Climate shift may have spurred migration across Bering Land Bridge

June 19, 2018

Jeff Richardson

907-474-6284

A new study led by University of Alaska Fairbanks researchers found that the Bering Land Bridge's climate became wetter and warmer about 15,000 years ago, a change that likely encouraged the first human migration from Asia to North America.

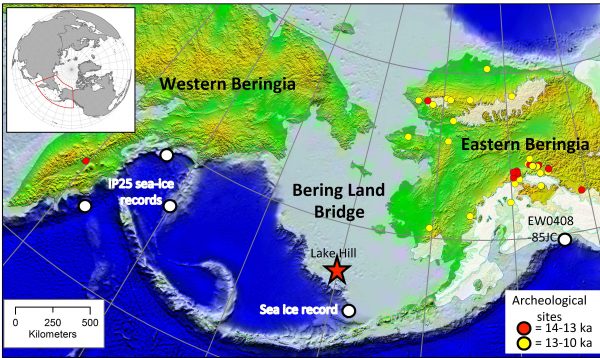

The Bering Land Bridge connected Asia and Alaska when sea levels were much lower during the last glaciation. The bridge provided an opening for the dispersal of people from Asia into the Americas.

Scientists were able to gauge climate conditions on the bridge by studying a 12-meter-long sediment core collected from a lake on St. Paul Island in the Bering Sea.

By analyzing organisms throughout the core, they constructed a climate record for the past 18,500 years. Almost all of the bridge and evidence of its past conditions is submerged below sea level today.

The study was published in the journal Royal Society Open Science today.

“We provide a temperature record pretty much from the center of the now-submerged land bridge,” said UAF professor of marine biology Matthew Wooller, director of the Alaska Stable Isotope Facility and lead author of the study. “This is a really unique record because of its location and length.”

The research team was able to show shifting climatic conditions in the past from the Bering Land Bridge by examining fossils from bugs, plants and spores in the sediment core. Many of those organisms live in specific conditions, so their presence offers evidence about past temperatures and moisture levels.

A marked climate shift to wetter, warmer conditions on the Bering Land Bridge coincides with the earliest appearance of humans in Alaska. Scientists have found archaeological evidence in Alaska that dates human habitation as far back as 14,200 years ago.

The climate shift likely meant a transition from steppe to forests in the Eastern Beringia. Meanwhile, horses declined in Interior Alaska as moose appeared, which could have affected human hunting practices and food availability.

The factors that contributed to human migration to North America have long been debated by scientists. The study provides more reasons to strongly consider environmental factors among those that "pushed" people eastward from Asia into the Americas, said UAF associate professor of anthropology Ben Potter.

“To me, this is a springboard for many new ideas,” said Potter, who contributed to the study. “While recent findings from genetics reveal a complex record of population history, studies like this are important to understand the ecological reasons for human migration.”

UAF researchers Emilie Saulnier-Talbot, Ruth Rawcliffe and Kyungcheol Choy, of the Water and Environmental Research Center and Alaska Stable Isotope Facility; and Nancy Bigelow, with the Alaska Quaternary Center, also contributed to the study. Other scientists on the project included Soumaya Belmecheri, University of Arizona; Les Cwynar, University of New Brunswick; Kimberley Davies, University of Southampton and Plymouth University; Russell Graham, Pennsylvania State University; Joshua Kurek, Mount Allison University; Peter Langdon, University of Southampton; Andrew Medeiros, York University; Yue Wang, University of Wisconsin-Madison; and John W. Williams, University of Wisconsin-Madison.

The Royal Society Open Science paper is available at http://bit.ly/2yt0b1h.

ADDITIONAL CONTACTS: Matthew Wooller, mjwooller@alaska.edu; Ben Potter, bapotter@alaska.edu