North Korea blast lights up Alaska seismometers

September 7, 2017

Ned Rozell

907-474-7468

On Saturday night, Sept. 2, Matt Gardine was at home outside Fairbanks playing with his daughter when his phone beeped. As the seismologist on call with the Alaska Earthquake Center, Gardine’s duty was to get information out about detectable earthquakes right after they happen.

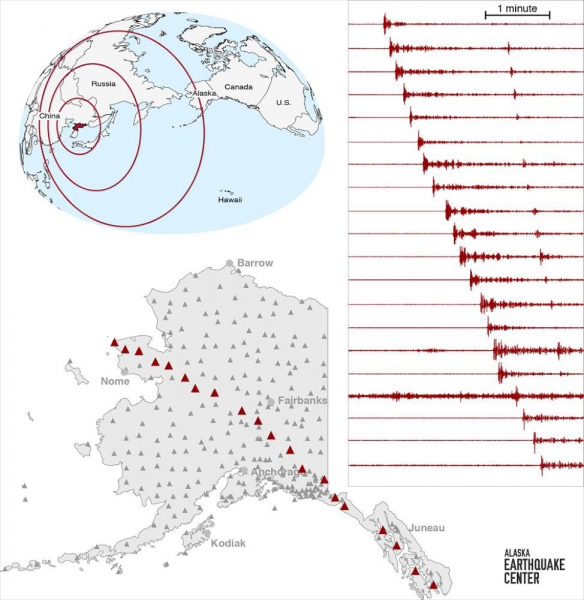

A few minutes earlier, at 7:30 p.m., a wave of energy had passed through Alaska. The shake had propagated through the entire planet, first reaching Alaska near the village of Wales and racing southeast from there.

Looking at the waveform that registered on seismometers from Tin City to Ketchikan, Gardine noticed its squiggle signature did not look like an earthquake. He saw its origin was North Korea, which doesn’t have many large earthquakes. He also thought it curious that the disturbance occurred right on the half hour, at 7:30.

Though people in China and Russia reported feeling a shake, which U.S. Geological Survey scientists estimated as magnitude 6.3 at its source in North Korea, Gardine suspected no Alaskans would detect the movement and that it was not an earthquake. He issued no alerts.

The shake that registered on Alaska seismometers and most sensitive instruments worldwide was an underground nuclear explosion by North Koreans. Since the Comprehensive Nuclear-Test-Ban Treaty in 1996, North Korea has been the only country conducting these tests.

“It was almost certainly underground,” Gardine said. “They did it to test that they can detonate a bomb, that their bombs are good.”

Detecting nuclear explosions is not the job of the researchers who work at the Alaska Earthquake Center, based at the university in Fairbanks. There is an Air Force agency, the Technical Applications Center, with that responsibility.

But Mike West, Alaska's state seismologist, said he and others at the center are “scientifically deeply interested” in the blasts. More than 400 seismometers planted around Alaska have registered two North Korea tests last year and one in 2015. Seismometers all over North America caught the same signals a few minutes later.

Underground explosions register with more clarity than earthquakes, West said. The recent burst was also followed by a second, smaller energy spike that was one of the reasons West invited all scientists to a post-Labor Day gathering to discuss the blast. The second signal was the energy of the nuclear bomb bouncing off the outer core of the Earth and returning to seismometers.

The North Korean bomb was a small blast compared to one in Alaska on Nov. 6, 1971. That’s when U.S. Atomic Energy Commission officials executed the largest underground nuclear test ever done in America. That 5-megaton bomb, named project Cannikin, was detonated in a shaft more than one mile deep beneath Amchitka Island in the western Aleutians.

Since the late 1970s, the University of Alaska Fairbanks' Geophysical Institute has provided this column free in cooperation with the UAF research community. Ned Rozell is a science writer for the Geophysical Institute.