A friend remembers Ted Stevens' advocacy for Alaska science

August 26, 2010

Ned Rozell

8/25/2010

474-7468

When Syun-Ichi Akasofu first approached Ted Stevens, the Japanese-American leader of the University of Alaska Fairbanks’ Geophysical Institute was desperate — he had responsibility for a rocket range that the Occupational Safety and Health Administration was ready to close, and he needed money for improvements.

Akasofu traveled to Washington, D.C., to meet the powerhouse Alaska senator. When Akasofu reached Stevens’ office, the senator informed him that he needed to head to Capitol Hill. “Can I come with you?” Akasofu asked. “I don’t see why not,” Stevens said. On the brief train ride, Akasofu pled his case for funds that would allow improvements to the rocket range his institute and the university had no money for. Stevens listened to him and deemed Akasofu’s cause important enough to turn around. “Let’s go back to the office right now,” Stevens said. The men caught a train going the other way.

Stevens assembled his staff and brainstormed until they found a way to fund a $20 million upgrade to Poker Flat Research Range. “My persuasion was no good,” Akasofu said. “He had a genuine fascination in science, and he was interested in the aurora. That’s why he helped, choosing it over what must have been hundreds of other requests.”

Akasofu, 80, recently sat down to remember his friend who did so much to help fund Alaska science.

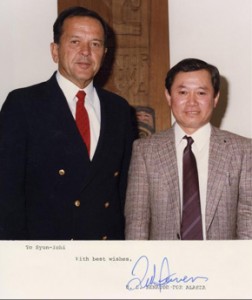

Ted Stevens died in the crash of a small aircraft north of Dillingham on August 9. He was 86. From that early meeting with Stevens, Akasofu developed a relationship with the senator, who regarded the former director of the Geophysical Institute and founder of the International Arctic Research Center as an advisor on scientific matters. They seemed a fitting pair — two men who were small of stature but had risen to lofty positions within their different fields.

In addition to the salvation of the university-owned rocket range, Akasofu credits Stevens with jumpstarting the Alaska Volcano Observatory after the 1989 eruption of Redoubt Volcano. After a jet flew through the ash cloud near Anchorage, and its pilot struggled to land the plane when all four engines seized, volcanologists in Anchorage and Fairbanks knew they could help prevent a repeat in the future. But ash from volcanoes was a hazard that federal agencies like the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Association, U.S. Geological Survey and Federal Aviation Administration didn’t consider their responsibility at the time. “I was told the only person who could ask three different departments to do something was the president,” Akasofu said. Not knowing the president, Akasofu asked the next best person. Stevens came through again with funding, and the Alaska Volcano Observatory was soon a reality. “Again, I think he had that genuine interest in science,” Akasofu said.

Akasofu also pointed out a concrete, glass and steel example of Stevens’ scientific curiosity and the clout that could make dreams into reality. As a founding scientist of UAF’s International Arctic Research Center, Akasofu had secured the Japanese government’s commitment to support a research institute where scientists explored the causes of a changing climate. The Japanese were willing to fund one half of the start-up costs of the center. In response to Akasofu’s request, Stevens wrote letters of support to Japan’s prime minister and also found money for the project via the National Science Foundation.

Eventually, those funds made it northward. The International Arctic Research Center, one of the most striking buildings on UAF’s campus, opened in 1999. “Without him, Poker (Flat Research Range) would be closed, and there would be no IARC or AVO,” Akasofu said. On the day he learned of Ted Stevens’ death, Akasofu drove to the International Arctic Research Center, where he works on several projects since retiring as director. He sat at his desk, but got nothing done. “I couldn’t work that day, I was so upset,” he said. “It was the same feeling as losing my father. “I don’t know how other people saw it, but I thought we were pretty close. He was a very warm-hearted person, really genuine. And it wasn’t just a gesture … I was kind of embarrassed by him a few times. Though I would always give him space when I saw him at functions, because everybody wanted to talk with him, he always saw me and then came over and bear-hugged me.”

This column is provided as a public service by the Geophysical Institute, University of Alaska Fairbanks, in cooperation with the UAF research community.Ned Rozell is a science writer at the institute.