UAF researchers contribute to global glacier study

May 16, 2013

Diana Campbell

907-474-5229

5/16/13

Alaska’s melting glaciers remain one of the largest contributors to the world’s rising sea levels, say two University of Alaska Fairbanks geophysicists.

UAF Geophysical Institute researchers Anthony Arendt and Regine Hock joined 14 scientists from 10 countries who combined data from field measurements and satellites to get the most complete global picture to date of glacier mass losses and their contribution to rising sea levels.

“Sea level change is a pressing societal problem,” Arendt said. “These new estimates are helping us explain the causes of current sea-level rise.”

Their findings appear in the May 17 edition of Science magazine.

The study’s main finding is that from 2003-2009, the world’s mountain glaciers added just as much meltwater to rising sea levels as the Greenland and Antarctic ice sheets, said Alex Gardner, main author on the study and an assistant professor at Clark University in Massachusetts. The melt from the mountain glaciers alone explains one third of current sea level rise of about 2.5 millimeters, or a tenth of an inch, yearly, with glacial melt, ice sheet melt and the warming of ocean water equally sharing responsibility.

The study was compiled in order to provide new estimates to the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, a global report compiled every six years summarizing scientists’ best estimates of the environmental impacts of climate variations.

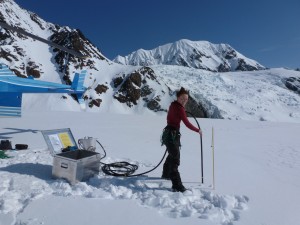

Part of Arendt’s and Hock’s contribution to the study was to assist in compiling a globally complete inventory of the Earth’s glaciers, with a focus on Alaska’s glaciers. Before the study, only about 40 percent of Alaska’s glaciers were inventoried. The two researchers also helped compile the most recent estimates of Alaska glacier changes, showing that Alaska remains one of the top contributors to global sea level.

“Alaska has a considerable amount of glacier ice, much of which is located near the coast, making it particularly susceptible to climate fluctuations,” said Arendt.

The two researchers emphasized the need for further study: Of all the regions examined, Alaska had some of the largest discrepancies between field and satellite estimates.

“More field data is needed to supplement satellite observations, so that we can better understand how glaciers in Alaska will respond to future climate variations,” said Hock.

ADDITIONAL CONTACTS: Anthony Arendt, GI, research assistant professor, 907-474-7427, arendta@gi.alaska.edu. Regine Hock, GI geophysics professor, 907-474-7691, regine.hock@gi.alaska.edu. Amy Hartley, GI public information officer, 907-474-5823, amy.hartley@gi.alaska.edu

ON THE WEB:

Science: ScienceMag.org

GI Glaciers Research Group: http://glaciers.gi.alaska.edu

NOTE TO EDITORS:Photos are available for download online at //news.uaf.edu/glacier2013 Science is the weekly journal of the American Association of the Advancement of Science and is considered the world’s leading journal of original scientific research, global news, and commentary.