Alaska megastorms vs. East Coast hurricanes

Ned Rozell

907-474-7468

Sept. 29, 2022

“Hurricane Hal” Needham smiles on a benign day on a Galveston, Texas, beach. The extreme weather and disaster scientist for CNC Catastrophe & National Claims recently drove to a parking garage in southwest Florida to document Hurricane Ian.

My friend Hal called the other day from a parking garage in Punta Gorda, Florida. In his car he had nine one-gallon jugs of water, a red-plastic container of gasoline and a motorcycle helmet.

Hal, a former Alaskan, is a hurricane expert living in Galveston, Texas. He sometimes plants himself in vulnerable places and sends storm updates to his Twitter and Facebook followers.

Hal parked his car on the third level of a concrete parking garage — his favorite wind-and-storm-surge-resistant shelter during these events. Hurricane Ian was then rotating toward Hal and millions of others on the west coast of Florida.

Last week, before he knew he’d be driving toward southwest Florida, Hal expressed to me a wish that he could have flown right then to the west coast of Alaska. He wanted to observe the effects of the major storm named Merbok, a typhoon that morphed into something bigger.

A typhoon is a hurricane that forms over the western Pacific Ocean. Both hurricane and typhoon refer to a mass of clouds and thunderstorms rotating above tropical or subtropical waters.

Unlike the giant storm that hit Alaska in mid-September, hurricanes and typhoons both have eyes — calm circular areas in the center of clouds that are rotating because of the friction caused by a spinning planet.

Merbok (the Malaysian name of a spotted-neck dove that researchers with the Japanese Meteorological Agency bestowed on the storm) had its own eye when it sprang to life as a typhoon in the Pacific Ocean west of Wake Island.

Merbok then grew into an eyeless monster as it drifted out of tropical latitudes. It was no longer a typhoon by the time it crossed onto the Bering Sea near the Aleutian island of Shemya, said University of Alaska Fairbanks climate specialist Rick Thoman.

Instead of feeding off warm ocean, the growing storm fed off air-temperature differences and developing cold and warm fronts.

“That transition meant Merbok was much larger in size in the Bering Sea than it was as a typhoon,” Thoman said.

He explained: “Shortly before transition, Typhoon Merbok had storm-force winds extending about 100 miles southeast of the center. In contrast, as ex-Merbok passed west of the Pribilof (islands), the storm-force winds extended 300 miles southeast of the center.

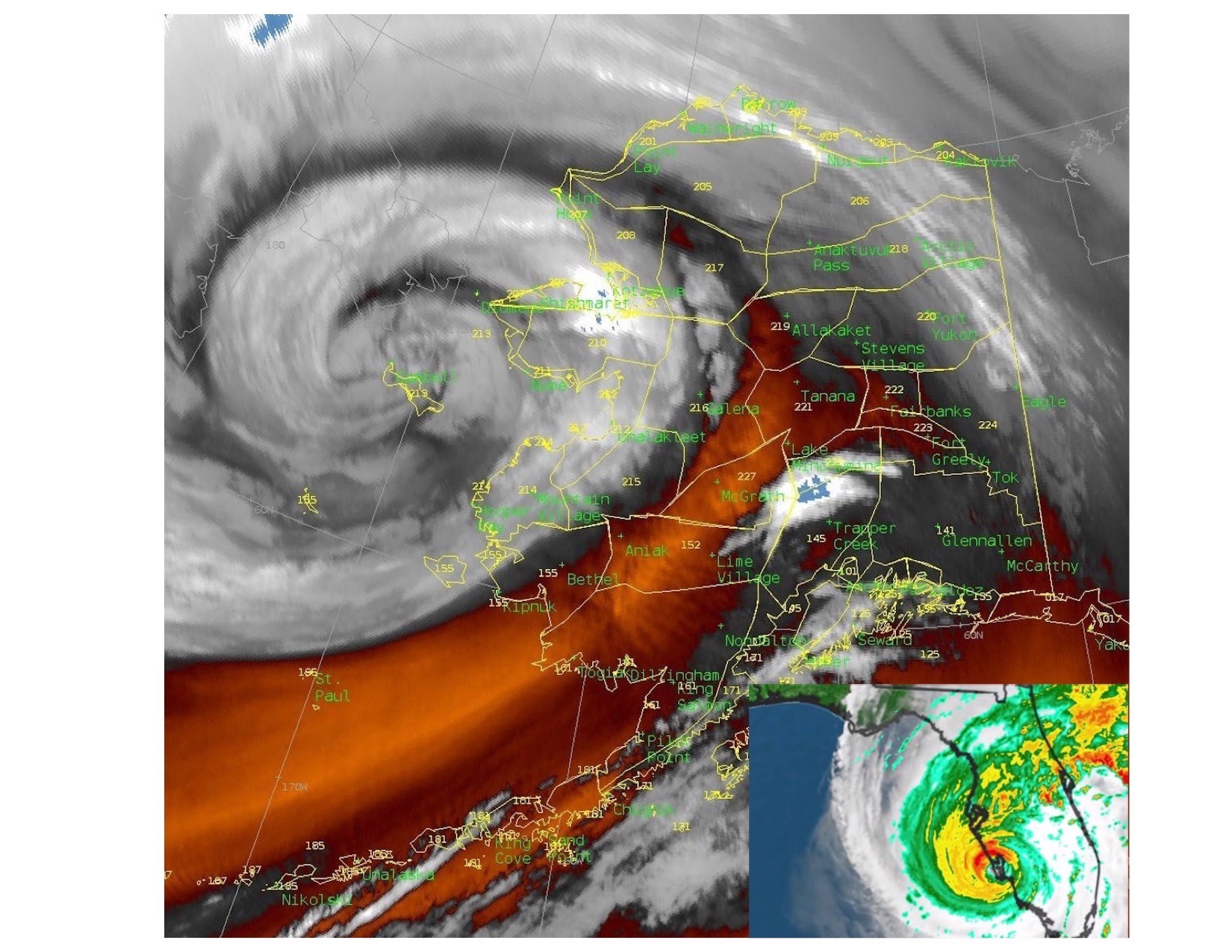

Images show the storm named Merbok as it encountered the western Alaska coast on Sept. 17, 2022, compared to Hurricane Ian as it bore down on Florida on Sept. 28, 2022. Both states are sized to scale.

“This huge wind field acted as a plow pushing water north and eastward until it ran into the Alaska coast,” Thoman said.

The storm impacted a great swath of Alaska, from just north of Bristol Bay to north of Bering Strait, flooding low portions of villages and many fishing and hunting camps along miles and miles of coastline.

That’s a big deal, Thoman wrote in a piece for The Conversation.

“Winter is coming, and the time when it’s feasible to make repairs is running short. This is also the middle of hunting season, which in western Alaska is not recreation — it’s how you feed your family.”

Less than two weeks later, as far in America as you can get from Alaska, Hurricane Ian was pounding southwest Florida. Hal, leaning out of the parking garage, measured 100 mile-per-hour winds. He was also wondering if he should pull on his motorcycle helmet for protection from flying things.

Since the late 1970s, the University of Alaska Fairbanks Geophysical Institute has provided this column free in cooperation with the UAF research community. Ned Rozell is a science writer for the Geophysical Institute.