Out of the office and up Denali!

July 2004

By Amy Hartley, Geophysical Institute

Installing a weather station at 19,000 feet is rough duty, but two men from UAF recently

left their offices on campus to climb almost to the top of North America's highest

peak and get the job done.

Installing a weather station at 19,000 feet is rough duty, but two men from UAF recently

left their offices on campus to climb almost to the top of North America's highest

peak and get the job done.

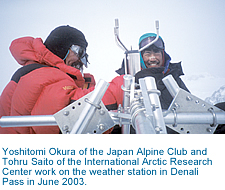

Kevin Abnett, a software engineer from the university's Geophysical Institute, and Tohru Saito of the International Arctic Research Center, scaled Denali--the traditional Athabascan Indian name for Mount McKinley. They were out for 20 days as they hauled and then installed 20 pounds of equipment at an outcrop just south of the peak's summit. The weather station--an upgrade and replacement for one installed earlier which malfunctioned and was no longer transmitting data--will record wind speed and direction, relative humidity, barometric pressure and temperature.

For Abnett, the opportunity to climb Denali allowed him to witness first-hand the

extreme weather conditions his equipment is expected to withstand. During storms the

winds on the mountain are typically greater than 100 miles per hour with winter temperatures

as low as 60 degrees below zero Fahrenheit. The weather station recorded an unofficial

wind speed of 188 miles per hour three days before it stopped working in January 2003.

For Abnett, the opportunity to climb Denali allowed him to witness first-hand the

extreme weather conditions his equipment is expected to withstand. During storms the

winds on the mountain are typically greater than 100 miles per hour with winter temperatures

as low as 60 degrees below zero Fahrenheit. The weather station recorded an unofficial

wind speed of 188 miles per hour three days before it stopped working in January 2003.

"In 2002, when I first got the invitation to go, I said, 'No--absolutely not! I prefer oxygen in the air I breathe!'" Abnett said. "It sounded so ridiculous to me at the time, I declined. But as I started to think about it more, I realized I wanted to understand the conditions on the mountain better, so I decided to make the attempt this summer."

For months, Abnett trained for the climb. He hiked the Fairbanks area with a large

pack and took a mountaineering class. He was in good physical condition, but before

leaving he was understandably anxious.

For months, Abnett trained for the climb. He hiked the Fairbanks area with a large

pack and took a mountaineering class. He was in good physical condition, but before

leaving he was understandably anxious.

"The physical endurance required at altitude was the most challenging," Abnett said. "I just couldn't seem to get enough air in my lungs, especially carrying a 40-pound load. No matter how hard I breathed, it just wasn't enough. After a few days of acclimatizing it was better, but still difficult."

This was the third trip up Denali for Saito. He's worked on the weather station project

since 2002, when the first equipment which transmitted data was built and installed.

From his cubicle in the International Arctic Research Center, Saito helped coordinate

the trip's logistics and translated for participants from Alaska and Japan. Saito's

involvement was crucial because the expedition was led by Japanese mountaineer Yoshitomi

Okura and aided by members of the Japan Alpine Club.

This was the third trip up Denali for Saito. He's worked on the weather station project

since 2002, when the first equipment which transmitted data was built and installed.

From his cubicle in the International Arctic Research Center, Saito helped coordinate

the trip's logistics and translated for participants from Alaska and Japan. Saito's

involvement was crucial because the expedition was led by Japanese mountaineer Yoshitomi

Okura and aided by members of the Japan Alpine Club.

Having been up the mountain before, Saito was supportive of Abnett. He and Abnett hiked together and practiced rope-climbing, and he explained what Abnett could expect.

"Getting to know someone before you go is important," Saito said. "When you're doing something like this, it's you against the mountain. It's you against all those elements, so it's nice to have someone you know there to help you."

"The Japanese climbers were just great," Abnett said. "They helped me out many times on my way up there."

Abnett set the weather station equipment up at the 14,000 foot medical camp on June 22, 2004 and ran some tests. On June 27 the Japanese crew climbed to 18,735 feet and assembled the equipment at its permanent location, then continued to the summit. The whole team was down at Kahiltna Base Camp by June 30, when more tests confirmed the weather station was transmitting as intended.

"We're receiving the signal just fine in Fairbanks now," Abnett said.

Daily updates on progress of the climbers were posted at www.iarc.uaf.edu/mt_mckinley.php (Bad URL kept for historical reasons)

Weather data for everyone

The Mount McKinley weather station project got Abnett and Saito off campus and into

the extreme, but the crux of the project is to provide critical information about

a location that is little known or understood. The UAF team hopes to enhance current

forecasting methods atop the mountain with this station, which will provide current

weather data by sending a transmission with the latest information back to the International

Arctic Research Center every 30 minutes. The data will also be listed online around

the first of August, so anyone in the world can key in its address and find out what's

happening atop Denali. The Mount McKinley weather station website is www.iarc.uaf.edu/mt_mckinley_weather.php

(Bad URL kept for historical reasons).

Related stories

- Alaska Science Forum, May 27, 2004 Research team heads back to Denali's shoulder

- Alaska Science Forum, July 10, 2003 Mountaineering and science meet on Mount McKinley

- Alaska Science Forum, September 29, 1999 Denali weather, courtesy of Naomi Uemura

- Denali National Park general information

- Mountaineering in Denali National Park

Body photo credits: Photo by Amy Hartley, photo by Ned Rozell.

Sidebar photo credits: Top photo © Chris LeDoux, other photos by Ned Rozell.

The peak of Mount McKinley glows in the morning sunlight in early November.

Denali's 14,000-foot "medical camp," where climbers stay for several days to acclimate to high altitude before climbing onto Denali's West Buttress.

Mount Hunter, 14,573 feet, as seen from Denali's 14,000-foot camp.

Mount Foraker, 17,400 feet, as seen from Denali's 14,000-foot camp.

Tohru Saito of the International Arctic Research Center at Denali's "Motorcycle Hill" camp at about 11,000 feet.