Project to investigate beluga whales' failure to rebound

September 13, 2017

Lauren Frisch

907-474-5350

A new collaborative research project will investigate potential factors that have caused the Cook Inlet beluga whale population to remain in severe decline since the 1990s.

Beluga whales were once common throughout inlet waters, historically numbering around 1,300. Unmanaged subsistence hunting in the mid-1990s led to a nearly 50 percent population decline. Today, despite conservation efforts, only about 340 Cook Inlet belugas remain.

A moratorium on the subsistence harvest of Cook Inlet belugas was established in 1999. The whales were listed as endangered under the Endangered Species Act in 2008, and critical habitat was designated in 2011. But Cook Inlet belugas have not recovered, and the reasons remain unknown.

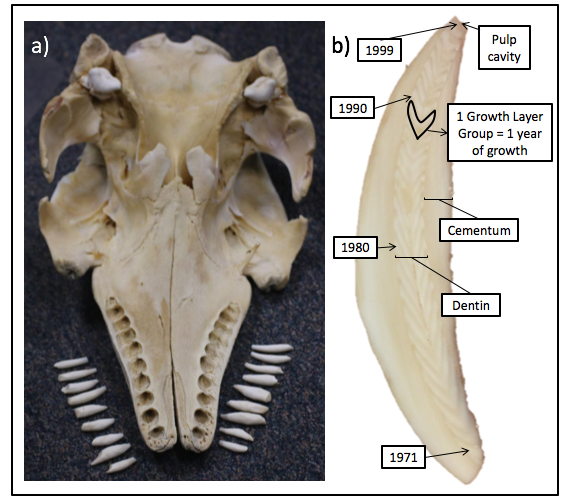

To better understand why the belugas have not rebounded, University of Alaska Fairbanks researchers Mat Wooller and Mark Nelson will measure stable strontium, carbon and nitrogen isotopes in beluga whale teeth to determine how feeding patterns may be changing over time. This information will help determine if changes in foraging ecology and habitat are affecting the ability of beluga whales to recover from the population decline.

“Like tree rings, teeth have annual growth layers,” said Wooller, a professor at UAF’s College of Fisheries and Ocean Sciences and Water and Environmental Research Center. “Measuring isotopes in these growth layers can reveal how whales’ feeding habits have changed over the life of an animal. By stacking records from many individuals sampled over time to create a long record of beluga behavior, we can create a long record of beluga behavior.”

Another component of the investigation will use existing data to build a population model to examine genetic factors that may be limiting population recovery. Because beluga whales use sound to find prey, a third group will use acoustic monitoring to detect where belugas forage for food. The three simultaneous projects will be coordinated by Mandy Keogh and Lori Quakenbush at the Alaska Department of Fish and Game.

The three-year research projects will start in fall 2017. Funding comes from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration's Endangered Species Act Section 6 Program, Georgia Aquarium and John G. Shedd Aquarium. The research is a collaboration between UAF, ADFG, the National Marine Fisheries Service’s Marine Mammal Laboratory, University of Washington, Florida Atlantic University and LGL Alaska Research Associates Inc. NOAA's Marine Mammal Health and Stranding Response Program has provided samples and data.

For more information on this project, refer to the ADFG press release.