UAF students explore Mars

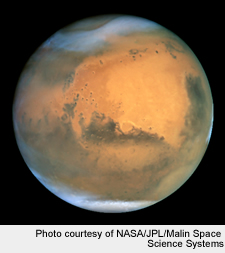

Frosty white water ice clouds and swirling orange dust storms above a vivid rusty

landscape reveal Mars as a dynamic planet in this sharpest view ever obtained by an

Earth-based telescope. This image was captured by the Hubble telescope.

Professor Buck Sharpton, president's professor of remote sensing and an image of the

terrain of Mars.

Robbie Herrick (center), a research associate professor with the Geophysical Institute,

meets with graduate students enrolled in the planetary science program.

Sharon Pitiss, a graduate student pursuing a master's degree in geology, studies satellite

images.

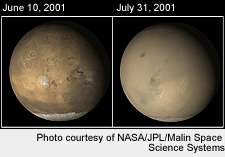

Late in June 2001, as the Mars southern winter transitioned to spring, dust storm

activity began to pick up as cold air from the south polar cap moved northward toward

the warmer air at the martian equator. This image was taken by one of the wide angle

cameras on the Mars Orbiter Camera system onboard the Mars Global Surveyor.

Video: MER Entry, Descent and Landing on Mars

Video: Exploring the martian terrain.

Fred Calef, a Ph.D. candidate in geology, takes a break in his office. Calef has been

with the planetary sciences program since 2001.

Scientists working with NASA's Mars Exploration Rover Spirit decided to examine this rock, dubbed Wishstone. Spirit used its rock abrasion tool first to scour a patch of the rock's surface with a wire

brush, then to grind away the surface to reveal interior material. Spirit used its panoramic camera during the rover's 342nd day on Mars to take the three

individual images that were combined to produce this false-color view emphasizing

the freshly ground dust around the hole cut by the rock abrasion tool.

Roman Krochuk, a Ph.D. candidate in geology and a member of the planetary sciences

group, relaxes near one of the microscopes in the planetary sciences lab. Krochuk

uses the microscope to examine rocks from meteorite impact craters.

By Casey Grove, Sun Star and Amy Hartley, Geophysical Institute

February 2005

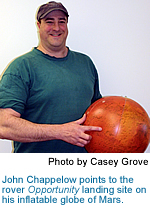

In a dimly lit office in the West Ridge Research Building, John Chappelow sits at

his computer analyzing data. A poster of the Red Planet's pockmarked landscape hangs

behind him, while a screensaver of martian terrain occasionally blips into a slow

pan across his computer screen.

In a dimly lit office in the West Ridge Research Building, John Chappelow sits at

his computer analyzing data. A poster of the Red Planet's pockmarked landscape hangs

behind him, while a screensaver of martian terrain occasionally blips into a slow

pan across his computer screen.

Chappelow, a research assistant and graduate student, is usually at his desk in Fairbanks, but investigating the terrain of Mars. Students in the Geophysical Institute's planetary science group spend as much time on other planets as human beings possibly can from 60 million miles away.

ñUnless my advisor decides to send me to Mars, I can't do any field work, but if I

can understand what's happening here in Alaska, I can get an idea of the processes

at work on other planets," he said.

ñUnless my advisor decides to send me to Mars, I can't do any field work, but if I

can understand what's happening here in Alaska, I can get an idea of the processes

at work on other planets," he said.

Chappelow is one of a handful of students making correlations between the Alaska landscape and those of other planets while working on graduate degrees within the Department of Geology and Geophysics at the University of Alaska Fairbanks. The planet Mars dominates the students' research due to its similarities to Earth--like the Arctic, the martian landscape is riddled with permafrost.

"One benefit of working in the Arctic is that it is very cold and dry, much like Mars,"

said Buck Sharpton, president's professor of remote sensing. Sharpton and Associate

Research Professor Robbie Herrick serve as faculty members for the planetary sciences

group. "Alaska is a good site for testing equipment and designing exploration strategies.

We can study processes that occur here that also occur on Mars."

"One benefit of working in the Arctic is that it is very cold and dry, much like Mars,"

said Buck Sharpton, president's professor of remote sensing. Sharpton and Associate

Research Professor Robbie Herrick serve as faculty members for the planetary sciences

group. "Alaska is a good site for testing equipment and designing exploration strategies.

We can study processes that occur here that also occur on Mars."

Herrick joined the Geophysical Institute in 2004, after 10 years as a staff scientist at the Lunar and Planetary Institute in Houston, Texas. Sharpton says the addition of Herrick provided the nascent program a needed boost. Herrick lends his expertise on impact craters and works with data from NASA's unmanned missions to sites throughout the solar system.

Making comparisons between the landscape of the Arctic and that of Mars is a much cheaper approach to space exploration. To study these parallels requires a diverse scientific background, one that calls for a solid command of the fundamentals.

"Students must be well rounded in physics, chemistry and math, but they also have to have this artistic eye that can interpret maps and landforms," Sharpton said. "In planetary sciences, we're combining the theoretical with empirical data."

Chappelow's research focuses on impact craters. He's come up with a new approach to

understanding crater characteristics called impact crater morphometry. He's using

it to better understand the shape of craters on Mars and the way they were formed.

Chappelow's research focuses on impact craters. He's come up with a new approach to

understanding crater characteristics called impact crater morphometry. He's using

it to better understand the shape of craters on Mars and the way they were formed.

Chappelow isn't the only student poring over thousands of images of Mars' surface. Students Katie Hessen and Sharon Pitiss, both pursuing master's degrees in geophysics, are studying the topography and statistics of impact craters on Mars. Pitiss uses the information she gathers to piece together the origin and evolution of Mars' hematite region, Sinus Meridiani.

Understanding Mars' topography is also the interest of Ph.D. candidate Fred Calef. Calef's background in geology aids his studies of the Red Planet's topography, but craters aren't his only interest. His research also focuses on the ice-related features of the planet and is aided by images gathered by Spirit and Opportunity, two rovers NASA landed on Mars in January 2004 that continue to gather data as they roam the martian landscape.

Calef says the rovers are a tremendous help to planetary scientists, but a good foundation in our own planet's geology is key to understanding our next-door neighbor in the solar system.

"You need to know what Earth is like before you can start studying other planets,"

Calef said. "The rovers are great, but they still can't do what a geologist on the

ground could."

"You need to know what Earth is like before you can start studying other planets,"

Calef said. "The rovers are great, but they still can't do what a geologist on the

ground could."

Until a manned mission to Mars is planned, the graduate students in the planetary science project can only do the next best thing: study the planet by comparing it to something they're very familiar with--the Alaska landscape.

Six students are currently working on graduate degrees with an emphasis on planetary science within the Department of Geology and Geophysics. Sharpton says the group's modest size works to its benefit.

"A small program like ours allows for close contact with students, and we're tightly focused," he said.

"I like being part of a small group," said Chappelow. "I have a lot of latitude here.

I'm fairly independent, but if I need to, I can just walk down the hall to talk to

my advisor."

"I like being part of a small group," said Chappelow. "I have a lot of latitude here.

I'm fairly independent, but if I need to, I can just walk down the hall to talk to

my advisor."

With the success of NASA's two rovers on Mars, interest in the Red Planet is growing. Sharpton believes the recent explosion of new pictures and data from the planet may spur more students to pursue studies in planetary sciences.

"This is a very captivating subject area. Kids seem to drop their video games and begin paying attention when it comes to space," he said. "In terms of motivating kids, studies in planetary sciences are hard to beat."

For more information, please contact:

- Amy Hartley, Geophysical Institute at (907) 474-5823 or amy.hartley@gi.alaska.edu.