Play geoscience 'I spy' on the Richardson Highway

May 8, 2017

Meghan Murphy

907-474-7541

Are you tired of playing the same “I spy” game with your family as you drive to the Chitina River for fishing or to the Alaska Range for a weekend getaway?

Spice up the road trip with new points of interest from the geoscience students and teachers at the University of Alaska Fairbanks. As part of a class project, the students researched the geologic marvels flanking the Richardson Highway between Fairbanks and Gulkana Glacier. Then in April they took a road trip with their instructors — Chris Maio and Louise Farquharson — to present posters and a lesson at each feature.

“Many students had never been on the Richardson past Delta Junction and were so amazed that such an awesome landscape of mountains, glaciers and faults was just a few hours of easy driving from Fairbanks,” said Maio.

He said they can't wait to redo the trip with family members and friends. Here are eight highlights they're sure to share, along with geographical coordinates.

1. Ventifacts Junction

1. Ventifacts JunctionAbout 1.25 miles down Jack Warren Road, 64.07054, -145.70322

Anyone driving through Delta Junction will appreciate that “the windy city” lives up to its moniker. For thousands of years, wind-driven sediments have sandblasted stones in the area. This has eroded their surfaces into flat, angular planes that intersect at a “Y” ridge. The sculpted stones, called ventifacts, are easy to find on the north side of Jack Warren Road about midway between Phillips and Reeves roads.

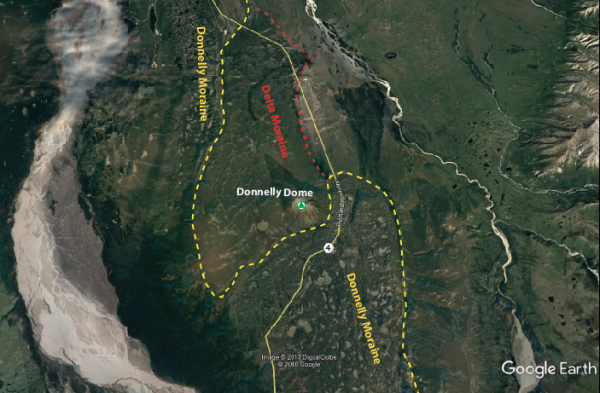

2. From one moraine to the next

2. From one moraine to the nextTurnout in front of Donnelly Dome, 63.77381, -145.76182

If you dig your foot into mud and push forward, a ridge of mud forms around the front and sides of your shoe. An advancing glacier forms a similar ridge, called a moraine, out of the dirt and rocks it pushes forward and deposits.

From Delta Junction south, the Richardson’s ribbon of asphalt overlays two major moraines

left by past glaciations. The Delta Moraine formed when a massive glacier advanced

north from the Alaska Range 40,000 and 70,000 years ago to where Delta Junction is

today. The next one, the Donnelly Moraine, formed 21,000 years ago and reaches north

from the range to near Donnelly Dome. Vegetation covers both moraines; however, the

younger moraine has more small hills because the area has had less time to erode. The

younger moraine also has small kettle lakes.

From Delta Junction south, the Richardson’s ribbon of asphalt overlays two major moraines

left by past glaciations. The Delta Moraine formed when a massive glacier advanced

north from the Alaska Range 40,000 and 70,000 years ago to where Delta Junction is

today. The next one, the Donnelly Moraine, formed 21,000 years ago and reaches north

from the range to near Donnelly Dome. Vegetation covers both moraines; however, the

younger moraine has more small hills because the area has had less time to erode. The

younger moraine also has small kettle lakes. 3. The Galloping Glacier

3. The Galloping GlacierThe old Black Rapids Lodge, on east side of highway, 63.52911, -145.85873

The original Black Rapids Lodge sits abandoned with views of the glacier across the street that once threatened it. In 1936-37, Black Rapids Glacier surged forward at a rate of about 250 feet a day. The lodge owners packed up and moved high, but the glacier, nicknamed the galloping glacier, eventually halted its advance and receded … for now.

4. River be dammed

Access across from Black Rapids overlook, 63.50283, -145.86127

You'll need to follow trail several feet. There is a trail sign and a turnout.

During the last 3,000 years, the Black Rapids Glacier surged forward and dammed the Delta River, diverting its flow into a mountain side. The flow carved a gorge beside the mountain that filled with the picture-perfect Rapids Lake after the glacier receded.

5. That’s a glacier?

Turnout near Castner Creek, 63.40245, -145.73461

Stop at the turnout to view from the car or take a short hike.

A lot of gravel and vegetation cover Castner Glacier, making it easy to miss. During this trip,

Castner Creek was still frozen and made a good, if sloshy, path to follow alongside

the glacier where you could hear little waterfalls trickle down the glacial ice into

melt pools. It was also a great place to play banjo. Never travel on a glacier unless

you are with an experienced guide. Crevasses and holes make glaciers dangerous.

Castner Creek was still frozen and made a good, if sloshy, path to follow alongside

the glacier where you could hear little waterfalls trickle down the glacial ice into

melt pools. It was also a great place to play banjo. Never travel on a glacier unless

you are with an experienced guide. Crevasses and holes make glaciers dangerous. 6. The mother of all Alaska faults

Turnout near the pipeline, 63.3863, -145.73147

You can see it from the road and a turnout with an interpretive sign.

It once created an earthquake felt in Seattle. It stretches westward to the base of

Denali — the tallest mountain in the nation. The Denali Fault is a type of tear in

the Earth’s crust that arcs more than 400 miles across Interior Alaska. From the turnout,

you can view the trans-Alaska oil pipeline where it has been engineered to cross the

fault without breaking during inevitable earthquakes.

7. A rocky rainbow

Turnout near Rainbow Ridge, 63.28533, -145.66075,

Site of rock glacier, 63.29129, -145.66018

Can be seen from the car or turnout.

Rainbow Ridge is a magnificent slope of colorful rock that soars high above the highway.

Two light-colored lobes stand out from the dark browns and reds. The lobes are rock

glaciers, whose cores are made of ice-cemented debris that slowly creeps forward.

Summer is the best time to see them, although they are there year-round.

8. Marking time with ashes

Off a dirt road from Richardson Highway, 63.20582, -145.51565

As you travel on the dirt road leading to Gulkana Glacier, you will notice mountains

to the left. On one you can see a light-colored splotch contrasting with dark browns.

The splotch is  ancient volcanic ash from an explosive eruption in the Wrangell Mountains 5 million

years ago. Scientists use the ash — called tephra —to help date events along the Denali

Fault captured in the rocks both above and below the ash.

ancient volcanic ash from an explosive eruption in the Wrangell Mountains 5 million

years ago. Scientists use the ash — called tephra —to help date events along the Denali

Fault captured in the rocks both above and below the ash.

See a Google map with waypoints, more pictures and descriptions at http://bit.ly/2pu6OtQ.

See a Google map with waypoints, more pictures and descriptions at http://bit.ly/2pu6OtQ.