View of African drought inspired UAF climate scientist

June 13, 2018

Patty Eagan

907-474-5823

Uma Bhatt always knew she wanted to help people. As a kid, she thought she might become a social worker or a doctor.

While growing up in Pittsburgh, she did particularly well in math and science but had an interest in learning Russian as well. Her father thought she should study engineering.

“You have expensive taste. You like nice things,” she remembered him saying. “So at least get the engineering degree so you can support yourself. Then, if you can make a career out of the Russian, fine.”

At the University of Pittsburgh, Bhatt met David Newman in the honors program while studying engineering.

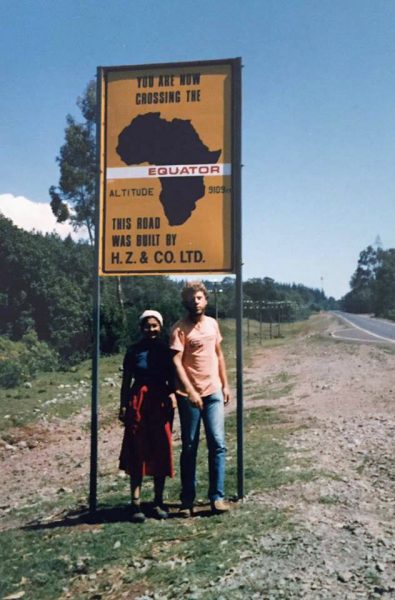

“The two of us were very intellectually compatible, so we started off having rather deep conversations about all kinds of things,” Newman said. A month after their wedding, the two 23-year-olds packed their bags to serve in the Peace Corps in Kenya. The hail storms, beautiful hills and vibrant rainbows completely captured her.

“We lived at 9,500 feet in the western highlands of Kenya, and every day the sunset was amazing,” recalled Bhatt. “Every night, David and I would run to the edge of the hill with our camera and the students would always laugh at us.”

There was a terrible drought in East Africa from 1983 to 1985, their years of service. In Kenya, families had to pay for their children to attend high school. Many of her students only had enough money to pay for a couple weeks of school at a time; seeing their struggles to go to school in a time of such dire food shortages motivated Bhatt.

Bhatt decided she wanted to pursue a graduate degree in meteorology and seasonal weather forecasting after her Peace Corps assignment. Her hope was that governments could use her research to better predict droughts so agriculture could be managed to avoid food shortages.

“We know that if we have information beforehand that it will be dry, our students in Kenya said, they would plant wheat instead of corn," Bhatt said. "So seasonal forecasts can help farmers make decisions to have better economic outcomes.”

While in the Peace Corps, she taught mathematics in the secondary school and completed projects such as building a water tank with the children and local community members. Those two years in Africa gave Bhatt not only a career direction but also a greater understanding that people are the same everywhere. One day, a young student told her a story about a fight she’d had with her brother.

“Just the way the whole thing transpired, that could have been in any country,” she said.

The path led to Alaska

After their return to the states, Bhatt attended the University of Wisconsin and earned a master’s degree studying tropical rainfall and large-scale atmospheric circulation, then a doctorate studying how the ocean and atmosphere interact. Newman pursued graduate studies in physics.

The couple had always been drawn to Alaska. Newman had completed a three-month backpacking trip in the Brooks Range before they met.

“If we didn’t join the Peace Corps, my father was going to give us his pickup truck and we were going to move to Alaska and be teachers,” Bhatt said.

When two faculty positions that were a good fit opened up at the University of Alaska Fairbanks, they leapt at the chance. Bhatt stepped off the plane on a June day in 1998 and immediately felt at home.

Bhatt’s research has everyday applications — atmospheric science studies things that affect air quality and lead to wildfires, as well as methods to better predict the weather.

For example, when state and federal fire managers want to know in March what kind of summer it will be so they can make plans, Bhatt and her colleagues can run simulations to help answer questions about how dry it will be.

Bhatt’s work doesn't revolve around “ah-ha!” discoveries. Instead she likens it to an interlaced GIF. In the early days of the internet, a pixelated picture of something would appear on a computer screen, then slowly a higher and higher resolution image would emerge.

“That’s actually what happens in climate science,” Bhatt said.

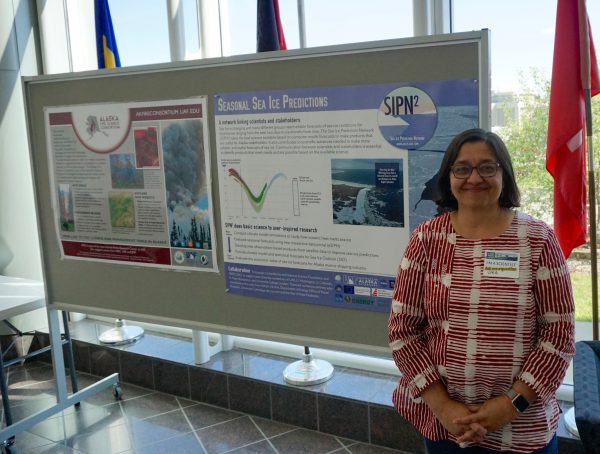

Climate variability is her specialty, so Bhatt uses models as she studies the mechanisms behind complex climate system behavior. One current project in the Yukon-Kuskokwim Delta involves collaborating with an anthropologist and studying snow data and precipitation.

“We started out just by going once a year and showing (villagers) what we found from satellites of what’s happening to the tundra. Then we got lots of ideas from the elders,” she said. Bhatt returns yearly to report and gain new insights, joining forces with the locals.

“It’s listening to people and it’s understanding,” she said.

Return to Africa

Bhatt and Newman have gone back to Kenya twice to visit their former Peace Corps site.

“Our students have done amazingly well,” Bhatt said. Many earned master's degrees and went back home to farm, using newer technology such as solar panels and machines that capture gases from decaying vegetation.

“They used their education to make farms more modern and more efficient; they were not afraid of using new technology,” she said. “It was all natural to them.”

While driving around their old community, Bhatt and Newman chanced upon some of their students, now 20 years older, who were delighted to see them and insisted they come home to meet their children and share dinner — Kenyan hospitality that was impossible to refuse.

Bhatt’s outlook on relationships and people may be reflected in her recent email signature, a quote from Robert Louis Stevenson: “Don’t judge each day by the harvest you reap but by the seeds that you plant.”