Pioneer scientist determined aurora height over Alaska

November 30, 2017

Ned Rozell

907-474-7468

“Professor Fuller Drops Dead in Garden.”

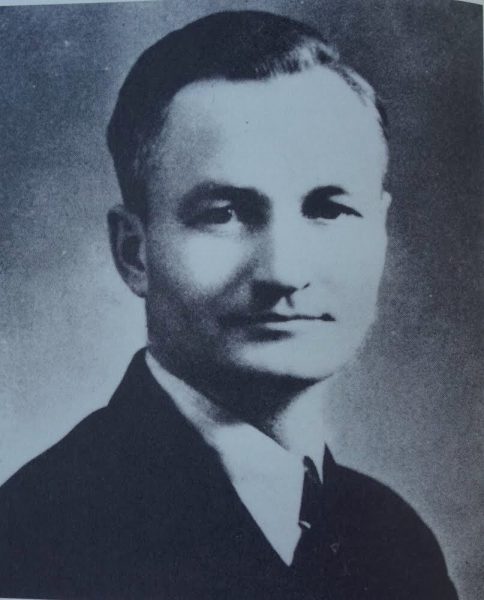

So reads the headline in the Farthest-North Collegian newspaper of June 1, 1935. In the story, an unnamed writer described how the wife of the only physics professor at the Alaska Agricultural College and School of Mines screamed when she found Veryl Fuller face down in his garden. He was 39.

Fuller left behind his Fairbanks-born wife Lillian and young twins Mary and Richard, as well as his unfinished study on the aurora borealis.

His was the first aurora experiment attempted in Alaska. Ninety years ago, scientists had hints the northern lights flared up when particles from the sun tickled gases in the thin air above their heads, but they didn’t know how high the aurora occurred above Alaska.

Fuller got the job of finding out. He was a dark-eyed, sensitive man who accepted a position at the Agricultural College and School of Mines in 1926. To get to Fairbanks from Ames, Iowa, where that same year he earned his master's degree in physics, Fuller boarded a steamship from Seattle and then a train from Seward to Fairbanks. Fairbanks had a gold camp feel, with no paved roads and as much activity in the surrounding hills as downtown.

Government officials and influential scientists were keen to know more about the aurora because America had just emerged from a period when the best way for people to communicate was through telegraph wires draped over the landscape. Communication by radio was one of those giant leaps that changes everything.

But there was an occasional problem with radio transmission and reception in the far North. At lower latitudes, radio waves bounce neatly from transmitter to receiver off the portion of the atmosphere from 60 to a few hundred miles above the ground. But at high latitudes, especially when the aurora is visible, that portion of the atmosphere steals energy from the signals. Sometimes radios of certain frequency ranges don’t work.

Up in the territory of Alaska, the young physicist Fuller did not know much about particles in the sky but was game to learn. Northward came $10,000 from the Rockefeller Foundation for a study conducted where the aurora is easy to see.

Fuller lived on the Fairbanks campus on a hill overlooking the flats of the Tanana Valley. He set up an experiment, copying as much as he could from an aurora-photography study done in Norway by scientist Carl Stormer. There, Stormer had found the aurora existed from about 60 miles above the ground and upward.

Fuller wanted to see if the elevation of the aurora was the same above Alaska. If it was, scientists would be able to infer that height was similar throughout the circumpolar North, and that the aurora indeed existed in the ionosphere, a mysterious region good for reflecting radio signals but hard to study.

Fuller was inventive and handy with tools, which was good because he had to make almost everything to get his project underway.

He created the first aurora-photographing station at his home on campus. He needed one more outpost to photograph the same auroras a good distance away at the same time. Using geometry, he could then determine the height of aurora displays.

For his second aurora observatory, Fuller drove his sedan on the two roads that led outside Fairbanks. After much searching, he found a log structure located 14 miles from his home. It was off the Fairbanks-to-Valdez Trail, about where North Pole High School stands today.

Fuller rebuilt the cabin so it could house a large black-and-white camera and the university’s car, which resembled a Model T Ford. Rolling the vehicle inside helped it remain warm enough to start on the Interior’s severe winter nights.

From August 1932 until his funding ran out in December 1934, Fuller sent his assistants on the adventurous drive to the cabin whenever there was aurora in the sky. Communicating with them on radios he had built himself, Fuller would try to photograph aurora displays in Fairbanks while his assistants did the same 14 miles away on the Tanana River floodplain. More often than not, their cameras failed, but through hundreds of attempts they captured a few dozen aurora images.

It was tiring work for Fuller and his student helpers, executed on long nights after days working on other projects. But by the time Fuller collapsed in his Fairbanks garden on May 30, 1935, he had acquired the data.

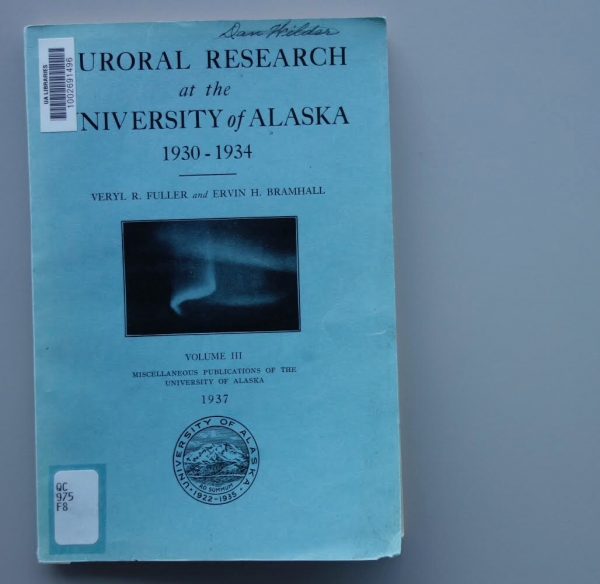

The task of finishing Fuller’s work went to a man named Ervin Bramhall. Bramhall labored over Fuller’s notes, photos and diagrams to follow through with the University of Alaska’s first scientific publication. “Auroral Research at the University of Alaska 1930-1934” was published 80 years ago.

In it, Bramhall wrote that Fuller had seen the aurora 73 percent of all nights during the winter of 1931 to 1932, and that the aurora over Alaska is at a similar height to the aurora over Norway. The lowest Fuller observed the aurora was 50 miles overhead. The highest aurora elevation was 360 miles up.

A Nebraska boy who married an Alaska girl, Fuller enjoyed life in the territory for less than a decade before he died. His small white gravestone endures a few miles from where he lived and did his aurora research, in the Clay Street Cemetery.

Since the late 1970s, the University of Alaska Fairbanks' Geophysical Institute has provided this column free in cooperation with the UAF research community. Ned Rozell is a science writer for the Geophysical Institute.