United States.” The caveat came from Rep. Everett Dirksen, who had an unrelated beef with Bunnell.

Dirksen was sure Bunnell had been siphoning off federal money intended for the agricultural experiment stations to support the university. As retribution, the congressman had already succeeded in removing the experiment stations from the university’s control, an action that wasn’t rescinded until after Bunnell left the presidency.

Nevertheless, the Geophysical Institute finally opened in 1949 in a building just west of today’s Wood Center.

The institute’s first director was Stuart Seaton, who had formerly worked as observer-in-charge of the federal Coast and Geodetic Survey’s College Observatory. The observatory had been created in 1941 on property leased from the university, and Seaton arrived as an employee.

Seaton didn’t last long as director. A close ally of Bunnell, Seaton perceived a series of slights from the new UA President Terris Moore. He and many of his staff tendered their resignations to the regents in May 1950. The regents accepted, shocking many people from campus to Washington, D.C.

Meanwhile, across the Earth in England, Oxford University’s Sydney Chapman, the world’s top space scientist, was nearing the mandatory retirement age of 65. Chapman wasn’t ready to retire, though. So, after meeting the Geophysical Institute’s interim director William Wilson in November 1950, Chapman signed on as advisory scientific director and began spending a few months a year on campus.

“He alone was capable of putting the Geophysical Institute and the University of Alaska on the map of the scientific world, and he was doing just that,” wrote Neil Davis, a UA alumnus, professor emeritus and author of “The College Hill Chronicles.”

The Geophysical Institute moved to its present-day location on West Ridge in 1970, the year Chapman died. The institute’s original building is named for him.

“I went over as the lone witness and figuratively got down on my knees,”

— Alaska Territorial Delegate E.L. “Bob” Bartlett, describing his appeal to a U.S. Senate committee for money to build the Geophysical Institute in 1948.

Terris Moore, dubbed the flying president for his exploits in small aircraft, replaced President Bunnell in 1949, but Bunnell didn’t go anywhere. He kept his residence on campus until his death in 1956, and his presence contributed to Moore’s short four-year tenure.

Bunnell was suffering badly from diabetes by 1948. His age, the stress of the long hours and the never-ending struggle for money also had taken a toll. His wife had gone Outside with their daughter almost 20 years earlier. He resigned, effective July 1, 1949.

The regents hired Terris Moore, a 40-year-old East Coast financial consultant who held a trifecta of qualifications appealing to Alaskans — a doctorate in business from Harvard, an ability to fly his own two-seat Taylorcraft airplane and a reputation as a leading mountaineer buttressed by ascents of Denali and other Alaska peaks. Moore had even flown himself from Boston to Alaska in March 1949 to seek the job.

The four older members of the board seemed unconvinced, though. Observers expected a 4-4 stalemate at the May 1949 vote on Moore’s candidacy. But the tally was 5-3 in favor.

The defector? Harriet Hess, the longtime regent who 28 years earlier had steered the board to hire Bunnell.

The university initially had nowhere to house Moore’s family when they arrived in June. Bunnell remained in the president’s residence. The Moores stayed in Hess Hall’s infirmary for seven weeks before moving into a new house.

During the next four years, Moore replaced Bunnell’s authoritarian style with an approach that encouraged faculty and student involvement. He upgraded standards for the hiring and performance of faculty members. He guided establishment of the first community colleges elsewhere in the state. And he oversaw the rapid post-war expansion of buildings.

However, Moore found himself mired in several difficult controversies and often was unable to gain Bunnell’s support. The president emeritus lived on campus, consulted at regents’ meetings and kept an office in Eielson Building’s Room 207 across the hall from Moore’s office. Moore announced his resignation in May 1952 and left a year later.

Bunnell continued to live on campus until September 1956. Poor health forced him south to a nursing home in San Francisco, where his daughter, Jean, lived. He died there on Nov. 1, 1956.

“It was Mrs. Luther C. (Harriet) Hess of Fairbanks, that parsimonious lady who had sat on the board since 1917 busily taking notes for the minutes and having little to say. Now that fair day in May, with one word written on a scrap of paper, she had changed the direction of the University of Alaska’s history. It was probably the most important vote she ever took in her 32 years on the board. She did it knowing that, seconds later, she would be facing up to the baleful stares of three of the territory’s most influential men, her long-time friends and coworkers: Cap Lathrop, Senator Nerland and Judge Bunnell.”

— Neil Davis, UA alumnus, professor emeritus and author of “The College Hill Chronicles,” (page 249) explaining Harriet Hess’ role in selecting Terris Moore as the university’s second president

“We suffer taxation without representation, which is no less ‘tyranny’ in 1955 than it was in 1775. Actually it is much worse in 1955 than in 1775 because the idea that it was ‘tyranny’ was then new. Since the revolutionaries abolished it for the states a century and three-quarters ago, it has become a national synonym for something repulsive and intolerable.”

—Former territorial Gov. Ernest Gruening, speaking to the Alaska Constitutional Convention

E.L. “Bob” Bartlett, as the territory’s elected delegate to Congress since 1944, offered the convention’s first major address. Bartlett had grown up in Fairbanks. He attended but did not graduate from the university, then worked as a local newspaper reporter and a placer miner before getting into politics. He focused on a topic about which there was “almost no pre-Convention talk in Alaska,” he said.

“The story of Alaska natural resources has too often been one of exploitation with very little of the great wealth extracted going to pay for necessary governmental services and for the permanent development of a sound economy for the people,” Bartlett said. The convention delegates, he said, must give industry and the federal government “notice that Alaska’s resources will be administered, within the bounds of human limitations and shortcomings, for the benefit of all of the people.”

Ernest Gruening, the territory’s appointed governor from 1939 to 1953, gave a short opening-day speech then returned the next day to deliver a scathing assessment of the federal government’s treatment of Alaskans.

“We meet to validate the most basic of American principles, the principle of ‘government by consent of the governed,’” Gruening began. “We take this historic step because the people of Alaska, who elected you, have come to see that their longstanding and unceasing protests against the restrictions, discriminations and exclusions to which we are subject have been unheeded by the colonialism that has ruled Alaska for 88 years.”

Gruening compared Alaska’s grievances to those made against King George in the Declaration of Independence.

Comparing Alaska’s quest to the American Revolution was already a popular rhetorical theme in the fight for statehood. Alaskans had elected 55 delegates to the convention, a number that matched the number of delegates in 1787 in Philadelphia.

Alaskans chose a variety of sorts to represent them – quite a few attorneys and businessmen but also miners, pilots, homemakers, fishermen, a clergyman and a photographer. Six were women; one was Alaska Native.

The delegates gathered in the Student Union Building, now Constitution Hall. For 75 days, they read, consulted with experts, debated and finally wrote the Alaska Constitution. Sharp disagreements arose, but delegates worked them out in the collegial environment.

“Mr. President, I met with some of the attorney members on the matter of this amendment of mine,” Fairbanks delegate Frank Barr announced on the 40th day while working on the rules for ballot initiatives, “and at first they did not exactly agree, but, with great effort, bloodshed was avoided." Delegates signed the constitution Feb. 5 and then adjourned Feb. 6, 1956. That day, the temperature, which had dropped to 52 below on Jan. 5, only fell to minus 25 at the university’s agricultural experiment station.

Alaska voters ratified the proposed constitution in an election in April by a 2-1 ratio. That helped spur Congress to pass a bill on June 30, 1958, outlining the terms of statehood. Voters endorsed it in August 1958 — by a 5-1 ratio. In November, they elected Bartlett and Gruening as their first U.S. senators and Ralph Rivers, a convention delegate, as their first U.S. representative.

On Jan. 3, 1959, President Dwight Eisenhower signed the proclamation declaring Alaska the 49th state in the union.

“We write on a clean slate in the field of resources policy. Only a minute fraction of the land area is owned by private persons or corporations. Never before in the history of the United States has there been so great an opportunity to establish resources policy geared to the growth of a magnificent economy and the welfare of a people.”

—E.L. “Bob” Bartlett, delegate to Congress from the Territory of Alaska, speaking to the Alaska Constitutional Convention

“A sense of both history and of destiny sat with the 55 delegates throughout their deliberations at Constitution Hall on the campus of the University of Alaska at College, just a few miles west of Fairbanks. Many factors contributed to this: the number 55, chosen in emulation of the 55-member Philadelphia convention of 1787; the belief of Alaskans in the limitless future of their vast land and their pride in being the last of the pioneers of the old tradition; the personal dedication evidenced by the members of the convention; and the university setting which was conducive to the remarkable industry and concentration which they devoted to their work.”

—John Bebout, a New York University professor and consultant to the Alaska Constitutional Convention, writing after its conclusion

YouTube film provided by Alaska Film Archives, a unit of the Alaska and Polar Regions Collections and Archives in the Elmer E. Rasmuson.

In this 1957 cartoon by Helen Fischer, a fisherman resembling 1956 presidential candidate Adlai Stevenson seeks to hook Alaska and Hawaii into the 49th and 50th states.

File: UAF-1976-21-1301 Collection: Ernest H. Gruening Papers, 1914-[1959-1969] 1974.

Alaska and Polar Regions Collections, Elmer E. Rasmuson Library, University of Alaska Fairbanks.

Even as the university grew rapidly and evolved into a more modern institution under the guidance of Ernest Patty during the 1950s, rowdy students continued to challenge the respectable atmosphere the president desired. Patty had enough in 1956 and banned alcohol. Students protested by planting a 400-pound headstone with the epitaph “Here lies tradition” in 1957. Before the university administration could remove the stone, it was spirited away. Since then, it has been stolen or passed along by students and alumni.

Ernest Patty

Photo from the UA Journey website.

Ernest Patty, who succeeded Terris Moore as president of the University of Alaska in 1953, had a longstanding reputation as a crusader against unrefined behavior among students.

Patty, a mining engineer, was one of the original faculty members when the college opened in the fall of 1922. Later, after observing the rough manners among some of his mining students, he arranged with home economics Professor Lola Tilly to hold weekly teas. He expected his students to attend.

Patty’s son, Stan, recalled years later the atmosphere encouraged by his parents. “The university was the cog, the main cog I think, in making Fairbanks the civilized place it was,” Stan said in a 1991 interview.

Ernest Patty resigned his faculty position in 1935 to develop his own successful mining company in the upper Yukon River region, with dredges at Coal and Woodchopper creeks. The family then moved to Seattle. When the regents needed to find a successor to Moore in 1953, Patty accepted their invitation. Back on campus, he launched a rapid expansion of university buildings that extended well into the 1960s.

Despite progress on the facilities front, unruly students still regularly challenged Patty’s sense of decorum.

For the 1955 Miner’s Ball, recent School of Mines graduate Don Stein pooled about $125 and bought enough alcohol to heavily spike the punch, according to Leslie Noyes’ book “Rock Poker to Pay Dirt.” Chaperones in previous years had ignored the practice, but the 1955 recipe, which Stein got from a bartender friend, was different.

“It was really smooth, so people didn’t realize how strong it actually was until they started getting intoxicated,” Stein said. “Dr. Patty got a little peeved. Not too long afterward, he put out a notice banning alcohol on campus.”

Patty issued the order in November 1956, after a fight at the annual Starvation Gulch festivities.

Student protests culminated on March 22, 1957, in a vigil at Constitution Hall. Students dug a hole, threw in several hundred beer bottles and planted a 400-pound headstone with a welded plate declaring “Here lies tradition.” The protests did not move the president, nor his successor, William Ransom Wood. The ban continued until 1972.

Patty ordered the headstone to be removed, but someone took it first. Possession has since passed down through numerous hands, sometimes transferred via good-natured thievery. At some point, the stone broke into several pieces. In 1992, campus police secured the pieces during an unrelated investigation.

“Anxious to get rid of the stone, the university looked the other way in early 1993 when it was stolen once again, enabling tradition to live on,” wrote UAF history Professor Terrence Cole in his book “The Cornerstone on College Hill.”

“The edict caused an immediate sensation among the students, and the campus was in an uproar last night as groups of students gathered to discuss the ban and ways in which it might be subverted.”

—The Polar Star, Nov. 30, 1956, reporting on Patty’s prohibition of alcohol on campus.

“Over the years, that stone has been found and stolen and discovered again by various people. At one point I heard the stone was in South America. But where it is now is a mystery to me.”

—Don Stein, quoted in Leslie Noyes’ 2001 history of the School of Mines, “Rock Poker to Pay Dirt”

Two university biologists lost their jobs after protesting the way their work was being used by the U.S. Atomic Energy Commission. The commission had contracted with the university to study the effects of using nuclear explosions to create a harbor near Point Hope in northwest Alaska.

The U.S. Atomic Energy Commission decided in 1958 that it would be a good idea to excavate a harbor near Point Hope, Alaska, using six nuclear blasts. The commission called it Project Chariot.

The next year, the University of Alaska got a $107,000 contract from the AEC to study the environmental impacts of the proposal. The university, demonstrating its enthusiasm for the idea, granted an honorary doctorate to Edward Teller, the “father of the H-bomb” who was then directing an AEC lab in Livermore, California.

Les Viereck

Photo from the Boreal Ecology Cooperative Research Unit (BECRU) website.

As the environmental research progressed, several university scientists objected to the way AEC officials downplayed the risks of radioactive fallout. In 1961, biologist Les Viereck resigned from the contract work in protest. His decision cost him his teaching job — the university administration declined to keep him on staff. The next year, biology Professor William Pruitt was fired after he resisted modifications to his report to the AEC and publicly criticized the proposal.

William Pruitt

Photo from the Tiaga Biological Station website.

The AEC dropped Project Chariot in August 1962 in response to the growing criticism from scientists, environmental activists and Alaska Native people.

The university’s treatment of Viereck and Pruitt under then-President William Wood remained controversial for decades. After a campaign by faculty, UAF presented the two researchers with honorary doctorates at the 1993 commencement.

The article, Project Chariot: How Alaska escaped nuclear excavation, published in The Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists December 1989 issue.

“It has often been stated that a scientist working under a government contract should not worry about the interpretation of the data he is hired to collect. I strongly disagree with this attitude and feel that it is the duty of every scientist to protect his data and to be sure that it is interpreted correctly. A scientist’s allegiance is first to truth and personal integrity and only secondarily to an organized group such as a university, a company, or a government.” —Les Viereck, Dec. 29, 1961, in his resignation letter to President Wood, as quoted in “The Firecracker Boys,” by Dan O’Neill

President William Wood oversaw an enormous expansion of the university’s facilities during the 1960s. After finishing his 13-year stint as president, he remained in Fairbanks and participated in many civic activities.

William R. Wood succeeded Ernest Patty, becoming the fourth president of the university in 1960. Wood had previously served as the vice president of the University of Nevada. He held a doctorate in English.

Under Wood, the university’s expansion rate eclipsed even Patty’s rapid pace. The Wood years brought the Elvey, Irving and Arctic Health Sciences building in the West Ridge research complex; the Patty Center; the Lathrop, Moore, Bartlett and Skarland dorms; the Lola Tilly and Hess commons; the Rasmuson Library; the Fine Arts Complex; the heat and power plant in the Ben Atkinson Building; the Gruening Building; and Wood Center.

Wood retired from the presidency in 1973. His 13 years in the position are still second only to Charles Bunnell’s 28 years.

Wood remained in Fairbanks for the remainder of his life. City voters elected him mayor for a two-year term in 1978. In the early 1980s, he founded Festival Fairbanks, a local civic organization that advocated for construction of Golden Heart Plaza and the pedestrian bridge over the Chena River, both in downtown Fairbanks. For many years, Wood wrote a regular column in the Fairbanks Daily News-Miner that often advocated for greater economic development.

Wood died in 2001.

““Where but in Alaska could one find a single university with a fur farm, a musk ox herd, a square mile of glacier, several tons of bones of prehistoric animals, an ice station on the polar ice cap 400-odd miles north of land’s end, a world-famous scientist with a special alarm system to awaken him whenever the aurora borealis flashes across our northern skies, two satellite tracking stations, no social fraternities, no sororities, and no losing football team for the alumni to use as an excuse for firing the president?”

—William R. Wood’s inaugural address to the university in 1960

Taking over a student-run radio station with a feeble signal, the university pioneered Alaska’s public broadcasting efforts, first with KUAC-FM in 1962 and then with KUAC-TV in 1971.

The university’s radio station, KUAC-FM, began broadcasting at 3 p.m., Oct. 1, 1962. UA President William R. Wood delivered remarks before announcer Larry Holmstrom introduced Beethoven’s “Emperor Concerto.”

Students had created a low-power radio station, KUOA, in 1955. The university bought out the station in 1961 and expected to keep the call sign. But the University of Arkansas was already using it. So the Federal Communications Commission authorized “KUAC,” representing the “University of Alaska in College.”

The first KUAC broadcasts, from studios on the third floor of Constitution Hall, used an old transmitter purchased in Seattle. The original frequency was 104.7 megaHertz. That changed to 89.9 mHz years later when the military relinquished the lower range of the FM radio spectrum in Alaska.

In 1971, the station moved its studios to the ground floor under the Regents’ Great Hall, where they remain today. KUAC began broadcasting television late that year. The station has grown into one of the most popular in the nation, as measured by its share of the local broadcast audience and its fundraising success.

“The basic purpose of the station, according to Prof. Lee H. Salisbury, is practical training in radio broadcasting. Professor Salisbury heads the Department of Speech and Drama, College of Arts and Letters. Professor Salisbury added that he believes that one of the biggest problems of Alaska radio is the lack of trained Alaska announcers. He said that a manager of a local station has no way of knowing if a trained applicant announcer (or engineer) from the Southern 49 will like Alaska and stay. A person trained in Alaska will stay in Alaska, he believes.”

— An Aug. 31, 1961, University of Alaska news release about plans for a campus radio station

“I can tell you only what I have already told you. We are not programming ‘rock & roll’ music and we are not airing a religious program. … Since complaints like those you have received about our programming are bound to continue (everyone thinks his taste in programming is universal) I would suggest that they be referred directly to me. I believe it’s my job to handle them.”

— Charles Northrip, KUAC manager, in a 1964 memo to Charles Keim, dean of arts and letters

University of Alaska’s sports teams, formerly known as the Polar Bears, became the Nanooks in 1964. With a new sports center finished the year before, the Nanooks had a modern facility in which to practice and play.

Sports had been a part of the university since its early years, even if collegiate competitors had been few and far between to start. The college’s first teams, dubbed the Polar Bears, often took on opponents drawn from the community, military or high schools.

But by the late 1950s, even most Alaska high school teams had better gymnasiums than the Polar Bears, noted Audrey Loftus, the first alumni association director, in a letter to legislators. She appealed to them for money to build a modern sports facility.

At that time, the university mostly got by with the building eventually christened Signers’ Hall. The gym floor there was smaller than a standard basketball court, and only about 50 spectators could squeeze into the balcony.

The drive to create a modern facility resulted in the Patty Center, completed in 1963. Loftus, the alumni director, turned over the first shovel of dirt for the ceremonial start of construction.

The next year, university teams were renamed the Nanooks, the Inupiaq word for polar bear.

In addition to a basketball court with bleachers capable of holding 3,500, the Patty Center had a swimming pool, vast shower and locker rooms, a rifle range, a ski room, handball courts and offices for ROTC and athletic department administrators.

The "Beluga" an inflatable nylon dome built on the UAF campus that was used for hockey in the winter and tennis in the summer.

File: UAF-2015-126-69 Collection: Russell Knapp Papers.

Alaska and Polar Regions Collections, Elmer E. Rasmuson Library, University of Alaska Fairbanks.

With the new facility, the university could enter collegiate basketball in a serious fashion. University President William R. Wood, a former professional player, backed the effort enthusiastically and attended most home games. In 1972-1973, the team won the regional NAIA championship.

The rifle teams, already top-ranked shooters, used their new range to hone skills that have earned 10 national championships.

Six years after the Patty Center was completed, the university installed an inflatable nylon dome over a hockey rink next to the center. Students named it the Beluga, after the white whale. The university fought wind, snow and vandals to keep it inflated for the next 15 years before scrapping the idea. The indoor ice arena was built in 1979, and by 1985 the Nanooks hockey team had become a NCAA Division I team.

The university served as an evacuation site and emergency shelter for the more than 7,000 men, women and children relocated from downtown Fairbanks when the Chena River swelled over its banks and caused massive flooding in August 1967. The heat and power plant, critical to keeping everyone fed and warm, nearly succumbed, but volunteers built a sandbag wall that helped save it.

Heavy rains in the high country east of Fairbanks sent a vast flood down the Chena River. Much of downtown Fairbanks sat under six feet of water on Aug. 15.

As the flood grew, UA President Wood opened the campus to all refugees. About 7,000 arrived, first in vehicles but then by boat and helicopter as the water rose up to the base of the hill.

The huge crowd needed food, water and warmth. Providing it depended on the university’s heat and power plant, located at the foot of the hill, within reach of the floodwaters. Bulldozers started building a dike, but they weren’t fast enough. So the university used KUAC and the public address system to ask for volunteers at the power plant to build a sandbag wall.

“I’ve never seen anything like it. They started coming over that hill like caribou – men, women and children,” plant supervisor Gerald England recalled later.

Power plant workers discovered water shooting up from wells inside the plant’s utilidor. So, with pumps supplied by the Army, they started moving water out into the diked area. But that threatened to flood the coal delivery grate, so the Army delivered more pumps and they were used to move the water over the sandbag wall. The power plant was saved with only inches to spare. Classes opened on schedule in early September.

“The water in the power plant basement rose to within 6 inches of flooding electric pumps vital to the operation of the boilers. Had the water gone that much farther, we would have lost. This condition went on for more than 72 hours when the floodwaters finally began to abate. Except for the volunteers filling and stacking sandbags, not many people found out how close to real disaster we came.”

–Ernest Kaiser, student and power plant employee, in the fall 2014 issue of Aurora magazine

Film provided by Alaska Film Archives YouTube a unit of the Alaska and Polar Regions Department in the Elmer E. Rasmuson Library.

Film provided by Alaska Film Archives YouTube a unit of the Alaska and Polar Regions Department in the Elmer E. Rasmuson Library.

Film provided by Alaska Film Archives YouTube a unit of the Alaska and Polar Regions Department in the Elmer E. Rasmuson Library.

Film provided by Alaska Film Archives YouTube a unit of the Alaska and Polar Regions Department in the Elmer E. Rasmuson Library.

Taking advantage of scientific and military interest in the workings of the Earth’s upper atmosphere and the aurora, a small group of employees at the Geophysical Institute created the world’s only university-owned rocket range 30 miles north of Fairbanks.

When Neil Davis went to NASA’s Goddard Space Center on a fellowship in 1962, he had the general idea that he wanted to study the aurora by flying rockets into it. Seven years later, he watched the first rocket launched from Poker Flat Research Range north of Fairbanks do just that.

Davis, who grew up on a homestead southeast of Fairbanks, earned a doctorate in geophysics at the University of Alaska a year before going to Goddard. While there, he worked on launching instrument-tipped rockets from an ocean-going ship into the ionosphere to study magnetic fields. He also worked with some highly sensitive television equipment that turned out to be great for capturing images of the aurora in Canada.

After returning to Fairbanks in 1965 with a position at the Geophysical Institute, Davis secured money from NASA and the National Science Foundation to continue both his rocket and television work. He and others at the Geophysical Institute decided it would be useful to have a place in Alaska to launch the rockets.

They talked the Fairbanks North Star Borough into leasing six square miles of land along the Steese Highway 30 miles north of Fairbanks where the road first parallels the Chatanika River. So, by 1966, the range existed, but only on paper.

By virtue of accident, literally, the U.S. military turned its interest to Fairbanks two years later. The crash of a B-52 bomber carrying nuclear bombs at Thule, Greenland, prompted Denmark to bar continuation of certain U.S. military work there. The military decided to send one of the banned projects, designed to help understand the potential effects of a nuclear blast on ionosphere, to the Geophysical Institute’s range in Fairbanks.

But there was no rocket range yet, so Davis and others at the institute got to work on the range that summer. They cobbled much of it together using surplus equipment and materials, including some obsolete 33-kilovolt transformers found at Fort Wainwright’s salvage yard.

The first rocket went up from Poker Flat on March 5, 1969, followed by several more in short order. The rockets released barium to create green and red artificial auroras visible across Alaska. About 60 volunteers took pictures from around the state and western Canada.

The military viewed it as a one-time deal, but Davis and others at the university did not. Launches at the world’s only university-owned rocket range have continued ever since. On March 15, 2005, Poker Flat launched its 300th major rocket.

“… The proposed launch site was near where Poker Creek came down out of the hills to join the Chatanika River. … The name Poker Flat was a bit reminiscent of Yucca Flat and Frenchman Flat, portions of the Nevada Test Site … Figuring in also was the title of Bret Harte’s story, ‘The Outcasts of Poker Flat,’ a title I thought had a nice ring to it. So sort of as a multi-pronged joke, I called the place Poker Flat, with the idea that this name would suffice until a more appropriate one came to mind, but one never did so the name stuck.”

– Neil Davis, in “Rockets Over Alaska,” his history of the Poker Flat Research Range

“The resulting space spectaculars are like northern lights in the Arctic skies – in glowing, shimmering colors blended by man. Proud Alaskans turn out like space-watchers at Cape Kennedy to see the show. Perhaps most remarkable of all is that the feat has been accomplished at a home-made rocket range assembled mostly of scrap materials scrounged by the institute.”

–A story in The Seattle Times by reporter Stanton Patty, who also was the son of former UA President Ernest Patty

Strict rules, especially for women, had existed on campus since the college began. But cultural changes in the 1960s eroded most of the restrictions, and the mandatory hours for women in dorms ended in fall 1971.

A list published in the university’s catalogs in its earliest years laid out the standards that President Charles Bunnell and his faculty expected dormitory residents to follow. Men had to turn out their lights between 11:30 p.m. and 5 a.m. Their rooms could be inspected “periodically by the proctor.” Freshmen could go to Fairbanks only on Friday and Saturday nights.

The list for women was nearly twice the length of the one for men.

“Permission must be secured from the office of the dormitory for car riding,” read one rule for the women.

“Each girl shall be permitted two one o’clock date nights a month on Saturday night,” read another. “On every other night she must be in the dormitory by 11 o’clock.” Women had to sign in and out of the dorms, even to visit other buildings on campus.

The rules gradually relaxed during the following decades. Moore Hall opened as a co-ed dorm in 1966. Senior women with a GPA above 2.5 were excused from the 11 p.m. curfew that year. The curfews for all women living in the dorms ended in 1971.

President Patty’s campuswide ban on alcohol, first imposed in 1956, ended in 1972. By then it was widely, if privately, ignored.

The Pub opened at Wood Center in 1975.

“We’re not interested in a student’s personal behavior in his own room, until it infringes on other persons’ rights.”

–Harris Shelton, head of student housing, quoted in The Polar Star, Nov. 26, 1971

President Robert Hiatt, who succeeded Wood, announced that the university would be reorganized into three main campuses led by chancellors, with a separate branch for community colleges. A statewide administration in Fairbanks would oversee it all.

The University of Alaska Fairbanks began with the appointment of its first chancellor, Howard Cutler, in 1975.

University campuses in Anchorage and Juneau, which had started as community colleges but had expanded some offerings into four-year programs, also received their own chancellors. A statewide administration in Fairbanks retained overall authority over the universities and a community college branch.

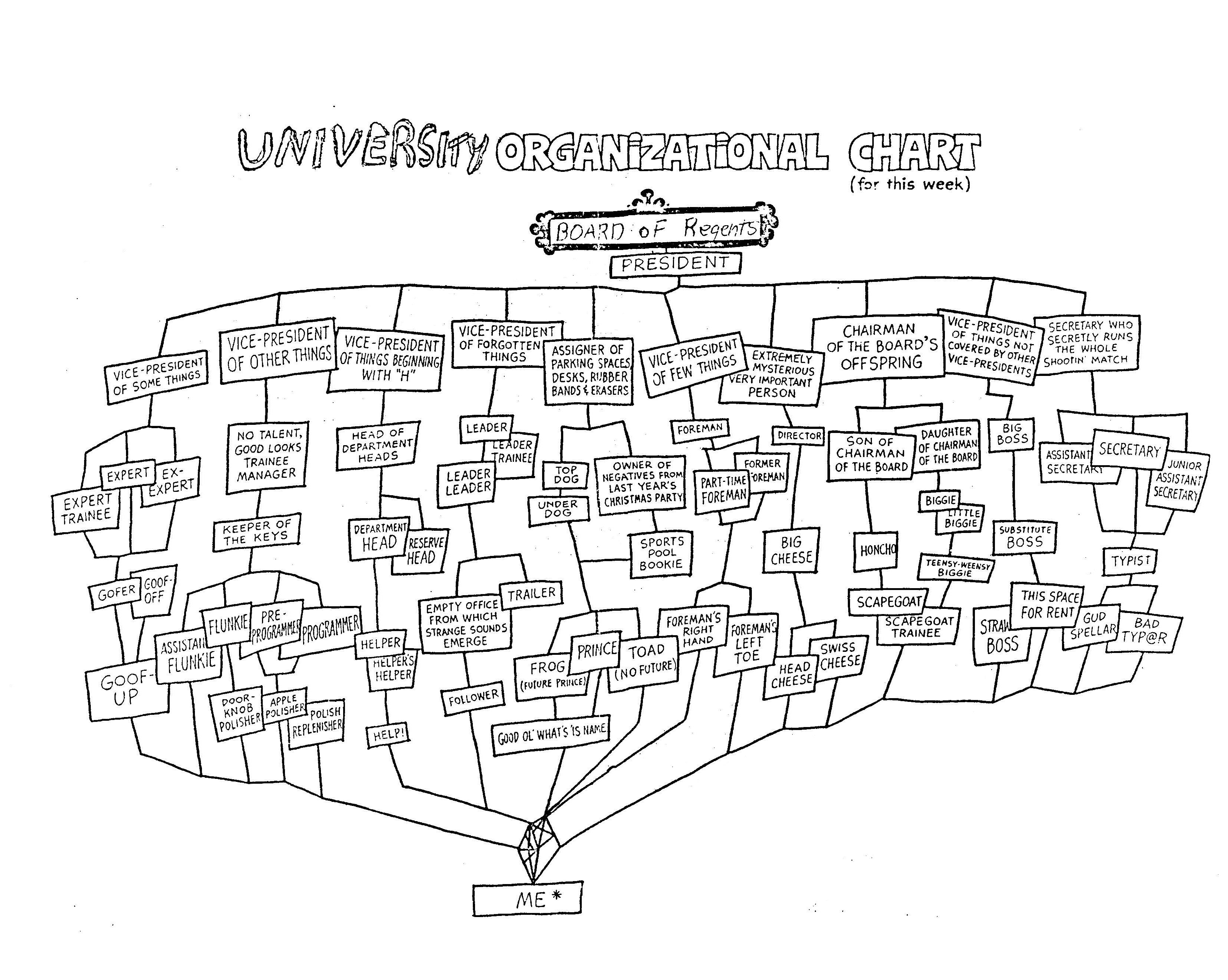

The reorganization came in the midst of much turmoil within the institutions, and the changes didn’t resolve the strife. Multiple statewide organization charts were drawn up by administrators from the early to mid-1970s; some were approved, many were not.

Hiatt resigned in 1977 after the university announced it had a $10 million deficit and needed a bailout from the state. He was followed by four presidents or acting presidents in short succession.

While the basic three-campus structure has continued through the present, the relationship of community colleges, particularly in Anchorage and Juneau, remained in flux well into the 1980s.

UAF’s first formal name contained a comma; it was the “University of Alaska, Fairbanks.” The comma changed to a hyphen in 1981. The hyphen was dropped in 1987.

“From 1972 through 1977 the university experienced more expansions, more problems, more conflicts, and more threats to their existence than ever before. Reorganizations had solved few, if any, of their difficulties but would continue to be the solution of choice in the following years of strife and upheaval.”

– Kathleen Stewart, “Chronology of Organizational Structure Changes in a Community College” 1984 master’s thesis, Alaska Pacific University

The University of Alaska revised its organizational chart multiple times during the 1970s, provoking an anonymous cartoonist to offer this humorous take on the institution's structure.

Source: "Chronology of Organizational Structure Changes in a Community College," a master's thesis by Kathleen Stewart, Alaska Pacific University, 1984