Scientific evidence found of overwintering ‘zombie fires’

May 19, 2021

Heather McFarland

907-474-6286

New research provides the first scientific evidence of overwintering fires in Alaska and Canada boreal forests. Due to climate change, these “zombie fires” appear to be increasing in frequency.

The study published today in Nature was led by Vrije University Amsterdam with co-authors at the University of Alaska Fairbanks and U.S. Bureau of Land Management’s Alaska Fire Service. The researchers found that extreme summer temperatures and intense burning enable some wildfires to smolder in peat beneath snow during winter, even when temperatures drop to minus 40 degrees Fahrenheit. When warm and dry conditions arrive in spring, these fires flare up.

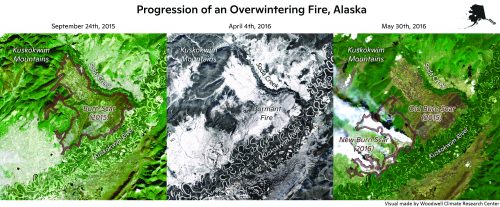

The study combined information from fire managers with satellite imagery to identify overwintering fires. Though these fires are invisible to satellites while smoldering under the snow, the location and timing of their re-emergence gives them away.

By analyzing how far these fires spread underground and how fast they re-emerge after spring snowmelt, the researchers developed an algorithm to reliably distinguish between overwintering fires and new ignitions by lightning or human activities.

Overwintering predominantly happens in peaty soils that experienced deep burning.

“We also saw a clear relationship between warm summers that create large and intense wildfires and the number of fires that manage to overwinter,” said lead author Rebecca Scholten, a Ph.D. student at Vrije University Amsterdam.

Although new to the scientific community, overwintering fires are not entirely new to fire managers.

“I've worked in fire in Alaska for 30 years, and at one time I would have said the overwinter holdover was a very rare phenomenon,” said co-author Randi Jandt, a fire ecologist at the Alaska Fire Science Consortium housed with the UAF International Arctic Research Center. “After the large fire seasons in 2004, 2005, 2009 and 2015, however, we noticed a surprising number of these overwintering fires.”

Since 2005, over 40 overwintering fires were reported in Alaska, according to information summarized in Alaska’s Changing Wildfire Environment. The $49 million Swan Lake Fire on the Kenai Peninsula and the Shovel Creek Fire northwest of Fairbanks were both 2019 fires that burned deeply, smoldered all winter and reignited in 2020.

The study’s findings have direct implications for Alaska fire managers. Fire management budgets and personnel are already strained by intensifying wildfire regimes and population expansion into formerly wild land.

“Overwintering fires flare up at a time when fire management units are not yet fully staffed and aircraft may not yet be on contract,” explained Jandt. “The study findings about when and where these fires occur can help fire management agencies operationally to better anticipate and prioritize detection efforts in the spring.”

With climate change, temperatures in the Arctic are expected to increase much faster than in other parts of the world. Alaska is already experiencing the impacts, and the study’s authors suggest that overwintering fires may become more common. The state’s snowpack melts nearly two weeks earlier in the spring compared to the late 1990s, and over 2.5 times more acres burned from 2001–2020 than during the previous two decades.

Overwintering fires are still relatively rare, causing around 1% of the total area burned in the Alaska and Canada study regions on average. Yet in exceptional years they can contribute considerably to the area burned and regional smoke emissions.

ADDITIONAL CONTACTS: Randi Jandt, rjandt@alaska.edu, 907-474-5088; Rebecca Scholten, r.c.scholten@vu.nl.

NOTE TO THE EDITORS: Please contact Heather McFarland, hrmcfarland@alaska.edu for additional photos.