UAF grad student on hunt for ancient marine reptiles

August 16, 2016

Theresa Bakker

907-474-6941

Eric Metz has a passion for paleontology.

The University of Alaska Fairbanks graduate student in the College of Natural Science and Mathematics has been interested in dinosaurs since he was a kid. He happened to be on the expedition in July 2016 when a team led by scientists from the University of Alaska Museum of the North found the first dinosaur bones in Denali National Park and Preserve. He’s even teaching the Dino Camp on campus this summer.

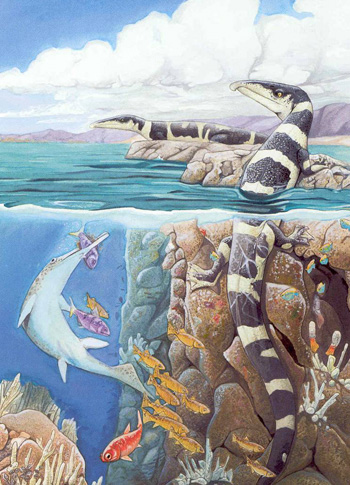

But his real interest are the animals that lived during the Age of Dinosaurs, not on land, but in Earth’s abundant oceans — ancient marine reptiles. These were some of the original sea monsters, creatures with terrifying Greek names. Ichthyosaur. Mosasaur. Plesiosaur.

Thalattosaurs are his specialty. “You can think of them as reptile seals,” he said. “They have this downturned snout, but we still don't know how they used it. Studying them allows us to have a better idea of the diversity of the planet and how groups of organisms go extinct.”

The name thalattosaur literally means “ocean lizard.” The long-tailed reptiles lived between 250 million to 201 million years ago. They had short back legs and a small pointed head. They averaged about 6 feet long and were similar to iguanas. One of the most complete thalattosaur specimens anywhere was found on a beach in Southeast Alaska in 2010. A team led by Pat Druckenmiller, the earth sciences curator at the UA Museum of the North, excavated it.

Metz wanted to conduct his master’s degree research with Druckenmiller because of his expertise with ancient marine reptiles and the museum’s growing collection. One of the skeletons he studies is a specimen from Oregon that has been called “the oldest bones in the state.” But he wanted even more.

On recent visit to the University of California Museum of Paleontology, Metz uncovered an interesting treasure — ancient marine reptile specimens, including ichthyosaurs and thalattosaurs, from the Hosselkus Limestone formation in the northern part of the state. The bones had been collected when paleontologists discovered a trove of skeletons in a remote area in the late 1800s. The initial expeditions were funded by Annie Alexander, a wealthy naturalist and philanthropist who joined the team and discovered many fossils herself.

Metz saw how well preserved the material was. “When I asked the curators of the museum if anyone had gone back, they said no one had tried. That made me determined to find the localities again.”

The fossils have been eroding out of the mountains for the last hundred years, with no one looking for them. “No one has gone back because, at the time they were discovered, the Shasta Mountain area was difficult to access. There were still grizzly bears in California!

“Since then, other Triassic locations have been found that were easier to access. However, the quality of the fossils, their high abundance and new access means now is a great time to go back.”

Metz and his collaborators didn’t have access to grant money or a wealthy benefactor. So they took a more modern approach to the problem, starting a campaign on a crowdfunding website called Experiment, which is dedicated to scientific research. The team was able to collect more than $5,000 in donations in about a month.

Turns out Metz has long been inspired to take the do-it-yourself approach when it comes to meeting his goals. As a young scientist, he read the book “Letters to a Young Scientist." He absorbed a lesson: If you want to pursue a career in this field, you should look first at where the funding and attention are directed, and then go in the other direction.

“In the field of paleontology, that meant ancient marine reptiles,” Metz said.

The expedition team plans to return to the California site in the summer of 2017. Metz hopes to find a number of ichthyosaur and thalattosaur specimens, even more complete than the ones already preserved in museum collection. He plans to complete some of the preparation work at the labs at UAF.

After Metz finishes his degrees, he plans to be a curator of a vertebrate paleontology collection. “In academia, it is a publish-or-perish mentality and, also, a who-you-know game. Being able to do collaborative work broadens my knowledge set and my contacts, and gives me the ability to publish."