Finding fish in Alaska’s fossil record

May 24, 2018

Theresa Bakker

907-474-6941

Download text and photo captions here.

There are about 1.5 million named organisms on the planet. However, biologists estimate there are millions more yet to be named. And that doesn’t include the ones that have gone extinct.

All of the plants and animals on the planet are genetically related, and we can map the pattern of those relationships on a family tree. This “tree of life” helps us understand the history of major groups and how they changed through time.

Scientists have long grouped animals into similar categories by identifying their anatomical similarities, such as the colors of birds and the shape of fish jaws. Today we increasingly use evidence from molecular biology, especially in the form of DNA sequences, to estimate those relationships.

At a recent presentation at the University of Alaska Museum of the North, fishes curator Andrés López talked about northern pike. He touched on their geographic distribution across northern Alaska, North America and Europe. He described their long snouts and fierce jaws. He talked about their predatory nature and diet. And then he explained their relationship to other fish.

For more than 100 years, scientists relied on the science of observation to understand how fish were related. Using those methods, most scientists understood pike to be closely related to a group of fish known as mudminnows. These animals were thought to be distant relatives to salmon and other fish.

Then came DNA evidence. Suddenly there was a much more accurate way to measure and compare the similarities between species.

“We completed the first DNA sequence-based analysis of the mudminnow/pike relationship,” López said. “And through a series of follow up studies, we found strong evidence for a closer relationship to the salmon group than what anatomical evidence suggested. We also produced estimates of the timing of how the group diversified, when pike, mudminnows, salmon and whitefishes split from a series of common ancestors. “

In fact, the group including salmon and pike diverged from other fishes about 110 million years ago. And then 85 million years ago, the lineage including pike and mudminnows split from the salmon group. But López said he did not know what the fossil record showed about when pike relatives arrived in Alaska.

Then the museum’s earth sciences curator spoke up. “I’ve got esocoid fossils!” Patrick Druckenmiller said. “You should come look at them.”

‘Something really weird’

It was an exciting moment — a chance for the crowd to recognize that science is a collaborative effort, that new discoveries are made every day.

Druckenmiller said paleontology in particular benefits from working across scientific genres. “The field requires expertise from workers who study both living and extinct species to help make sense. I was excited to realize that our fossil fish are closely related to some of the fish that Andrés specializes in. I just needed to walk down the hall to talk to a world expert.”

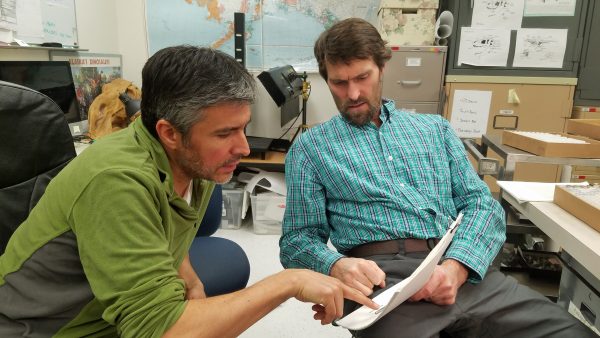

Druckenmiller and López met about a week after the pike presentation. In the fossil lab, they sat down in front of a tray of vials full of fish fossils. Most of the fish bones were very small, tiny jaws and teeth that required a microscope to see.

Druckenmiller made some images with a high-powered camera. He and a colleague had begun to examine the specimens to determine where they fit into the evolutionary record.

López was able to identify some of the samples as likely being ancient pike and mudminnows that were as much as 70 million years old. “Given that modern pike, mudminnows and salmon are broadly found in freshwaters at high latitudes in the Northern Hemisphere, it totally makes sense that their ancestors have been inhabiting these areas for a very long time,” he said.

In fact, fish fossils are commonly found at excavation sites, Druckenmiller said. “When it comes to fossils we run across, generally we have a rough idea of what they are. And then every so often we will run across something really weird and invariably it will turn out to be a fish.”

Understanding ancient ecosystems

For about 200 years, we have understood that dinosaurs once lived on Earth. In the 1980s, researchers verified that dinosaurs lived in Alaska. Today, scientists at the UA Museum of the North are describing an ancient polar ecosystem in what is now Alaska, with unique species found nowhere else in the world.

Druckenmiller and other scientists are working on a larger project to document all of the fossil vertebrates from the Prince Creek Formation in northern Alaska, which is mostly famous for its wide variety of dinosaurs.

“To understand the entire ecosystem that these polar dinosaurs inhabited, we also look at the other animals alive at the same time — including the fish,” Druckenmiller said. “In most of the deposits we are looking at, we find little fish fossils mixed in with the small bones and teeth of dinosaurs, so you really can’t find one without the other.”

López said natural history museums are perfect homes for biologists who specialize in classifying species. In a way, natural history museums grew on top of that research, so improving our understanding of how animals are related is one of their primary research products.

And after the two curators met to look at fish fossils, each scientist has a renewed appreciation for museum science. “It's great to have a group of people that is interested on the same questions to share ideas and find intersections between our respective work,” López said.