New research reveals secret to Jupiter’s curious aurora activity

April 9, 2021

Rod Boyce

907-474-7185

The work by professor Peter Delamere and the rest of the team was published today in the journal Science Advances. The research paper was written by Binzheng Zhang of the Department of Earth Sciences at the University of Hong Kong; Delamere is the primary co-author.

Research done with a newly developed model of Jupiter's magnetosphere provides evidence in support of a previously controversial and criticized idea that Delamere and researcher Fran Bagenal of the University of Colorado at Boulder had put forward in a 2010 paper. The paper stated that Jupiter’s polar cap is threaded in part with closed magnetic field lines rather than entirely with open magnetic field lines, as is the case with most other planets in our solar system.

On Earth the aurora appears on closed field lines around an area referred to as the auroral oval. It’s the high latitude ring near — but not at — each end of Earth’s magnetic axis. The problem, Delamere said, is that researchers were so Earth-centric in their thinking about Jupiter because of what they had learned about Earth’s own magnetic fields.

“We as a community tend to polarize — either open or closed — and couldn’t imagine a solution where it was a little of both,” said Delamere, who has been studying Jupiter since 2000. “Yet in hindsight, that is exactly what the aurora was revealing to us.”

Open lines are those that emanate from a planet but trail off into space away from the sun instead of reconnecting with a corresponding location in the opposite hemisphere.

Within that ring on Earth, however, and as with some other planets in our solar system, is an empty spot referred to as the polar cap. It’s a place where magnetic field lines stream out unconnected — and where the aurorae rarely appear because of it. Think of it like an incomplete electrical circuit in your home: No complete circuit, no lights.

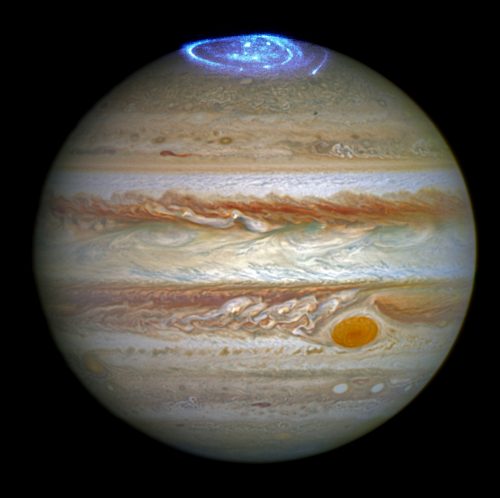

Jupiter, however, has a polar cap in which the aurora dazzles. That puzzled scientists.

The arrival at Jupiter of NASA’s Juno spacecraft in July 2016 provided images of the polar cap and aurora. But those images, along with some captured by the Hubble Space Telescope, couldn’t resolve the disagreement among scientists about open lines versus closed lines.

So Delamere and the rest of the research team used computer modeling for help. Their research revealed a largely closed polar region with a small crescent-shaped area of open flux, accounting for only about 9 percent of the polar cap region. The rest was active with aurora, signifying closed magnetic field lines.

Jupiter, it turns out, possesses a mix of open and closed lines in its polar caps.

“To me, this is a major paradigm shift for the way that we understand magnetospheres.”

What else does this reveal? More work for researchers.

“It raises many questions about how the solar wind interacts with Jupiter’s magnetosphere and influences the dynamics,” Delamere said.

ADDITIONAL CONTACT: Peter Delamere, University of Alaska Fairbanks Geophysical Institute, padelamere@alaska.edu

The paper is available at https://advances.sciencemag.org/content/7/15/eabd1204. A full-length story version about the research, with an additional graphic, is available on the Geophysical Institute website at www.gi.alaska.edu .