Study reveals how Arctic Ocean drives ice melt

March 2, 2016

Yuri Bult-Ito

907-474-2462

Unprecedented ice melt in the Arctic Ocean is not caused by warming air alone, according

to a recent study that emerged from a workshop at the University of Alaska Fairbanks.

Sea ice in the Arctic has continued to get thinner and smaller and to move faster

during the past two decades.

Examining a collection of observational data obtained for more than two decades, a

group of more than two dozen international researchers gathered at the March 2013

workshop to tackle the question of whether the increasing warmth of the Arctic Ocean

itself is melting its own cover of ice.

The results were published in December in the Bulletin of the American Meteorological

Society.

Researchers investigated how the effects of ocean currents, salinity, wind and ice

interact with one another to accelerate sea ice melting. They showed that small changes

in ways the ocean transports heat to the ice cover could have a substantial impact

on future changes in Arctic ice cover.

“Sea ice loss has implications for governance, economics, security and global weather,

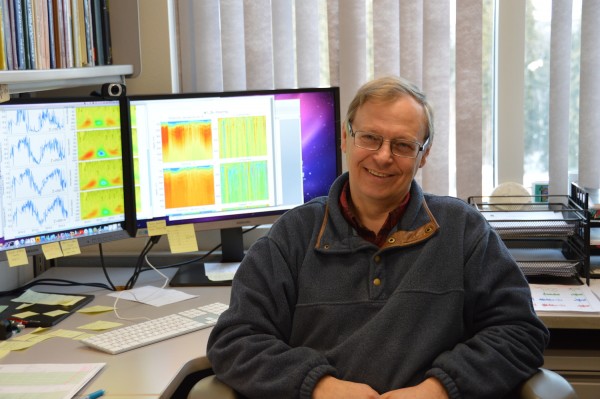

so it is critical to understand how ocean, ice and air interact,” said Igor Polyakov

of the UAF International Arctic Research Center, who was one of the lead authors of

the study.

The Atlantic and Pacific Oceans are heating up and warmer currents are flowing into

the Arctic Ocean. The heat from these currents would melt the Arctic sea ice instantly,

Polyakov said, but so far it hasn’t happened because the warm currents don’t come

into direct contact with the ice.

“The reason is these currents are saltier, therefore heavier, so they sink deeper

into the ocean. Colder, fresher surface water partly shields the ice on the surface

from warm water below,” he said.

Wind and faster-moving ice floes stir the ocean below, causing cold surface water

and warm waters below to mix. As they are mixed, warmer water is brought to the surface

and melts the ice cover from beneath it.

As this process continues, more sea ice melts.

The heat from the sun not only directly melts the sea ice but also heats up the water

between ice floes, which is darker than ice and absorbs more heat. The heat from the

sun also penetrates the thin areas of the ice, causing them to break from bigger,

solid masses of ice. These smaller ice floes move freely.

Fresh water rushing from the large Siberian and North American rivers add more warm

water to the ocean and accelerate ice melt, according to the paper.

The Arctic is warming faster than any other region on the planet.

“Sea ice melt in the Arctic is one of the most visible indicators of global climate

change,” said Peter Winsor of the UAF Institute of Marine Science, who contributed

to the study.

The study presents the most comprehensive summary so far of the current understanding

of how heat reaches the ice base from the original sources, such as currents from

different oceans and river discharge. The study gives key directions for creating more

realistic future projections of the warmer and more dynamic “new Arctic.”

“Physical mechanisms within the Arctic Ocean impact biological, chemical, geological

and physical processes and occur across sovereign state boundaries,” noted Polyakov. “So

it is really important that we make multidisciplinary, multiagency and multinational

efforts to reduce uncertainties in the projections of the future Arctic.”

The Chapman Chair Untersteiner Workshop was hosted by the UAF College of Natural Science and Mathematics and the International Arctic Research Center at UAF.

ADDITIONAL CONTACT: Igor Polyakov, UAF International Arctic Research Center, 907-474-2686, igor@iarc.uaf.edu.

ON THE WEB: The paper, entitled “Toward quantifying the increasing role of oceanic heat in sea ice loss in the New

Arctic,” was published in the Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society. Learn more

about An Untersteiner Workshop: On the Role and Consequences of Ocean Heat Flux in Sea Ice

Melt.