Rural residents will aid Coast Guard using unmanned aircraft

June 29, 2021

Rod Boyce

907-474-7185

The project, supported by the University of Alaska Fairbanks, will also provide data to enhance local decision-making on environmental and community issues.

Seven residents of Unalakleet, about 150 miles southeast across Norton Sound from Nome, are participating in the program. It's run by Jessica Garron, an affiliated researcher with the Alaska Center for Unmanned Aircraft Systems Integration at the UAF Geophysical Institute. Garron is a research assistant professor in UAF's International Arctic Research Center.

“There is a disconnect between what the Coast Guard can do in Alaska in a spill response type of environment,” Garron said. “One of those problems is a 24- to 48-hour lag time in getting response teams into rural Alaska."

To reduce that lag, the project includes a goal of training a local workforce that can help during emergency response events. The effort could also support bulk fuel storage inspections and help enhance local, science-based decision-making.

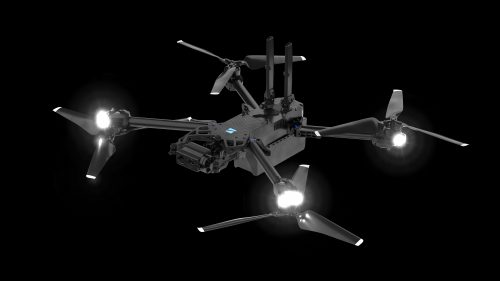

The unmanned aircraft systems, or UAS, project runs through April 2022 and is funded by the U.S. Department of Homeland Security.

The UAS project was born from a program initiated by the Native Village of Unalakleet. In 2018, the group received funding from the Bureau of Indian Affairs’ Tribal Resilience and Ocean and Coastal Management and Planning Program to assess the use of unmanned aircraft systems and online tools to improve local decision-making.

That program was led by John Henry Jr., deputy director of the Native Village of Unalakleet; Margaret Hall, associate director of the national nonprofit Model Forest Policy Program; and Garron. Hall and Henry, who is joining six other Unalakleet residents in the training, are co-investigators in the project.

Henry said the BIA grant funding had two elements.

“One was to address future climate-related ocean and coastal management planning challenges that tribes may incur, and the second is to build long-term resilience through the establishment of a self-sustaining, localized and ongoing data collection and analysis program,” he said.

To do so, the project team chose nine scientific study areas to assess based on Henry’s local insight: coastal erosion, river and sea flood preparation, infrastructure, water quality, air quality, cultural and historical site identification, extractable resources, wildlife, and plant community.

Unmanned aircraft were seen as useful for supporting local decision-making in several of those areas.

“The unmanned aircraft systems might be able to offer the ability to build on the traditional ecological knowledge that is passed on by elders and other members of the community,” Hall said.

“This project is also hopefully an economic development opportunity for some of the members of the Norton Sound area, especially Unalakleet,” she said. Other nearby villages, such as Elim, Shaktoolik and Golovin, could pursue their own programs or participate in this one, if it's expanded, she said.

The program could help with detection and response to oil spills, Hall said. The Norton Bay Intertribal Watershed Council has expressed concerns about oil spills and response times as declining sea ice allows more marine traffic. Spills in the Bering Strait are also of increasing concern to the Coast Guard and other government entities.

Participants in the UAS project were selected in March. Virtual training required by the Federal Aviation Administration wrapped up in early June. The participants will take the FAA Part 107 certification exam in Anchorage. One participant has already been certified.

The program’s leaders hope the Unalakleet project can be replicated elsewhere in Alaska and in Coast Guard sectors in the Lower 48.

ADDITIONAL CONTACT: Jessica Garron, University of Alaska Fairbanks, jigarron@alaska.edu