Glaciologists anticipate massive ice shelf collapse

February 3, 2016

Meghan Murphy

907-474-7541

A team of researchers is traveling to a rocky outcrop in Antarctica to study a massive ice shelf that could crash down around them before the end of March.

University of Alaska Fairbanks glaciologist Erin Pettit said that an ice shelf about 1,000 feet thick and a third the size of Rhode Island is on the verge of shattering into millions of icebergs during February or March, the end of Antarctica’s summer. If it does, the lead researcher and her team will be within viewing distance in a place they hope doesn’t live up to its name — Cape Disappointment.

Pettit, an associate professor in the Department of Geosciences, said studying ice shelves nearing disintegration is necessary because the climate is rapidly changing in Antarctica and Greenland and melting ice caps contribute to changes in sea level. The question is no longer if sea level is going to rise; the questions are how much and how soon.

“In trying to figure out the ‘how soon,’ we need to find out the triggers that make these ice shelves go,” she said. “We know the warmer ocean melts them from underneath, and the warmer air melts them from the top. As this happens, they become thin and weak. But something pushes them over the edge to catastrophic collapse. What is it?”

Accompanying Pettit to Antarctica is Ted Scambos, a senior research scientist at the National Snow and Ice Data Center at the University of Colorado Boulder, and Christina Carr, a graduate student in UAF’s Department of Geosciences. A mountaineer from the British Antarctic Survey will help them navigate. Martin Truffer, a glaciologist with UAF’s Geophysical Institute, is a research member on the project, but he just returned from Antarctica and will support the team from Fairbanks.

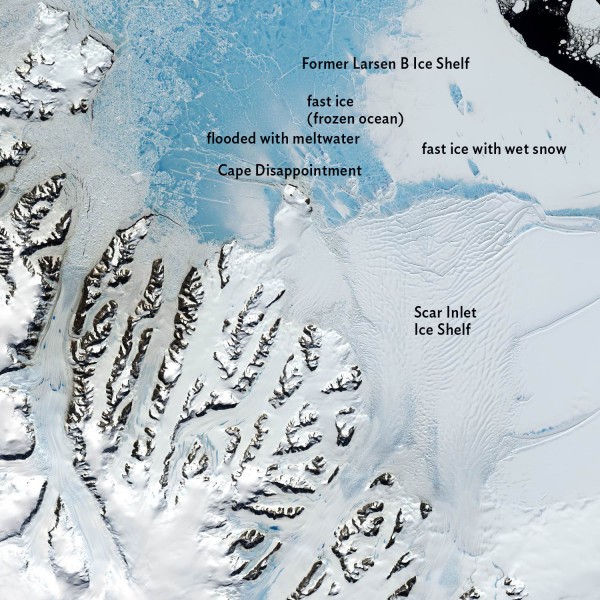

Through a National Science Foundation grant, the researchers are collecting data on an ice shelf that was once part of a larger one known as Larsen B. It is located on the Antarctic Peninsula, which is the northernmost point of the vast frozen continent. In 2002, satellite images revealed that much of the ice shelf had disappeared, leaving behind a remnant in a sheltered bay called Scar Inlet.

Their study is part of a broader one looking into how and why ice shelves are disintegrating along the coast of Antarctica, a phenomenon that increased dramatically starting in the early 1990s and is linked to a warming climate in Antarctica.

These ice shelves form over thousands of years as ice sheets and glaciers flow off the land and extend onto the ocean to create thick floating platforms of ice. They act as dams, holding back glaciers. When they disintegrate, they unleash the glaciers and release ice at increasing rates into the ocean, which contributes to rising sea level.

Scambos said the Scar Inlet ice shelf has been showing signs of increased melting and large-scale fracturing over the past 14 years. The only support holding back more fracturing could be the 6 to 10 feet of frozen ocean in front of it — a thin, fragile crust compared to the ice shelf plate.

“Since late 2011, the larger bay where the Larsen B once resided has been covered with a solid sheet of frozen ocean ice, called ‘fast ice’ because it is ‘fastened’ or frozen to the coastline,” Scambos said. “We suspect this ice is supporting the weakened Scar Inlet ice shelf and that the shelf is poised to break up if the thin fast ice breaks away. One good windstorm could set some of this process in motion.”

Even if the ice shelf doesn’t collapse, the research mission will be a success.

"This will be the first time anybody records ground-based data from an ice shelf that is ready to break up,” Truffer said. “The prize, of course, would be to witness the actual break-up, but, even if we miss that, we will have a detailed record of ongoing weakening of the shelf."

ADDITIONAL CONTACTS: Martin Truffer, glaciologist with the University of Alaska Fairbanks Geophysical Institute and professor of physics, 907-474-5359, truffer@gi.alaska.edu; Jane Beitler, science communications manager, National Snow and Ice Data Center, CIRES/University of Colorado, 303-492-1497, press@nsidc.org

Follow their expedition online: https://iceshelf.wordpress.com/