A bad summer for birds on northern island

February 21, 2019

Ned Rozell

907-474-7468

“So, you get to write the obituary for Alaska,” George Divoky said.

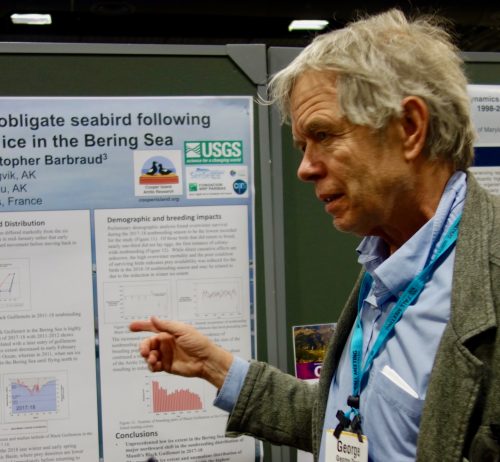

The seasoned biologist with the quick-twitch brain had spotted me, notebook in hand, standing near his poster at the December 2018 meeting of the American Geophysical Union in Washington, D.C.

Divoky’s greeting left me without words, but I knew what he meant. I had read enough posters in that session to see that walrus, clams, spectacled eiders and other creatures suffered greatly when an Idaho-size swath of sea ice went missing from the Bering Sea one year ago due to melting thin ice and stormy winds.

I shook Divoky’s hand, one that has wrapped around hundreds of hungry seabird chicks, and then put my pen to paper.

Every summer since 1975, Divoky has spent a few months living on Cooper Island, a crescent of gravel 25 miles southeast of Utqiagvik. He has gotten to know a few generations of Mandt’s black guillemots, sleek seabirds that hunt the edge of the sea ice.

The Cooper Island colony of breeding guillemots would probably not be there without Divoky’s help. In the early 1970s, he found 10 pairs of birds nesting beneath wooden boxes left there by U.S. Navy sailors after a 1950s expedition. Divoky propped up more boxes. He checked back, and the birds were using them. The colony of black guillemots expanded.

Over the years, Divoky upgraded the nest sites. Now, each June, the birds lay eggs in black plastic camera cases Divoky placed on the island to enable chicks to fledge without being eaten by polar bears.

After all this care, and all these years, Divoky and the birds had their worst summer together in 2018.

“It was very depressing,” he said. “The Arctic used to be white; now it’s all gray (the color of the open ocean). “Birds that I knew for a long time didn’t come back. It feels like a ghost town.”

From June through early September 2018, Divoky lived in a hut on Cooper Island and performed the same work he has done since the summer after Richard Nixon resigned.

First, he notes the birds’ return to the island for the breeding season from their winter wanderings on the northern ocean.

In 2002, he installed a metal roof on the small cabin that replaced the tents he used to live in. Since then, the birds would announce their arrival with the clatter of their feet as they landed on his roof. This year, he didn’t hear that racket for a long time.

“It felt really dead,” he said.

In time, some birds came back. Many did not.

“Adult survival is always around 90 percent (from the year before),” he said. “This year, it went down to 70 percent. Almost tripled the mortality.”

Of the 75 pairs of black guillemots that came back to Cooper Island in 2018, 25 pairs did not lay eggs. Of the 50 pairs that laid eggs, half did not sit on the eggs. Those eggs did not hatch.

“Those three things all point to a food issue,” Divoky said.

A few birds wear geolocator transmitters, which allow Divoky to see where his black guillemots spent the winter.

For the past four decades, they have wintered at the southern edge of the ice in the Bering Sea, often as far south as the Aleutian Islands. In 2018, the birds stayed well north of Bering Strait, some not far from Cooper Island.

“They’ve never wintered in the Arctic Basin before,” Divoky said. “They were 1,000 kilometers north of where they usually are in late April.”

About a year ago, in February 2018, warm winds came up and shoved thin sea ice out of the Bering Sea and melted a lot of it. This seems to have caused a northern migration of cold-loving fish that linger beneath the ice, which may be why birds that eat those fish, like black guillemots, remained so far north.

Though February 2018’s almost-ice-free Bering Sea had never been recorded in the era of satellites, February 2019 is on track to have the second-lowest ice extent that scientists have witnessed. It may be a new state of sea ice, due to warmer ocean temperatures in autumn that cause less ice to form. A mostly open Bering Sea in late winter is something creatures there have never seen.

“I don’t know how birds adapt to this sort of change,” Divoky said.

In June 2019, Divoky, who lives in Seattle, will return to Cooper Island for his 45th consecutive summer. At his poster last December, his finger slid downward on a graph showing yearly numbers of breeding pairs of birds.

“It really does look more like the end of the train wreck,” he said. “What happens next?”

Since the late 1970s, the University of Alaska Fairbanks' Geophysical Institute has provided this column free in cooperation with the UAF research community. Ned Rozell is a science writer for the Geophysical Institute.