Climate change and the people of the mesa

January 3, 2013

Ned Rozell

1/3/2013

Alaska was once the setting for an environmental shift so dramatic it forced people to evacuate the entire North Slope, according to Michael Kunz, an archaeologist with the Bureau of Land Management.

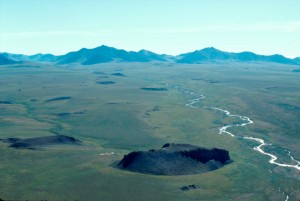

About 10,000 years ago, a group of hunting people lived on the North Slope, the swath of mostly treeless tundra that extends north from the Brooks Range to the sea. These people, known as Paleoindians, used a chunky ridge of rock west of the Colville River as a hunting lookout. Michael Kunz first discovered stone spear tips at the site, known as the Mesa, in 1978.

The people of the Mesa lived at a time when the Arctic was undergoing a change similar to what Alaska is undergoing today. As the world emerged from the last ice age, grasslands covered much of the Bering Land Bridge, a swath of land as wide as the distance from Barrow to Homer.

To survive in a place like the North Slope, where life is dicey in the best of times, humans needed a few things, Kunz said. One was technology, which the Mesa people had in the form of bone needles they used to sew weather-tight clothing. Another vital element was a large, plentiful source of food. Caribou were scarce during the time of the Mesa people, but bison roamed the grasslands in good numbers. Those bison are the key to how climate change affected these ancient Alaskans, Kunz said.

For many thousands of years, the area that is now Alaska was part of an enormous swath of dry grasslands that made up much of the Bering Land Bridge. About 15,000 years ago, the planet started evolving from the last ice age. Air temperatures became warmer, and things started to change. Glaciers began melting, sea level rose, and salt water slowly drowned the Bering Land Bridge. The encroachment of the ocean caused an increase in precipitation around the North Slope that allowed cottongrass and other sedges to nudge out the grasses preferred by bison.

About 12,000 years ago, as the North Slope evolved to what it looks like today, bison disappeared. The last evidence of the Mesa Paleoindians comes from around the same time. Kunz thinks the extinction of the bison from the North Slope, along with the simultaneous scarcity of caribou, caused the Mesa people to move or die out.

“This is totally the effect of the environment,” Kunz said. “Not only did it run the Paleoindians out of there, it made the place unlivable for anyone for 1,500 years.”

By examining bones and stone tools, archaeologists found that people moved back to the North Slope about the same time caribou returned after what seems like a population crash that lasted more than 3,000 years.

Kunz pointed out that car exhaust did not trigger the warming that may have chased the Mesa people from the North Slope. He said climate change has occurred many times before and is inevitable today. He suggests that the human species as a whole should think of how it will work around problems, such as rising sea level and the changes in agricultural zones caused by different weather patterns.

“The system has always been dynamic,” he said. “We’re not going to stop climate change. Just like the Mesa Paleoindians — if you can’t adapt or adjust, you’re going to disappear.”

Since the late 1970s, the University of Alaska Fairbanks' Geophysical Institute has provided this column free in cooperation with the UAF research community. Ned Rozell is a science writer for the Geophysical Institute. This column first appeared in 2001.