Did sea ice help populate the Americas?

People often use sea ice, as seen here off Alaska’s northern coast outside the town of Utqiaġvik, for travelling.

Ned Rozell

907-474-7468

June 7, 2024

Human footprints preserved in mud at White Sands National Park in New Mexico suggest that humans arrived there — possibly via Alaska — at least 21,000 years ago.

No one alive today knows how people got that deep into North America from Asia so long ago. But a team of scientists has proposed winter sea ice as a possible ephemeral highway through and around Alaska and into the New World.

Summer Praetorius of the U.S. Geological Survey in Menlo Park, California, is lead author on a paper in which she suggests that ice that forms on the ocean might have been a platform that helped ancient people migrate southward.

Sea ice — which in winter forms off the coast of western and northern Alaska today — is just what it sounds like: ice that grows on the ocean surface in very cold places.

During winter, sea ice adheres to frigid shorelines of Alaska. It is sometimes fractured and bumpy, but often smooth enough for villagers in far-north communities to drive pickup trucks hundreds of miles from the termination of Alaska roads to their homes.

Praetorius and her colleagues are postulating that the first Americans might have used the same seasonal pathways to avoid giant, crevassed, ice sheets pressing down on North America at the time.

Walking over sea ice might also have presented an alternative to kayaking off the Alaska coast and facing intimidating ocean currents flowing northward.

Using computer models of ancient ocean-current flow, fossil remains of organisms that live on sea ice and several other sources, Praetorius suggests there were two time periods that might have been kind to migrating humans. Those featured a balance of enough sea ice for people to travel upon during winter, as well as the presence of some land that was not under ice.

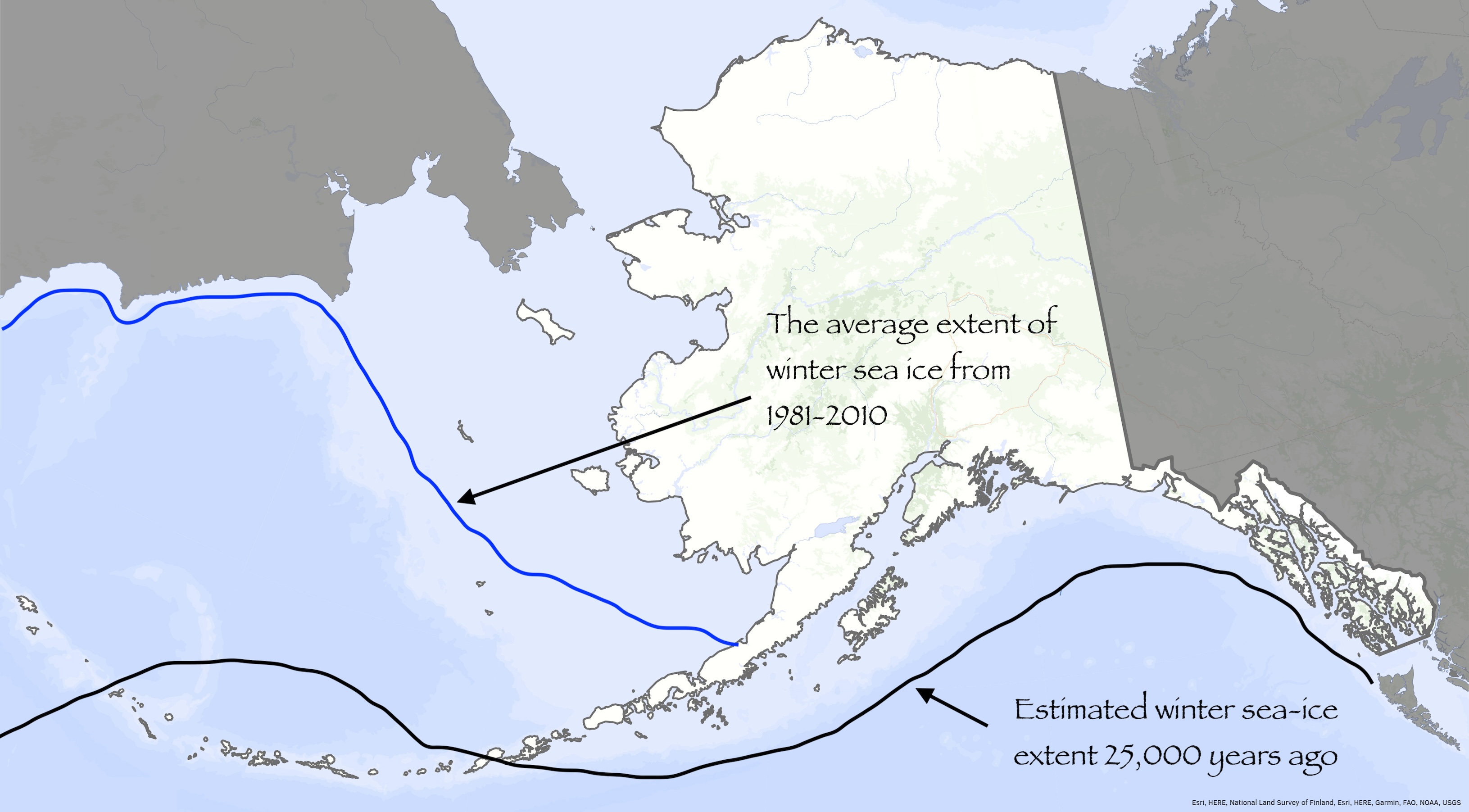

The map shows the median ice extent in March for the period 1981-2010, based on data from the National Snow and Ice Data Center. The line farther south shows the estimated extent of winter sea ice during the last glacial maximum, about 25,000 years ago, based on the paper, “Ice and Ocean Constraints on Early Human Migrations into North America Along the Pacific Coast,” in the journal Environmental Sciences.

Those times were from about 24,000 to 22,000 years ago, and from 16,000 to about 15,000 years ago.

Both of those times were also within a period when the interior of the continent probably was covered with glacier ice. An oceanfront route might have been most feasible for travelers then.

Ancient people might have used sea ice as a bridge to “coastal areas and islands with a relatively traversable surface that doubled as a platform for hunting energy-dense marine mammals,” Praetorius wrote.

During the height of the last ice age, sea ice seems to have formed during winter on the Gulf of Alaska. Very little exists there today, even in winter.

Archeologists have not found ice-age weapons that people would use to harvest seals or bears, which would support the sea-ice pathway theory. Praetorius thinks that may be because those tools are now deep under salt water.

She also thinks her sea-ice highway hypothesis is not mutually exclusive to other theories on how humans came to populate the Americas. Those other ideas include ancient boaters picking their way around ice sheets, the way Glacier Bay kayakers do today. Another is that people scampered southward through an ice-free corridor that might have existed between the giant frozen lobes that flowed over much of North America.

Since the late 1970s, the University of Alaska Fairbanks' Geophysical Institute has provided this column free in cooperation with the UAF research community. Ned Rozell is a science writer for the Geophysical Institute.