Minimal Strings

by Catherine Madsen

The Nunamiut, the Iñupiat of the area around Anaktuvuk Pass, at one point played a

small instrument about 16 inches long; it was held upright along the player’s left

side and had one string, which was beaten with a small hammer. According to Helge

Ingstad (a Norwegian explorer who lived with the Nunamiut in 1949-50) it was called

the kasagnaujaq; he included a sketch of it in his book Nunamiut: Among Alaska’s Inland Eskimos. The online Iñupiaq dictionary spells it kasaŋnauraq and calls it the Iñupiaq banjo. Other than those two sources, I’ve found no other

reference to the instrument. Maybe someone who’s reading this has seen or played one.

The Nunamiut, the Iñupiat of the area around Anaktuvuk Pass, at one point played a

small instrument about 16 inches long; it was held upright along the player’s left

side and had one string, which was beaten with a small hammer. According to Helge

Ingstad (a Norwegian explorer who lived with the Nunamiut in 1949-50) it was called

the kasagnaujaq; he included a sketch of it in his book Nunamiut: Among Alaska’s Inland Eskimos. The online Iñupiaq dictionary spells it kasaŋnauraq and calls it the Iñupiaq banjo. Other than those two sources, I’ve found no other

reference to the instrument. Maybe someone who’s reading this has seen or played one.

Many cultures around the world developed one-stringed instruments, perhaps when bow hunters began idly tapping on their bowstrings with an arrow and discovered they could vary the pitch. Kouame Sereba, who was born in the Ivory Coast but moved to Norway in his twenties and has worked with many leading Norwegian musicians, plays a mouth bow solo here. But even limiting the search to instruments that originated in the circumpolar North, we find a fair number with one to three strings. Some have fallen out of use altogether; some are being revived by folk musicians, historic instrument enthusiasts, and Viking reenactors.

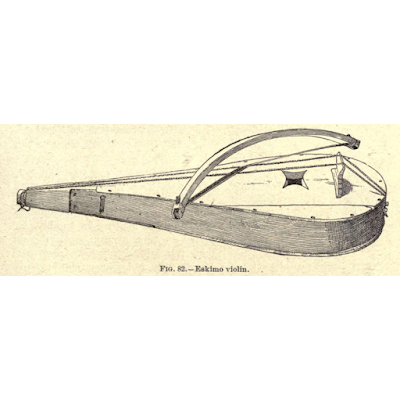

The Tautirut or Inuit fiddle, generally with two or three strings, is (or was) held on the lap and played with a bow. An example is heard starting at 1:02 here. Since the tautirut has been found only in the Hudson Bay area, one theory holds that it was introduced by sailors from Orkney and Shetland; it does have a resemblance to the (now virtually extinct) Shetland gue . But it’s not impossible that the instrument predates European contact.

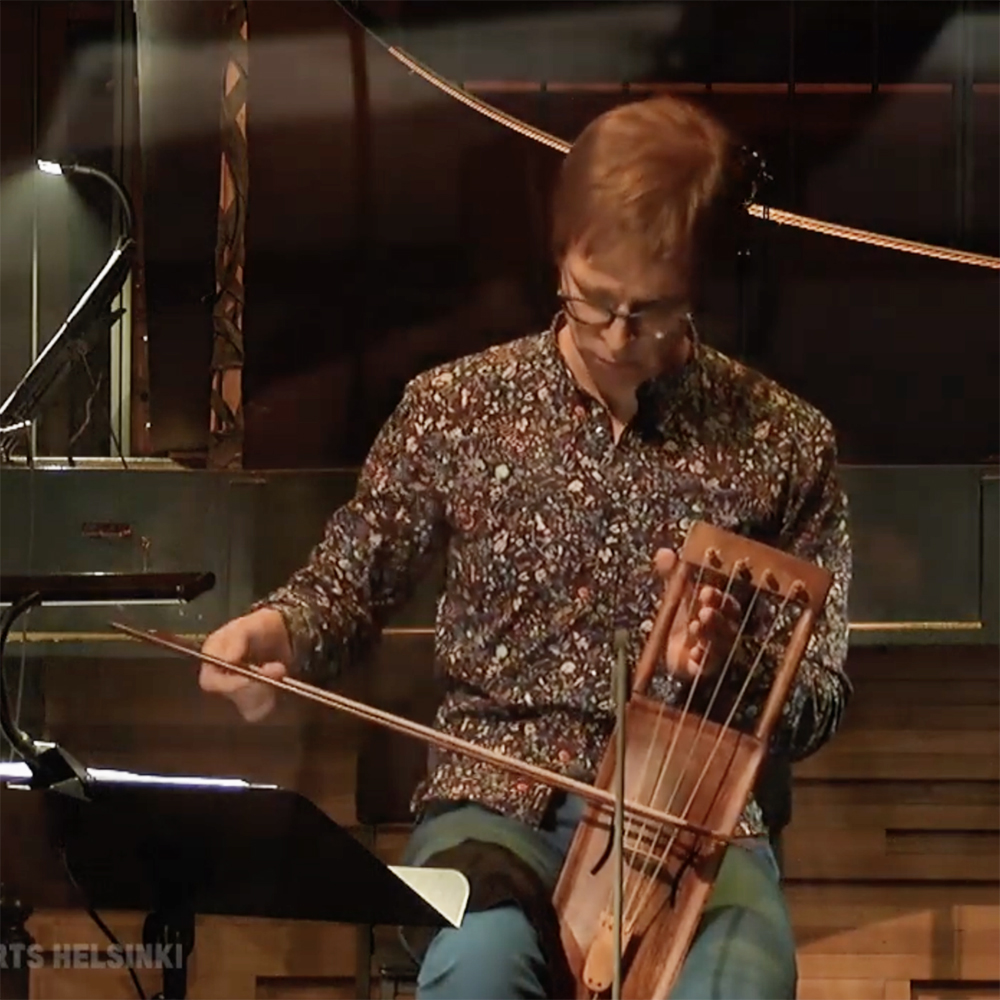

The Scandinavian talharpa or tagelharpa and the Finnish jouhikko —essentially the same instrument by two different names—are closely related to the Shetland gue, and are among the instruments enjoying a revival. Like the gue, they are bowed. They do not have fingerboards, so the melody is created by the fingers touching the strings in mid-air. Pekko Käppi demonstrates traditional Finnish and Estonian scales, straight and syncopated bowing styles, and his preferred tuning in this engagingly informal jouhikko tutorial. And the jouhikko isn’t only a solo instrument, as shown by this duet between Lassi Logrén and Ilkka Heinonen.

Scandinavia also produced the psalmodikon, which has a fretboard and is played horizontally like a one-stringed dulcimer. It can be either bowed or plucked. Developed in the early 19th century from the ancient monochord, the psalmodikon was used to teach hymns in schools, and in churches too poor to afford an organ—largely because it was unthinkable that a fiddle (a dance instrument, therefore the devil’s instrument) should be used for the purpose. However, if the devil can quote scripture to his own purpose, he also has the option to take over the psalmodikon once in a while—check out Magnus Högman’s Psalmodikon Viking Blues.

Iceland has two folk instruments: the fiðla, a box with as few as two strings or as many as six, is laid on a table and bowed, with the melody fingers touching the strings in mid-air. The langspil generally has one fretted melody string and one or two drone strings, and may be either bowed or struck with sticks. This fascinating 2012 thesis by Hildur Heimisdóttir discusses the history of the fiðla and the langspil, and the social attitudes toward them in a country whose vulnerability to natural disasters kept it impoverished and culturally underdeveloped from the time of the sagas to the era of the Second World War.

The langeleik, a popular Norwegian folk instrument similar to the langspil, has one fretted melody string and multiple drone strings, and is plucked with a plectrum. See it played in a variety of styles here (don’t miss the dancing horse, starting at about 6:30).

The moral of the tale? The human musical instinct is alert to all opportunities, impossible to discourage, and can do a lot with a little.

Resources

Click the links below to learn more about the performers and shops mentioned in the article.

About the Author

Catherine Madsen is a writer, singer and folk harper now living in Michigan. The three years she spent in Fairbanks as a child (1962-65) were a turning point in her life, and she established the Circumpolar Music Series as a gift of gratitude.