UAF takes look at parvo cases in Interior

April 18, 2016

Meghan Murphy

907-474-7541

All it took was a slight mutation in a cat virus. Then puppies began dying all over the world from canine parvovirus.

“I was 6 or 7 in Germany, and I remember my dad wanted to get a boxer puppy, but he couldn’t because there were no puppies,” said Dr. Karsten Hueffer, a veterinarian and associate professor of veterinary microbiology at the University of Alaska Fairbanks.

Hueffer studied the evolution of the canine parvovirus type 2, also known as parvo, at Cornell University from 1999 to 2003. He said the virus spreads through ingestion and defecation. It wreaks havoc on a dog’s gastrointestinal tract, causing severe diarrhea and dehydration. Although adult dogs can die from parvo, puppies are the most susceptible.

“In the mid-'70s, the parvovirus mutated to infect dogs as well as cats,” he said. “It swept around the world in three years because it’s so hardy. You step in dog feces in Greece and then get on a plane. You land in New York and walk on the street where a little piece of dog feces falls from your shoe. We all know what dogs do when they smell dog feces, right? They might even go there and eat it.”

Scientists quickly developed a vaccine against the virus, which relegated the once pandemic disease to a manageable state. Yet dog owners and mushers in Interior Alaska this winter began to worry as news of parvo deaths grew in the area.

At least 20 dogs in the Interior died this winter as a result of parvo, according to Dr. Arleigh Reynolds, a veterinarian and associate dean of the UAF Department of Veterinary Medicine. The well-known champion musher stressed that the number of deaths is small compared to the thousands of dogs living in the area. He cautioned against describing the deaths as an outbreak.

“We can’t define whether we’re seeing more than usual parvo cases because we don’t have the baseline data,” he said. “People don’t have to report the virus to state or federal officials.”

Of the 20 confirmed parvo deaths, most were sled dogs, although some were pets, Reynolds said. As expected, many were puppies, but there were also some adult dogs.

Why the deaths?

Reynolds and his faculty, including Hueffer, are working with Cornell University to learn more about why the dogs died. Cornell is known for its diagnostic facilities and extensive research on canine parvovirus. Researchers there are analyzing blood samples collected from some of the 20 dogs that died from parvo in Interior Alaska.

While not all the results are in, Reynolds said enough lab work was done to show that it is highly unlikely that Interior Alaska is experiencing a new strain of canine parvovirus that is resistant to vaccinations.

He also said researchers analyzing the blood samples did not see antibodies specific to the parvovirus — the telltale sign that the deceased dogs had developed immunity. Antibodies either destroy the virus or flag it for destruction. The dogs develop these antibodies by surviving parvo or by getting a series of specifically timed parvo shots and boosters.

Reynolds said the lack of antibodies in the samples could mean either the dogs did not receive the parvo vaccine or the vaccine wasn’t administered or handled correctly.

“There are so many places along the way where you can run into a problem that would take a perfectly good vaccine and render it ineffective,” Reynolds said. “The whole chain along the way has to be intact in order for the vaccine to work.”

If a vaccine freezes and thaws or loses refrigeration during shipping, the vaccine can lose potency. A dog that is ill or stressed might not respond to the vaccine. It’s essential that a dog gets its vaccine shots in the right order with the right timing.

Reynolds and Hueffer both emphasized that people who regularly bring their dogs to veterinarians should not worry. They said the risk comes when people give the canine parvo vaccine themselves. The vaccine is available in stores and online.

Dr. Greg Pietsch, a veterinarian at the Aurora Animal Clinic, described the typical protocol that veterinarians use when giving the vaccines.

“Most vets use a series of vaccines for puppies,” he said. “Our typical schedule is eight, 12 and 16 weeks. Sometimes people will start a little younger than that, sometimes people will go a little bit longer than that. Usually puppies end up with three to four vaccines about three to four weeks apart, and it’s important that they get vaccines out until at least 16 weeks. Then come the booster shots.”

Dogs receive a booster shot at one year and then need another booster thereafter every one to three years, depending on the quality of the vaccine. Pietsch said not all parvovirus vaccines for dogs are created equal. Some stimulate immunity better than others.

He said it’s important to realize that the parvo vaccine for dogs is usually part of a combination vaccine that immunizes dogs against several viruses and diseases like distemper and hepatitis. If the parvo vaccine isn’t working, then neither are the others.

Given all the variables to immunizing a dog, Pietsch said, “These vaccinations are not always a one-size-fits-all.”

Can you kill parvo?

Parvo was once a cheechako, but it has proven to be as hardy as any Alaskan, and it’s here to stay. It can survive for long periods outside its host and live in soils for a year or more. Subfreezing temperatures won’t kill it and may even help it.

Reynolds said the Interior will likely never be rid of parvo, but minimizing it in the dog’s environment can mean the difference between life or death.

“The risk of the infection comes down to two things — exposure to the virus particles and the number of virus particles that the animal ingests when it’s exposed,” he said. “If it’s just a couple, it’s more likely the animal won’t get sick. If it’s a large dose, then not only will the dogs get sick, but often times the severity of the disease will be more intense, and there’s a greater risk of dying from it.”

He said any owner who suspects a dog has parvo should immediately contact a veterinarian because the disease is so contagious that the dog may need to be quarantined. Dogs can get it through contact with another dog or through any surface contaminated with an infected dog’s feces — leashes, harnesses, a person’s shoes or clothing.

Since there is no cure for parvo, he said, a dog’s survival depends on supportive care. Veterinarians can provide the fluids and other life support that the dog needs to keep from dying of dehydration.

Reynolds said owners of a dog that has parvo should use bleach to clean any surfaces that the infected dog has contacted, including bowls, gear and metal fencing. Bleach should be used instead of household disinfectants because parvo can be resistant to the latter. While Reynolds said he could go on with suggestions, he recommends that people with concerns contact their veterinarians to see what works best for their situations.

What is the canine parvovirus?

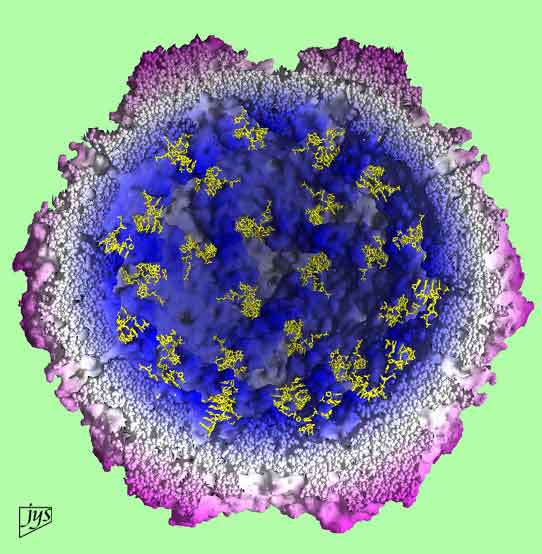

The canine parvovirus is the ultimate moocher. It’s the unwelcome guest that eats one out of house and home. And yet somehow, it stays so small. Parvo is Latin for “small” — the virus is among the smallest.

If a dog without immunity to parvo ingests the virus’ particles, the virus replicates in the dog’s throat and disperses in the blood stream until finding what it needs — rapidly dividing cells.

“Dogs provide the machinery where cells are rapidly dividing — which is in the gastrointestinal tract and in the bone marrow where new bloods cells form. In these areas, cells are dividing and have the means to replicate the DNA within them,” said Hueffer.

Like the cells, the parvovirus contains DNA, Hueffer explained. However, the parvovirus doesn’t have the tools to replicate its genetic material. When a cell divides, it splits into two “daughter cells” and has the machinery to replicate the DNA so that both cells have the same genetic material. The parvovirus hijacks the dividing cells’ machinery and uses it to replicate itself.

This “hijacking” leads to a lot of dead cells and tissue in the gastrointestinal track, which then leads to diarrhea and life-threatening dehydration.

While adult dogs can die from parvo, Hueffer said, puppies are especially vulnerable to the virus in the weeks following their birth. Female dogs that have immunity to parvo — either from a vaccination or from having survived the virus — pass on their antibodies to the virus to their puppies. These antibodies protect the puppies for weeks but eventually die out. Veterinarians don’t know exactly when the antibodies disappear.

The parvo vaccine for dogs will not help a puppy that still has its mother’s immunity, which is why veterinarians give a series of vaccines to hedge their bets. Most veterinarians and researchers believe that the mother’s antibodies clear out of her puppy’s system from 8 to 16 weeks, although some say the antibodies might last up to 20 weeks.

The disease spreads so easily because dogs are such gracious hosts. Sniffing feces and being social with one another introduces the disease to other dogs, which is why kennels or outside areas housing a large number of dogs are at risk for parvo if the dogs don’t have immunity to it.

The canine parvovirus also affects foxes and wolves, but there’s no indication it can affect humans.

Some final thoughts

Arleigh Reynolds: Have a veterinarian come and do these vaccines for you. If that is not plausible because of where you live or because of your budget, then consult with a veterinarian. Make sure you are using the right product and that you know how to store it. Administer it on the proper schedule to give your dog the best chance of getting immunized against the disease.

Greg Pietsch: It’s best to have a veterinarian do the vaccinations. If people are doing their own vaccinations, it’s really important to keep records of where you got the vaccine from and its brand, expiration date and lot or serial number. These are all on the vaccine vial and are usually on a peel-off sticker that you can keep. Record how old the dog was when you gave the vaccine. The records help owners know when the next shots are due. Should the dog become ill, the records can also help veterinarians figure out what’s going on.

Karsten Hueffer: Make sure the animals are healthy when you vaccinate them. If in doubt at all, work with your veterinarian to make sure the dog is healthy and the vaccine is handled right.