Juday awarded George B. Fell Award

Julie Stricker

907-474-5406

Oct. 13, 2021

Glenn Juday, UAF professor emeritus of forest ecology, visits in his office at UAF in October 2021. The Natural Areas Association presented Juday with its highest honor, the George B. Fell Award.

Glenn Juday, University of Alaska Fairbanks professor emeritus of forest ecology,

has received the George B. Fell Award, the highest award of the national Natural Areas

Association and one "reserved for exceptional career achievement."

The award honors an individual for accomplishments in the natural areas profession.

It recognizes an individual’s contributions to research, methods, education or policy

that advance knowledge in the identification, protection and stewardship of natural

areas.

Juday's career has spanned 50 years, during which time he “has been a pioneer in the

field of forest ecology, making a profound impact on the protection and stewardship

of natural areas,” according to the NAA.

The award is given in memory of George Fell, a founder of The Nature Conservancy and

co-founder of the Natural Areas Association. In fact, in 1987 when Juday served as

president of the NAA, he helped establish the award and named it for Fell.

Fell believed that land in its natural state had intrinsic value, beyond development or recreational uses, Juday said. He worked tirelessly to set up systems that would protect natural areas, even as development boomed in the United States following World War II.

Juday said he’s humbled by the award, for which he was nominated by three previous

winners, all peers in his profession.

The recognition by his peers makes it meaningful, Juday said.

“Especially in those early years, it could be a pretty lonely job: You’re fighting

the entrenched institutions and the indifference of the public on critical, critical

issues,” he said. “And the only thing you really have going for you is your utter,

quenching determination to do it because it’s important.”

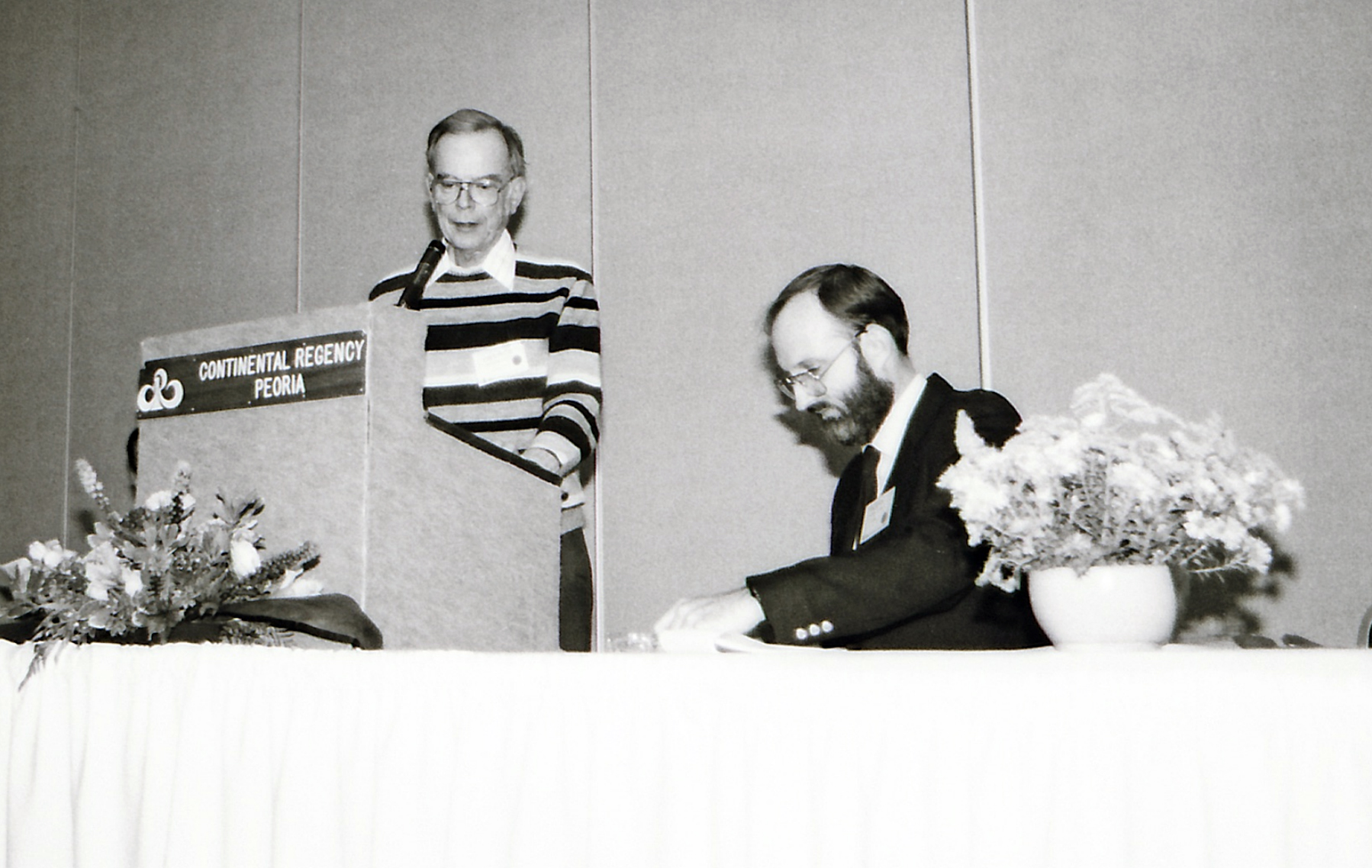

Glenn Juday, right, attends an event with George B. Fell in 1987, when the Natural Areas Association named its highest award for the latter.

When Juday moved to Oregon in the 1970s, the prevailing management viewpoint of old-growth

forests was that they were “cellulose cemeteries” that needed to be cut down so young,

healthy trees could be grown. His first publication tracked the scientific basis for

the benefits of multiple use and sustained yield in old-growth forests, their ecological

importance and rich biodiversity.

According to the NAA, this analysis launched a reappraisal of public land forest management

in the U.S., resulting in a shift from timber production toward strategies to sustain

older forest ecosystem services, biodiversity and nongame wildlife.

Juday also has studied climate change for more than 40 years and said the message

is out that the Earth is warming. However, he said his biggest challenge now is leaping

ahead and telling overenthusiastic activists that “if you misdirect investments and

prematurely put money into inefficient and ineffective so-called renewable or green

technologies ... you’re usurping our potential to invest in what will actually work.”

Juday said his work in the natural areas field is distinct from his research and the

scientific advising work he’s done.

“In the first part of my UAF career, my responsibility for the selection, documentation

and preservation of specific tracts of land important for biodiversity and science

was caught up in the intense reaction against the preservation of the huge tracts

of the national interests lands in Alaska.

“So, I worked instead at the national level to develop and apply new insights into

building conservation and management systems that would sustain the most endangered

elements of biodiversity.”

Within Alaska, Juday quietly made the case for the significance of particular areas.

“I worked hard to develop trust with the land and resource managers,” he said. “So

I considered keeping it all low-key as a success. But I guess the story is out now.”