Atmospheric rivers sometimes soak Alaska

August 29, 2019

Ned Rozell

907-474-7468

Nome, August 2019: More than 2 inches of rain falls in one day, setting a new record.

Thompson Pass, December 2017: 1.7 inches of snow piles up in 10 minutes. Seven feet of new powder blankets the pass in the next three days.

Ketchikan, December 2013: 23 inches of rain falls in five days.

These Alaska weather events were each the result of a great firehose in the sky that reaches from near the tropics to the far North. Meteorologists call it an atmospheric river.

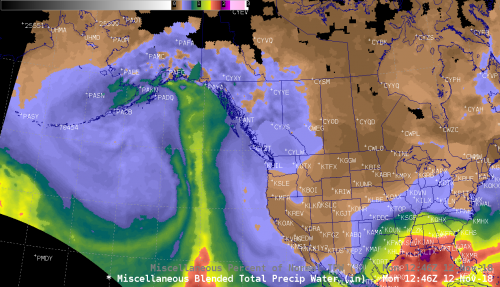

Scientists have long noted these flood-causing/wildfire-relieving “long, narrow plumes of enhanced atmospheric water vapor.” If you were to study weather maps of the entire Earth today, you would see about 11 atmospheric rivers.

Marty Ralph of the Scripps Institution of Oceanography in California, an expert on atmospheric rivers, described them as drought busters in his state. He also found atmospheric rivers were responsible for seven of eight flood events he studied on California’s Russian River.

When set up and propelled by other weather patterns, water vapor from near the equator flows in wide ribbons hundreds of miles long above our heads. If you sliced a theoretical cross-section from an atmospheric river, it would carry almost three times as much water, in vapor form, as what spills from the mouth of the Amazon River, Ralph said.

Some of that airborne water does not fall out as rain or snow. But when the super-wet air mass meets mountains or hills, a lot pours out.

The emptying of an atmospheric river on land can be good or bad if you occupy the ground beneath it. The atmospheric river that flooded Nome streets in early August shifted into Interior Alaska and the Alaska Range. Several inches of rain put the damper on many fires, including the Hess Creek Fire south of the Yukon River. After a lightning strike sparked it on June 21, that fire had consumed spruce and muskeg over a swath the size of New York City.

Alaska is in the crosshairs of several atmospheric rivers each season, including a type that would be welcome now, during the extended wildfire season on the Kenai Peninsula.

“The northeast Gulf Coast and Southcentral can get hammered by an atmospheric river when south flow originating near Hawaii creates the Pineapple Express that persists for days,” said Ed Plumb, warning coordination meteorologist for the National Weather Service’s Fairbanks office.

Aaron Jacobs, a hydrologist with the National Weather Service in Juneau, said researchers are studying whether atmospheric rivers are becoming more common in Alaska.

NASA scientists in 2018 said atmospheric rivers in our changing climate might become less frequent worldwide, but more intense. Duane Waliser of NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena predicted 10 percent fewer atmospheric rivers by the end of the 21st century, but said the remaining ones would be about 25 percent wider and longer. That means people would experience even more atmospheric-river conditions: Heavy rain and the wet winds that come with them.

Since the late 1970s, the University of Alaska Fairbanks' Geophysical Institute has provided this column free in cooperation with the UAF research community. Ned Rozell is a science writer for the Geophysical Institute.