Engineer's stone tells of 'terrible rumbling and many memos'

July 7, 2017

The engineer's stone that sits just west of the Duckering Building will be rededicated

at 4 p.m. Friday, July 21, as part of the 2017 Nanook Rendezvous reunion.

The stone was created in 1967. In 2013, as construction of the new engineering facility

began, Professor Robert Perkins wrote a history of the monument and its humorous plaque.

By Robert A. Perkins

We begin our story with a little disambiguation. For several decades, the original “tradition stone” has moved about the campus and (according to some) the world. Its story starts in 1957, after UA President Ernest Patty banned alcohol on campus. In response, students dug a grave and buried “tradition” (and lots of empty beer bottles) beneath a 400-pound headstone. When Patty’s administration directed the destruction of the headstone, someone spirited it away. That former headstone, now called the “tradition stone,” has had a long and interesting history — but that is a separate story from the story of our engineering stone, which follows below.

The late 1960s brought a climate of protests; the engineering students tended to have fun with their civil disobedience. For example, a California architect designed a patio for the front of Duckering. The patio featured mounds of dirt that were ostensibly to be grassy areas for students to recline. Of course such a design, with its expectations of warm mosquito-free days, is generally useless in Fairbanks, and the students perceived the mounds as forcing them to take longer routes (on the sidewalks), rather than using the footpaths (now blocked by the mounds). So over the next year the engineers removed the mounds a little at a time until they had their shortcuts back.

Another time there was a call for volunteers to provide disaster aid following a volcanic eruption. Hundreds of students lined up to help, but there was no one to take their applications — the whole thing was a hoax.

Engineering and its stone

Against this backdrop, there were several serious rumors that UA engineers had a special stone of their own, apart from the tradition stone. Those rumors may have had their origin in blarney stones. Today engineers celebrate National Engineers’ Week during the last week in February; the celebration is often tied to George Washington, who was a surveyor and civil engineer when he wasn’t fathering a country and plaguing the British. However, for most of the 20th century, Engineers’ Week was celebrated to coincide with St. Patrick’s Day. St. Patrick is the patron saint of engineers and is reputed to have brought mortar to Ireland to help with church construction. At the University of Alaska, both the civil engineers and the mining engineers commemorated St. Patrick’s Day with a celebration, including an initiation that featured the kissing of the secret “blarney stone.” This stone (and successors) is lost to history; tradition has it that some of the early blarney stones were quite formidable, but all had been stolen by persons or forces unknown.

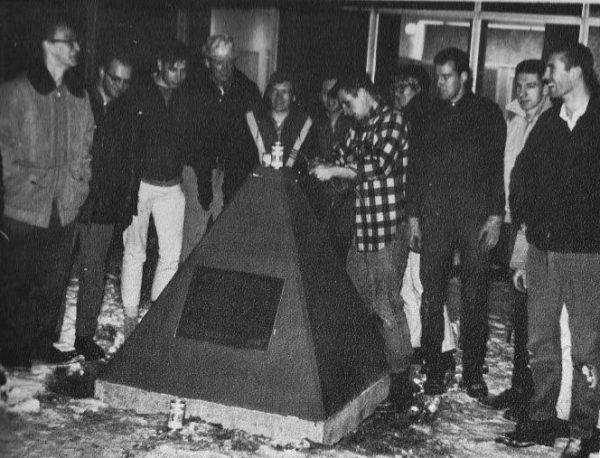

We do know that on Engineer’s Day, March 17, 1967, the Duckering Building was barricaded with snow, the hallways blocked with furniture and a holiday declared. For that occasion, the engineers wanted to make a statement by building a tradition stone of their own, one that, unlike the former headstone, would not walk or be transported away. Or for that matter, get lost or stolen like the blarney stones. So they developed a two-phase strategy to preserve the stone. One phase would be its bulk and structure; the second would be a formidable curse.

For civil engineers, the bulk should not have been a problem, except that to prevent vandals from gripping the stone with tongs, the stone was designed as a pyramid with sloping sides. This design would be easy if the creators were going to pour the concrete pointy end down, but in order to cast it with the pointy end up, a special form was necessary. The upward force from the liquid concrete would push up on the inside of the form, lifting it and allowing concrete to ooze from underneath. So a special framework of two-by-fours was built and bolted to the base. This would have been great engineering, except that the first time they tried it without the frame, the concrete oozed from beneath. Only then did they build the frame — proving at least that an engineer can learn from mistakes. The resulting pyramid was anchored to the base with dowels. The weight of base and pyramid is reputed to be 4,500 pounds (or at least 3,000 pounds, based on empirical evidence rather than historical precedent).

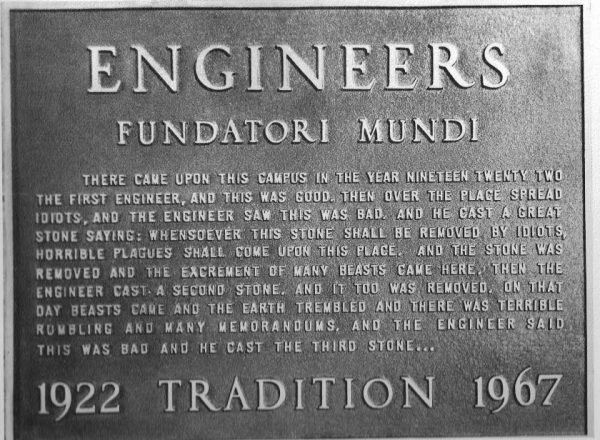

The curse is stated in a formidable bronze plaque fastened to the stone. It reads:

ENGINEERS

FUNDATORI MUNDI of the earth

THERE CAME UPON THIS CAMPUS IN 1922 THE FIRST ENGINEER, AND THIS WAS GOOD. THEN OVER THE PLACE SPREAD IDIOTS, AND THE ENGINEER SAW THIS WAS BAD. AND HE CAST A GREAT STONE SAYING, WHENSOEVER THIS STONE SHALL BE REMOVED BY IDIOTS, HORRIBLE PLAGUES SHALL COME UPON THIS PLACE. AND THE STONE WAS REMOVED AND EXCREMENT OF MANY BEASTS CAME HERE. THEN THE ENGINEER CAST A SECOND STONE. AND IT TOO WAS REMOVED. ON THAT DAY BEASTS CAME AND THE EARTH TREMBLED AND THERE WAS TERRIBLE RUMBLING AND MANY MEMORANDUMS, AND THE ENGINEER SAID THIS WAS BAD AND HE CAST THE THIRD STONE…

1922 TRADITION 1967

So who built the stone and placed the curse? Almost all the engineers belonged to the student chapter of the American Society of Civil Engineers. So the civil engineers built it. The contribution of the mining engineers is unclear — although we note mining engineers did better with explosives than concrete. Also, because there was no electrical or mechanical engineering, UA also offered a degree in “engineering science” that allowed study of other disciplines, and these students helped as well.

To nail down the St. Patrick connection, the pyramid was painted green. Before the days of RGB color, UAF engineers had fun with green. One winter, the engineers painted the snow with green fluorescent dye, although the low sun angle made the whole quadrangle look like “yellow snow.”

The date, 1922, mentioned twice on the plaque, is a story in itself. (And I’ll tell it — good thing I have tenure.) Judge Wickersham wrangled a land grant from the federal government and placed a cornerstone for the university in 1915. However, he had no authorization for a college or anything else, since the Alaska Territorial Legislature did not authorize the college until 1917. So there are good arguments for dating the beginning of the college to 1915 or 1917, except nothing happened, other than the cornerstone sans building. It was not until 1921 that Judge Bunnell was hired and began to organize a college. In fact the first student did not arrive on “campus” until 1922. So back to the dates on the plaque; 1967 would be the 50th anniversary of the college, if it was started in 1917, so the administration pumped up that date, changing all the college signs and stationary to remove the now heretical date, 1922. Thus the prominence of that date in bronze — where it could not be changed.

Despite the bulk and imprecations on the stone, there have been attempts to move it. In one operation, some creatures, somehow presumed to be students of Alaska Methodist University in Anchorage, succeeded in moving the stone to the parking lot. It was quickly replaced. However the stone may have been moved short distances since. Its current location over a manhole would not have been its original location.

Recent history

The stone now needs to be moved to make way for some utility construction associated with the new engineering building, planned for just south of current. How to move it without activating the curse requires some thought. Clearly we don’t want beasts or their excrement on Duckering or UAF. Perhaps we might gain some leverage by assuring that the stone is not moved by idiots, but rather as part of a carefully planned engineering effort. Further, we may get the souls who originally placed the curse to give us a waiver long enough to get the new building constructed.

The current situation is that, indeed, idiots still thrive and eight of them attempted to move the stone Wednesday night. Their plan was to lift it up into a pickup truck. None of them were engineering students, or math either, since dividing 4,500 pounds by eight would give each human lifter a load of over 500 pounds, and had they somehow heaved it up there, the pickup truck would have tilted and the front wheels lifted off the ground. They did try to remove the bronze plaque, but failed due to the vigilance our UAF campus patrol. Although the plaque is damaged, it is repairable and will be back, warding off idiots and beasts in the near future.

Robert A. Perkins, P.E., Ph.D., is a professor of civil and environmental engineering at UAF.