UAF's Seward Marine Center celebrates a half-century

March 2, 2021

Alice Bailey

907-328-8383

Onboard was a cylindrical array of sampling containers and instruments that looked a bit more frilly than usual. It was adorned with colorful balloons, including a large “happy birthday” helium balloon, and a bottle of sparkling fruit juice nestled within the cluster of equipment.

Capt. Brian Mullaly stopped Nanuq at an unmarked spot known as Gulf of Alaska Station 1, or GAK-1, in Resurrection Bay. Researchers have been returning there for 50 years, using vessels primarily homeported at the Seward Marine Center. Their measurements form the longest sustained set of temperature and salinity data in Alaska’s coastal and offshore waters.

After arriving, the group popped the cork on the sparkling cider, untied the balloons and got to work lowering equipment over the side of Nanuq to maintain the time series.

The Seward Marine Center likewise celebrated its 50th anniversary in 2020. GAK-1 data and numerous other programs supported by SMC over the past half-century have proved critical for understanding how Alaska’s marine ecosystem functions.

“For the last 50 years, we have provided consistent maritime access to the Gulf of Alaska and the Arctic,” said Doug Baird, SMC’s director and marine superintendent.

Part of the UAF College of Fisheries and Ocean Sciences, SMC’s campus is located on the Seward waterfront near the Alaska SeaLife Center. The centers collaborate on research, funding, and student support and mentoring.

Two state-of-the-art research vessels operated by the university are homeported in Seward’s harbor: Sikuliaq, a 261-foot global class, ice-capable ship owned by the National Science Foundation, and UAF’s 40-foot coastal research vessel, Nanuq.

Seward is a town of about 2,700 people, and SMC’s influence has been substantial. The center is one of Seward’s largest year-round employers. Full-time staff operate research vessels, assist with scientific equipment, maintain facilities and provide other support to scientists who base their fisheries, marine biology and oceanographic research out of Seward.

SMC tries to hire locally, and many crew members have taken courses at Seward’s Alaska Vocational and Technical Center. “The SMC campus is one of the anchors that keeps Seward viable through the winter,” said Terry Federer, director of the Maritime Training Center there.

The K.M. Rae Marine Education Building is an important venue for various community events, such as concerts, election polls, and a popular high school science competition known as the Tsunami Bowl. These activities have depended on generous volunteer support by local people and businesses.

SMC also attracts science teams from around the world, funded by regional, state, federal and international agencies. Their spending bolsters grocery stores, machine shops, shipping companies and other local businesses.

On Dec. 14, 2020, Seward Mayor Christy Terry presented a proclamation commemorating SMC’s 50th anniversary. “SMC is such a benefit to Seward, I just can’t stress that enough,” she said. “The level of academics and skilled technicians connected to SMC raises the caliber of Seward, adds to our population, and allows us to tap into some of that research.”

The beginning

The Alaska State Legislature created the Institute of Marine Science in 1960. It was one of three major research institutions at the University of Alaska at the time. IMS originally had an oceanographic station in Douglas, across Gastineau Channel from Juneau. The station was relocated to the deepwater port of Seward in 1970.

Seward was seen as a better base for research cruises because its road connection allows more reliable, affordable transportation of people and supplies. Scientists had better luck obtaining funding for Bering Sea research with a shorter transit out of Seward instead of Southeast Alaska. The town’s location at the head of Resurrection Bay also is perfect for research in the northern Gulf of Alaska.

Researchers wanted to use the seawater in Resurrection Bay for laboratory studies because it could be pumped from deep water, where it was not affected by surface conditions. People also thought that a less isolated location would encourage faculty and staff to stay long-term.

The move met with political resistance because some lawmakers wanted IMS to stay near Juneau. But eventually it was approved, and IMS faculty, staff and students made it happen.

The research vessel Acona, used by IMS in Douglas, transported crew members and the ship’s equipment to its new home port in Seward. A National Guard cargo plane carried most of the laboratory equipment. Dolly Dieter, an IMS technician at the time, recalled taking the ferry and then driving the remaining lab equipment in a beat-up van.

“It had a hole in the middle of the floor probably 2 feet wide, and I just laid a blanket over it,” she said. “It was December, and I got to Tok and it was minus 50. And then the water pump went out and I was stopping at every stream that wasn’t frozen, getting water to put in the radiator. But those were the things you did. Just keep this thing going.”

Dieter eventually became SMC’s marine superintendent, then director. She was also instrumental in working with NSF on plans for an Arctic ship that would be built after her tenure there.

The new location was called the Seward Marine Station, Seward Marine Center or just IMS. In 1987, SMC became part of the UAF School of Fisheries and Ocean Sciences (now CFOS). Today, IMS is housed within CFOS and serves as its central research organization.

The Seward campus facilities were meager to begin with. The Alaska Railroad’s old repair shop was used as the warehouse. Part of the building was rented out to AVTEC to raise money for the first laboratory space, which is still known as the “yellow building.”

Leonard Weimer became SMC’s first port engineer, after moving there from the IMS station in Douglas. He converted the warehouse boiler room into a machine shop that could support the Acona and was instrumental in keeping the ship and campus facilities running smoothly.

SMC hired Seward residents to support the ship, which established a connection between the center and the community. The center’s finances were spread thin in the early years, but the hard-working faculty and staff have always been dedicated to keeping science operations going.

The laboratory

To replace the first lab, a more extensive laboratory was completed in 1978. In 1982, it was named the D.W. Hood Laboratory after IMS’s second director, Don Hood. The same year, the education building was finished and named after K.M. (Peter) Rae, the founder and first director of the UAF Institute of Marine Science.

CFOS faculty emeritus AJ Paul and his wife, Judy McDonald Paul, came to Seward in 1975 to help design the seawater system for the lab. They stayed at SMC for 27 years.

The high-quality seawater running through the lab could support a diverse range of organisms, from phytoplankton to crustaceans to halibut. Among other things, Paul and McDonald Paul used the lab to observe some of Alaska’s iconic species, such as king crab, halibut, pollock and shrimp, that are harvested commercially but are difficult to study in the wild.

“Crabs are like aliens — they don’t have red blood, they don’t have backbones, they don’t breathe air. To elucidate their life history, you pretty much have to do it in captivity. You can’t do it in situ — they live out too deep and too far away from anybody,” said Paul.

The lab drew researchers from around Alaska and the world who conducted a wide array of experiments there. Graduate students and technicians came from Fairbanks to get their feet wet as scientists. Students stayed from a couple months up to a couple of years developing thesis research on topics ranging from paralytic shellfish poisoning to fisheries oceanography.

A succession of research ships

SMC is a primary docking facility for academic research vessels working in Alaska.

Acona was the first IMS ship homeported at Seward. It was designed for near-coastal research, but that did not stop scientists from venturing farther out.

“Once you got out past Resurrection Bay on the Acona , it was rock and roll,” said Paul. “We called it the ‘blue canoe’ because it rolled and pitched and yawed all at the same time.”

In 1980, the National Science Foundation replaced Acona with the 133-foot Alpha Helix, which was classified as a small regional-class vessel. Scientists once again pushed the ship to the limit, often on long voyages in extreme conditions that made even the most seaworthy sailors ill.

Alpha Helix supported major studies throughout the Bering Sea, Aleutian Islands and Gulf of Alaska. In the 1990s, researchers frequently took the ship to Arctic waters, including the Chukchi and East Siberian seas. One year, Alpha Helix traveled a total of more than 25,000 miles, slightly farther than the Earth’s circumference.

Even though Alpha Helix performed admirably for its size, scientists needed a ship better suited for the open ocean and capable of navigating Arctic sea ice. Scientific teams were becoming larger and more multidisciplinary, and they required more berths, laboratory space and deck space.

In 2001 Congress appropriated funding for a design study of an ice-capable ship. Alpha Helix was used for science operations through 2004 and was sold a few years later.

SMC was left without a ship for several years, so in the meantime scientists used ships based out of other locations and Little Dipper, a smaller vessel homeported at SMC that supported coastal research.

In 2009, after almost 30 years of development and consideration of vessel designs, NSF funded construction of a new ship. It was one of the first projects funded by the economic stimulus package created by Congress known as the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act.

The ship was named Sikuliaq, after the Inupiaq word for “young sea ice,” because it can work in ice up to 3 feet thick, about half a winter's worth of Beaufort Sea ice growth.

Sikuliaq is the only ice-capable vessel in the U.S. academic research fleet. It accommodates 24 scientists, plus two marine technicians and a crew of 20.

The ship extends the research season and possibilities in the Bering, Beaufort and Chukchi seas. Ship time is eagerly sought by UAF scientists and students, as well as researchers from around the world.

“UAF and SMC went from operating a regional class research vessel to operating a global class research vessel, joining the ranks of Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution, Scripps, the University of Washington, and Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory in the academic fleet,” said Steve Hartz, who worked at SMC for 31 years.

As Sikuliaq’s science operations manager, Hartz put together the technical team that designed, installed and integrated science systems aboard the ship. When Hartz retired in 2020, UNOLS recognized his contributions to seagoing research.

Sikuliaq was constructed in Marinette, Wisconsin, about three miles from Hartz's childhood home. In 2014, he sailed on the ship’s maiden voyage from the Great Lakes to Alaska, and helped test equipment and conduct the ship’s first science operations while underway. Sikuliaq arrived at its homeport in Seward in 2015.

Sikuliaq is equipped with sonar, satellite communications, and computer systems capable of supporting a myriad of instruments and gear brought onboard by scientists. Cranes, oceanographic winches and overboarding frames raise and lower scientific equipment. That allows researchers to collect samples, use remotely operated vehicles, and conduct surveys throughout the water column and sea bottom.

Special design features reduce noise transmission in the water to minimize the disturbance of marine mammals, fish and subsistence hunting. Students can experience research activities from afar through the ship’s virtual classroom.

“If you compare the Acona to the Sikuliaq, it’s like comparing a motor scooter to a Cadillac,” said AJ Paul.

In May 2020, Sikuliaq gained international attention as the first U.S. academic research vessel to resume operations after the onset of the coronavirus pandemic. On a cruise operating under strict COVID-19 safety protocols, the science team was reduced to three UAF faculty who worked around the clock and relied heavily on the ship’s crew and technicians.

The cruise was completed without a single COVID-19 case. Sikuliaq’s coronavirus operations plan was shared with other vessels to help them safely navigate the uncharted waters of a global pandemic.

Monitoring the Gulf of Alaska

On Dec. 10, 1970, CFOS faculty emeritus Tom Royer used Acona to collect a series of seawater samples in Resurrection Bay and the adjacent continental shelf. These measurements established the time series that began at GAK-1, which is now one of 15 monitoring stations in a 150-mile transect called the Seward Line.

Royer was primarily interested in temperature and salinity — two of the most important measurements in physical oceanography. Pinning down what was controlling the flow of water in and out of Resurrection Bay could help explain ocean circulation in the Gulf of Alaska.

Scientists and technicians have diligently maintained the data series ever since that chilly December day, even when it meant holding on for dear life in a storm. A marine superstition arose that passing research ships had to stop at GAK-1, and so they did, even after a 30-day research cruise when everyone was ready to get back to Seward.

“The value of long-term monitoring is impossible to quantify. No amount of money can return us to the past to collect observations,” said CFOS oceanographer and faculty member Seth Danielson, who now leads the GAK-1 program.

The creativity of researchers was critical for maintaining the unbroken flow of data. When funding was short, scientists found a way to keep their projects going. For instance, sometimes Acona and Alpha Helix cruises ended early because of bad weather, so those paid ship days could be used to maintain long-term ecological programs and establish new studies.

The scientists’ eagerness to learn about Alaska’s marine ecosystems and the SMC staff’s willingness to support them paid off in 1989 when the tanker Exxon Valdez leaked 11 million gallons of crude oil in Prince William Sound.

UAF scientists and technicians were among the first at the scene. According to the university’s 1989–1990 annual report, Alpha Helix’s schedule was cleared so they could begin researching the spill. The ship even supported a small submarine so they could monitor oil in the water column and on the ocean floor.

Scientists already had an inkling of where and how fast the oil was going to spread, thanks to 20 years of measurements collected throughout the gulf that revealed how water moves along the coast.

Data from GAK-1 and other places helped Royer identify the Alaska Coastal Current. In a paper published by UAF’s Geophysical Institute the same year as the oil spill, he defined the current as a “stream of low-salinity water flowing like a river within the sea.”

The current flows along the coast from Southeast Alaska into the Bering Sea, and then into the Arctic Ocean. “I did a rough estimate of the amount of freshwater flowing into the gulf from the coast of Alaska and found that it exceeds the flow of the Mississippi River,” Royer recalled recently.

The Alaska Coastal Current helps create Alaska’s highly productive fisheries. It disperses invertebrate and vertebrate larvae and provides habitat for juvenile salmon entering the ocean from their natal streams.

And the Exxon Valdez oil spill occurred right in the middle of it.

Knowledge of the current helped Royer talk to communities about how to respond to the catastrophe.

“I was on a teleconference with the City Council of Kodiak a few days after the oil spill, and they were debating as to whether to send their booming material to Valdez,” he said. “They wanted my opinion, and I was sorry to tell them that the oil was headed their way.”

Keeping watch on the waters

Today, SMC supports a growing network of ocean observatories in California, Oregon, the Gulf of Alaska, the Bering Sea, Alaska’s Arctic and Antarctica.

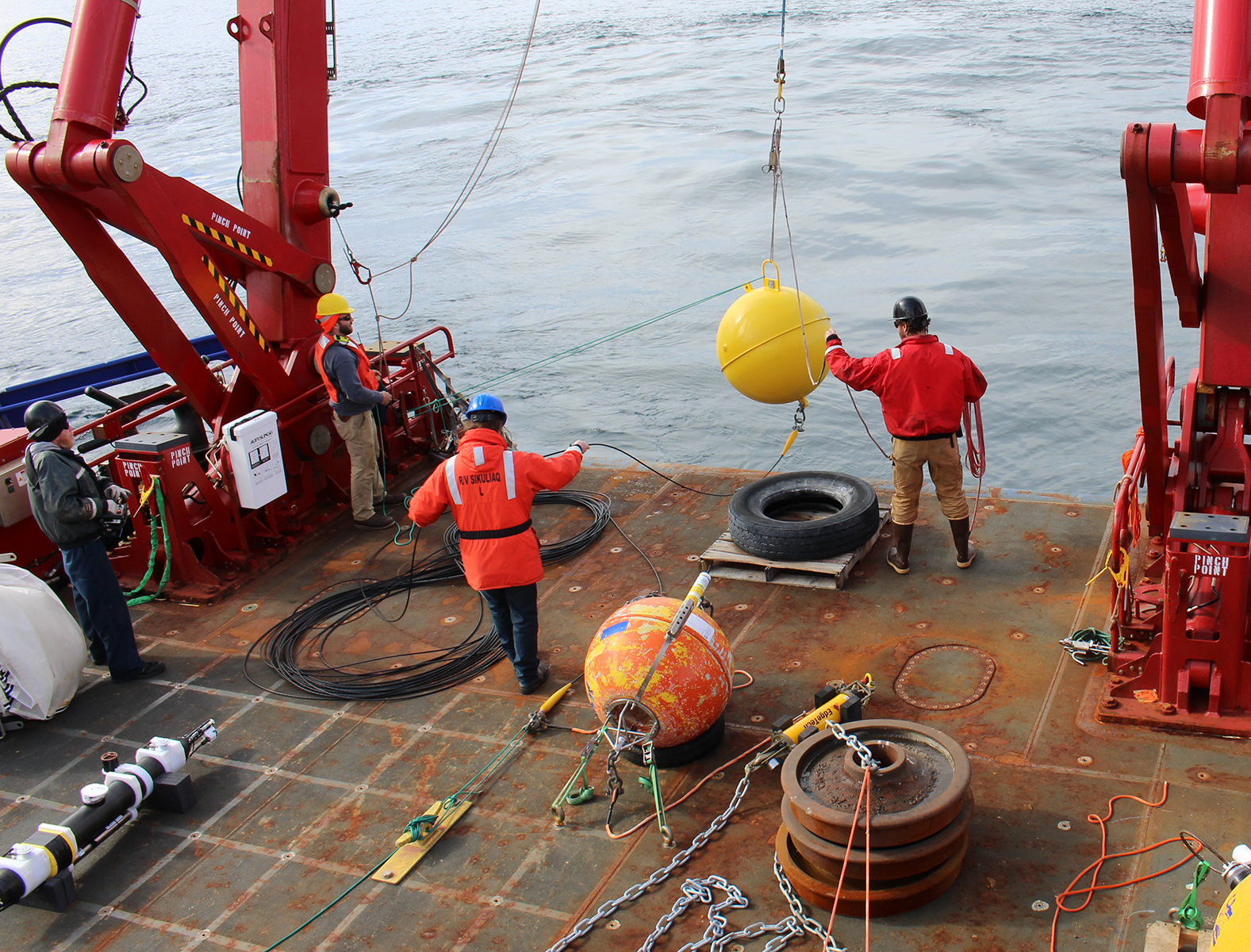

These observatories often rely on anchored systems called moorings, which have sensors and other instruments attached to cables and floats extending from the surface to the seafloor. Moorings can be left unsupervised for a year while they continually log data.

Where early long-term monitoring projects primarily focused on physical oceanography, moored observatories now collect information on many aspects of the ecosystem. They provide year-round context for more extensive ship-based studies, and are handy when important ocean events do not coincide with visits by research vessels.

Mooring systems can be enormous, and they have to be built somewhere onshore. This is where the SMC mooring shop comes into play.

UAF’s mooring operations were first stationed in Fairbanks under the direction of Bill Kopplin, John Smithhilser and then David Leech, the mooring technicians who were responsible for designing, building, installing and maintaining these ocean observing systems.

In 1998, a basic mooring system was installed at GAK-1, an effort guided by

CFOS faculty emeritus Tom Weingartner, who had inherited managing GAK-1 from Royer. At that time, the CFOS mooring shop was moved from Fairbanks to SMC to be closer to the water.

In 2013, NSF funded an expansion of SMC’s mooring shop to accommodate growing interest in year-round oceanographic monitoring, which has only accelerated since then.

“We are a pretty serious staging place for Alaska,” said Peter Shipton, the current lead mooring technician. “We have twice as many instruments now as we did in 2013. Scientists are always trying to get more measurements.”

Shipton loads the mooring cables with sensors and other instruments strategically placed at different depths to accommodate everybody’s needs. Chemists want sensors close to the surface that measure the light and nutrients that fuel phytoplankton growth. Biologists may use sonar equipment to record the presence of fish and zooplankton, or passive acoustic equipment to record noises made by marine mammals. Benthic biologists focus on the depths of the ocean and are interested in catching sinking sediments or taking pictures of the seafloor. And physical oceanographers want well-distributed measurements throughout the entire water column.

Every year, the entire mooring system has to be pulled out of the water so the data can be retrieved and instruments cleaned. Fresh sensors are attached to the cables, and old ones are taken back to shore to be recalibrated. “Turning around” moorings, as this is called, is no small feat. It requires skilled technicians and crew to handle the large, heavy, barnacle-encrusted equipment as it swings overhead while being pulled out of the water onto the deck of a ship rocking in the high seas.

Monitoring programs based out of Seward are part of a larger network of ocean ecosystem observations supported by the North Pacific Research Board, the Murdock Charitable Trust, the Alaska Ocean Observing System, NSF, the Exxon Valdez Oil Spill Trustee Council, and other organizations, institutions and agencies.

Maintaining the continuity of year-round observations is crucial as Alaska’s waters are affected by climate change. For example, the recovered data shows that ocean acidification is a consequence of air pollution. Acidification threatens organisms that have calcium-based shells, like clams and mussels, and the ecosystems and fisheries that depend on them.

Inspiring young scientists

SMC has hosted a regional high school science competition, part of the National Ocean Sciences Bowl, every year since 1998.

UAF was one of the first institutions in the country to participate in the competition, which was designed by the Consortium for Oceanographic Research and Education in Washington, D.C., to help inspire high school students to learn about oceans. Now the Consortium for Ocean Leadership runs the national program.

Judy McDonald Paul was the first Alaska regional coordinator, then passed the role to SMC employee Phyllis Shoemaker when she retired. The regional competition has become quite popular in Seward and has always relied on local volunteers, UAF faculty and support from various businesses.

The first Alaska NOSB was hosted by the newly built SeaLife Center. Now the science bowl is held at SMC’s Rae Building, the high school and other places in town.

Except when there’s a pandemic, Seward experiences an influx of teenagers every spring as small teams arrive from all over Alaska to compete. They answer rapid-fire questions about the ocean and present their research papers. The winning team goes to the national competition, which is hosted at a different participating institution each year. Seward hosted the national competition in 2008.

In 1999, a team named Tsunami from Juneau-Douglas High School won, prompting the news release title, "Tsunami swamps rivals to win 1999 Alaska Region — National Ocean Sciences Bowl.” They won again in 2000 and 2001, and by then everyone loved the catchy name. The organizers eventually named the entire competition the Tsunami Bowl.

The Tsunami Bowl has not experienced any actual tsunamis, but some years have been more challenging than others.

"One year there was an avalanche on the Seward Highway, so half the teams traveling to Seward were stuck on the other side of Moose Pass,” said Shoemaker. “We did the research presentations via videoconference — and that was before it was so easy to do with Zoom. Once the avalanche was cleared, the teams all managed to get to Seward for the quiz bowl.”

Looking toward the future

Even with modifications for the pandemic, it looks like SMC has a busy year ahead.

The first-ever virtual Tsunami Bowl, themed “Plunging into Our Polar Seas,” will proceed in March 2021. Teams from Anchorage, Cordova, Eagle River, Gustavus, Juneau-Douglas, Ketchikan and the Mat-su Valley are participating.

Nanuq will cruise the coast, providing a platform for maintaining long-term monitoring projects and other research, and will be used for a graduate-level oceanography field techniques course. Sikuliaq is scheduled for cruises stretching from Oregon up to the Gulf of Alaska, the Aleutian Islands and the Beaufort Sea.

Designs are being discussed for a new pier that will better accommodate Sikuliaq and other ships of the same size, as are plans for a new warehouse to stage equipment for projects in Alaska and around the world.

And, as usual, SMC’s personnel will be busy orchestrating logistics, building and maintaining mooring and ship-based equipment, facilitating COVID safety protocols for science teams, and performing countless other services.

“The Seward Marine Center has been a central part of our mission as a leader in marine research and education, and we look forward to the next 50 years,” said CFOS Dean Bradley Moran.