Bowhead whales: A recent success story

January 28, 2021

Ned Rozell

907-474-7468

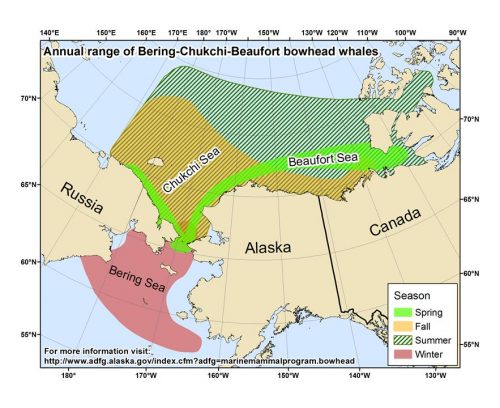

Bowhead whales are true northern creatures, swimming only in cold oceans off Alaska, Canada, Greenland, Svalbard and Russia. These bus-size whales have the largest mouths in the animal kingdom, can live for 200 years and can go without eating for more than a year due to their remarkable fat reserves.

Bowheads are also a rare wildlife rebound story, with the population north and west of Alaska now numbering more than 16,000. That’s up from the 1,000 or so animals Yankee whalers left behind in bloody waters at the turn of the last century.

Another part of the story is that bowhead whales also live in one of the fastest-changing regions on the planet. Biologists wonder about the future for the whales and the people who hunt them.

Craig George, a retired biologist with the North Slope Borough who lives in Utqiaġvik, has since the early 1980s studied the animal he describes as “an enormous, swimming head.”

From a perch made of sea ice, each spring George has counted bowheads rising for air between floes. As recently as a few days ago, he has listened to their unearthly calls beneath the ice using hydrophones lowered into the water.

As the past four decades have progressed, George has counted many more bowhead whales. At the same time, he and others living on Alaska’s northern coast have seen open water lapping at their shores in December — ice that forms on the ocean has appeared much later in the polar winter than just a decade ago.

Open ocean off Utqiaġvik in fall and early winter has resulted in what George has called a “climate changed,” with fall air temperatures more consistent with a town in Norway than the top of Alaska.

Through all that change, the whale with the reinforced hull of a head (used for breaking through ice) has thrived, in large part because people have left them alone, in a relatively untouched ocean.

“The assumption was that sea ice retreat would not be good for these animals, but they seem to be doing well — to date,” George said.

Bowhead whales have been food for many years to Native people of the northern coasts, including hunting crews from 11 villages in Alaska. Team members pursue whales from open boats, a risky endeavor that, when successful, provides food for much of the village.

Those Native hunters at Utqiaġvik had a hard time finding bowhead whales in fall 2019. Scientists looking for them during an airplane survey flown each year since 1979 did not see many bowheads, either.

“It was ecologically perplexing to us, and a real concern to whalers,” said Megan Ferguson, a biologist with the Alaska Fisheries Science Center, a branch of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. “We didn’t know if 2019 was the new normal, or a one-off.”

Ferguson, who lives in Seattle, also flew north for an autumn 2020 survey. Bowheads were everywhere her team looked, starting right after the survey plane lifted off from Utqiaġvik.

“We had sightings one right after the other,” she said.

The many bowheads Ferguson and her team spotted in 2020 meant that the long-lived whales were somewhere else in 2019, a year with record-breaking warm northern-ocean temperatures.

What was the difference between the years? Scientists noticed an abundance of whale food right off Utqiaġvik in 2020: shrimp-like, inch-long krill twitching by the thousands, as well as fatty copepods, which George calls “butterballs.”

What will 2021 bring for this iconic northern creature?

“It has been a good time to be a bowhead whale,” Ferguson said. “But things are changing, and it’s hard to predict what we’ll get in the future. Will whales consistently be available to the whalers in the years ahead?”

George, who has seen America’s northernmost town get warmer than he ever thought possible, said that bowheads have been having a good number of calves recently, usually an indicator that a species is doing well.

But he also said hunters and North Slope Borough wildlife veterinarian Raphaela Stimmelmayr noticed kidney-worm infections in bowheads, possibly spread to them from other types of whales venturing northward. And killer whales, one of the few natural predators of bowheads, have been documented in Arctic waters as sea ice shrinks toward the pole.

Even with all the uncertainty, “I would definitely say (bowheads are) a success story,” Ferguson said. George agrees that recovery of Alaska bowheads is one of America’s great conservation stories.

Ferguson and George pointed out that the recovery of this ocean giant was due to several factors. One was the end of commercial American whaling by men on wooden ships from New England. Another is the existence of pristine bowhead habitat far from the interests of people. A third is the actions of Native people who hunt the whales as part of their cultural identity.

“There’s few groups that fight as hard for conservation of this animal,” George said of organizations like the Alaska Eskimo Whaling Commission and the local government of Utqiaġvik, which helped fund the fall 2020 aerial survey of the whales.

Since the late 1970s, the University of Alaska Fairbanks' Geophysical Institute has provided this column free in cooperation with the UAF research community. Ned Rozell is a science writer for the Geophysical Institute.