Bringing the world to a standstill

May 20, 2021

Ned Rozell

907-474-7468

On a fine June day about 100 years ago, in a green mountain valley where the Aleutians stick to the rest of Alaska, the world fell apart.

Earthquakes swayed the alders and spruce. A mountain shook, groaned, and collapsed in on itself, its former summit swallowing rock and dust until it became a giant, steaming pit.

About six miles away, hot ash began spewing from the ground in a colossal geyser. During an eruption that lasted three days, one of the most vibrant landscapes in Alaska in 1912 became the gray badlands known as the Valley of 10,000 Smokes.

The great eruption that created the valley came from a smallish clump of rocks called Novarupta. Nowhere near as grand as the nearby Mount Katmai (the mountain that lost its top), Novarupta spewed an ash cloud 20 miles into the atmosphere, belching 100 times more ash than did Mount St. Helens. Though few people know its name, Novarupta was responsible for the largest eruption of the 20th century.

Rebecca Anne Welchman took a look at what might happen if Novarupta happened today. Welchman was a graduate student from Devon, England who became enchanted with volcanoes at the age of 13 when she traveled with her family to Hawaii. There, she saw the ocean quenching molten rock and the hook was set.

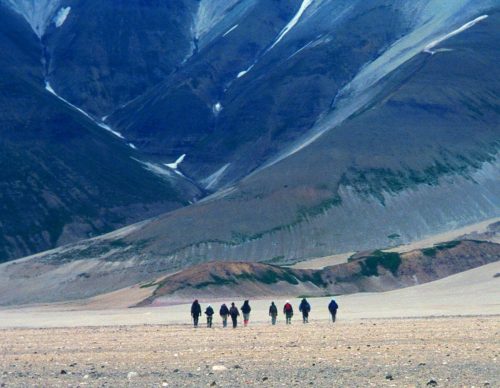

More recently, she hiked with volcanologist John Eichelberger on his annual summer filed trip to the Valley of 10,000 Smokes.

That trip inspired her to muse about the effects of a Novarupta eruption happening today, which is quite possible. She once presented a poster on the subject at the American Geophysical Union’s Fall Meeting in San Francisco.

“I think people in Europe and Asia don’t realize what Alaska could do,” she said in 2010, while standing in a cavernous poster hall amid hundreds of other scientists. “Another Novarupta would be bad news.”

Welchman was referring to a similar eruption’s effect on air travel. When Novarupta erupted, the sky was still the exclusive realm of birds and insects — Alaska was still a decade away from Ben Eielson’s first mail flight from Fairbanks to McGrath.

“Now, the North Pacific is one of the busiest air corridors in the world,” Welchman said. “More than 200 flights a day go overhead.”

To calculate the effects of a modern-day Novarupta eruption on today’s air travel, Welchman used a computer model called Puff developed by University of Alaska Fairbanks scientists and refined by Peter Webley of the Geophysical Institute.

She used the model to spew ash from Novarupta’s vent once a week for five years. She wanted to see which airports in the world would be affected.

“Most airports in the Northern Hemisphere would close,” she said. “Europe seems to get the brunt of it, but ash even reached Australia.”

Welchman summed up the return of Novarupta as follows:

“An eruption of Novarupta scale in today’s society has the potential to bring the world to a standstill by affecting the majority of airports in North America and Europe for several days at least. The worse-case scenario would cost in excess of $300 million just in terms of passengers and delayed flights.”

Since the late 1970s, the University of Alaska Fairbanks' Geophysical Institute has provided this column free in cooperation with the UAF research community. Ned Rozell is a science writer for the Geophysical Institute. A version of this column appeared in 2011.