Sifting volcano paydirt to help forecast eruptions

October 3, 2019

Ned Rozell

907-474-7468

More than 100 volcanoes pimple the adolescent skin of Alaska, spreading from ear to ear. Some are loud, flamboyant and obnoxious. Others are sneaky and quiet, escaping notice until a pilot sees a gray plume that wasn’t there yesterday.

Because people live on the slopes of these volcanoes and thousands more fly through their blast zones each day, scientists want to forecast eruptions with more precision.

For the past 30 years, scientists at the Alaska Volcano Observatory have had their fingers on the pulse of volcanoes, looking for signs of shakiness and sending out alerts when something is going on. On an early October 2019 day, for example, AVO’s webpage showed that Cleveland, Semisopochnoi and Shishaldin volcanoes were all a bit restless.

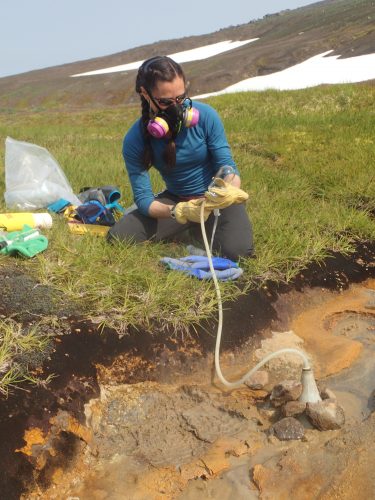

When an eruption happens, scientists with the observatory use all their information streams to get warnings out. Their tools include seismometers planted into volcano flanks, satellites that send back infrared pixels of hotspots, GPS units that show volcanoes inflating like balloons, gas sensors that tell what is wafting from a crater, microphones on volcanoes that hear explosions, and rocks and ash collected from mountainsides.

That’s a firehose of information, and scientists are happy to have it all. There is so much, though, that researchers rarely get to all of it before another eruption happens.

A team of them will set up four Ph.D. students to dig into that data paydirt, to see if they can find a key to better eruption forecasts.

Taryn Lopez is one of the scientists who is looking for those graduate students.

“We’re pretty good at saying an eruption is going to happen,” she said of the current state of Alaska volcano monitoring. “We’re not so good at predicting how big it will be or how long it will last.”

Lopez, an expert on volcanic gases at the University of Alaska Fairbanks Geophysical Institute, thinks students combing all this information on eight specific Alaska volcanoes might come up with something other busy people have missed.

“If we put our tools together, we can say a lot more,” she said.

She and her teammates on the project, including her husband David Fee, the coordinating scientist of the Alaska Volcano Observatory, have chosen eight Alaska volcanoes for a closer look. Four of them — Okmok, Bogoslof, Augustine and Redoubt — are the somewhat predictable big-mouth variety that tend to spew ash way up where jets are flying great-circle routes.

The other four are sneaky ones — Cleveland, Shishaldin, Pavlof and Veniaminof — all of which have also disrupted air traffic in the past with little warning.

“If we could make any progress on forecasting these eruptions, that would be a big breakthrough,” she said.

To get there, Lopez and team members Ronni Grapenthin, Jessica Larsen and Pavel Izbekov are looking for Ph.D. students who will spend four years mining for clues given by the eight volcanoes. As the National Science Foundation-funded study matures, they will hire two postdoctoral researchers to condense the others’ results into eruption-forecasting models.

Later, on deadline, Alaska Volcano Observatory scientists might plug information into those models and get better answers on how big an eruption will be and how long jets might be grounded from flying over Alaska airspace.

Since the late 1970s, the University of Alaska Fairbanks' Geophysical Institute has provided this column free in cooperation with the UAF research community. Ned Rozell is a science writer for the Geophysical Institute.