Innoko is a long river short on people

April 11, 2019

Ned Rozell

907-474-7468

A quick comparison of two great rivers in America: One, the Wabash, runs 503 miles through Indiana, flowing past 4 million people on its journey to the Ohio River. The other, the Innoko, slugs its way 500 miles through low hills and muskeg bogs in west-central Alaska to reach the Yukon. About 80 people live on the Innoko, all of them in the village of Shageluk.

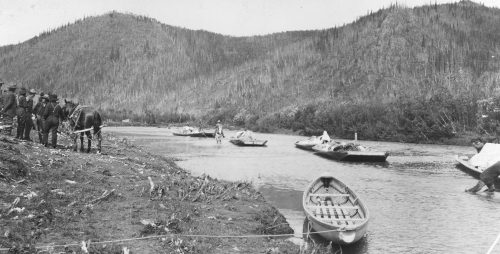

The fifth-longest river in Alaska, after the Yukon, Kuskokwim, Tanana and Porcupine, the Innoko is now at a historic low in human population. Its recent peak was around the Gold Rush days of the early 1900s, when miners established the town of Ophir on the extreme upper river, after a strike on nearby Ganes Creek.

About 120 people lived in Ophir in 1910. At the same time, 2,500 were sleeping in tents in the town of Iditarod on the river of the same name, the largest tributary of the Innoko. The Gold Rush also crowded the towns of Dishkaket and Dementi, both on the Innoko.

Those towns came and went, and no one lives in any of them today. More enduring was the Native village of Holikachuk, about 100 miles up from where the Innoko meets the Yukon.

The late anthropologist James VanStone of the Field Museum of Natural History in Chicago visited Holikachuk in 1972. From evidence including stone tools found on the flat near where a large slough enters the Innoko, he figured people had lived at Holikachuk since prehistoric times.

More than 120 people lived at Holikachuk in 1960, but they too are now gone. The village site flooded often during spring, when the Innoko swells over its low banks. In 1963, the residents voted to move 15 miles west, to the Yukon River village of Grayling.

The few dozen Holikachuk families chose the Yukon because it had great runs of king salmon, which do not swim up the Innoko, and freight barges visited Grayling many more times each summer than Holikachuk, if they made it there at all.

When the villagers moved away from Holikachuk, Shageluk became the only settlement on the entire squiggly spread of the lower Innoko, which features one of the most gradual drops of any Alaska waterway, losing just 1 foot of elevation every river mile.

As with Holikachuk, Shageluk has been occupied for perhaps as long as people have existed in Alaska. After contact with Russian explorers and American miners, the people in both villages endured both an epidemic of smallpox in 1838-1839 and the worldwide influenza epidemic of 1918 that wiped out entire villages on the Seward Peninsula.

Villagers in Shageluk also moved their town site, due to both spring flooding and a blowing snow problem in winter. In 1966, workers with the Bureau of Indian Affairs built a school on high ground about three miles downriver from Old Shageluk.

During his fieldwork on the river in 1972, James VanStone figured the Innoko had supported as many as 12 year-round Native settlements in the last few hundred years. One of the largest ancient village sites, in which about 100 people lived when Russian explorer Lavrenty Zagoskin visited in the mid-1800s, was right across the river from Shageluk.

In 2019, the Alaska river that drains an area larger than Vermont is home to fewer people than Vermont’s smallest town. The Innoko’s booms busted, and when geologists studied the oil and gas potential of the Innoko National Wildlife Refuge in the 1990s, they concluded it had none.

Despite its lack of people, the Innoko will soon be a noisy place. The boreal-forest lowlands are pocked with 26,000 lakes, the destination of more than 100 species of birds now winging their way north.

Since the late 1970s, the University of Alaska Fairbanks' Geophysical Institute has provided this column free in cooperation with the UAF research community. Ned Rozell is a science writer for the Geophysical Institute.