‘After the Ice’ shares voices from the changing Bering Sea

September 28, 2020

Heather McFarland

9074746286

A new film series captures the stories of Indigenous communities immensely challenged

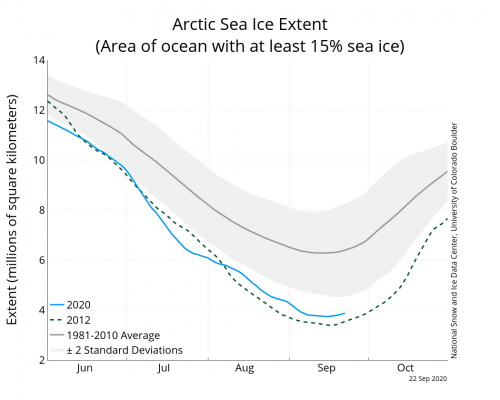

by sea ice loss in Alaska’s Bering Sea. The films will be released just weeks after the Arctic sea ice reached its annual

minimum, making 2020 the second lowest year on record.

“I fear, I fear not for myself but for the future generations,” said Elder Jerry Ivanoff,

a Unalakleet resident whose story was featured in the series. “The lack of ice, the

lack of snow, has an effect on the animals and the fish that we depend on to live.”

“After the Ice” is a three-part series funded by the Study of Environmental Arctic Change, a multi-disciplinary effort directed by Brendan Kelly of the University of Alaska Fairbanks International Arctic Research Center.

Beginning in early October the series will be broadcast by Alaska Public Media and available to stream for free at PBS.org. A virtual launch party will be held on Oct. 7 at 10 a.m. Alaska time (2 p.m. Eastern time), participate via Facebook Live or ZOOM. The premier screening will be followed by a panel discussion featuring video journalist Eli Kintisch, Bering Sea Elders Group executive director Mellisa Johnson and climate change educator Bill McKibben.

SEARCH sea ice scientists partnered with the Bering Sea Elders Group, an association of Alaska Native elders appointed by 39 Iñupiat and Yup’ik tribes in Alaska’s Yukon-Kuskokwim Delta and Bering Strait region, to create the films.

“These Indigenous communities have storytelling as a core component to their culture, so they are just really powerful partners in communicating what we’re observing as scientists and furthermore what they’re experiencing as communities, as families and individual hunters,” said Matthew Druckenmiller, a research scientist at the National Snow and Ice Data Center, UAF alumnus and science lead on the films.

The series paints an emotional picture of the effects of disappearing sea ice. People report seeing fewer birds and marine mammals. They describe pulling in nets stinking with dead salmon, likely spoiled by unusually warm water.

Imagine if asphalt in urban centers simply melted away, said Kintisch, who wrote and produced the films.

“That’s pretty much the reality for Native Alaskans and the millions of other people who live in the Arctic,” explained Kintisch.

Kintisch said he aimed to connect big global climate trends to individual stories, set to the backdrop of spectacular Arctic landscapes.

The series also documents hope.

Nick Hanson, a Unalakleet resident who competed in the TV series American Ninja Warrior, said young people are building homes at higher elevations, safe from winter storms that cause coastal flooding and erosion.

“Our ancestors, the Iñupiat people, they had to adapt and overcome every single day,” Hanson said in the film.

The coronavirus pandemic dashed plans of winter filming, so animations were used to illustrate some stories. Virtually every scene with winter sea ice was filmed by a local resident.

ADDITIONAL CONTACT: Eli Kintisch, elikint@gmail.com; Mellisa Johnson, 907-891-1229, beringsea.elders@gmail.com; Matthew Druckenmiller, 303-735-6472, druckenmiller@colorado.edu.

NOTES TO EDITORS: Please contact hrmcfarland@alaska.edu for additional photos.