Moss-killing lichen accelerates carbon dioxide emissions

Heather McFarland

907-687-4544

Dec. 12, 2022

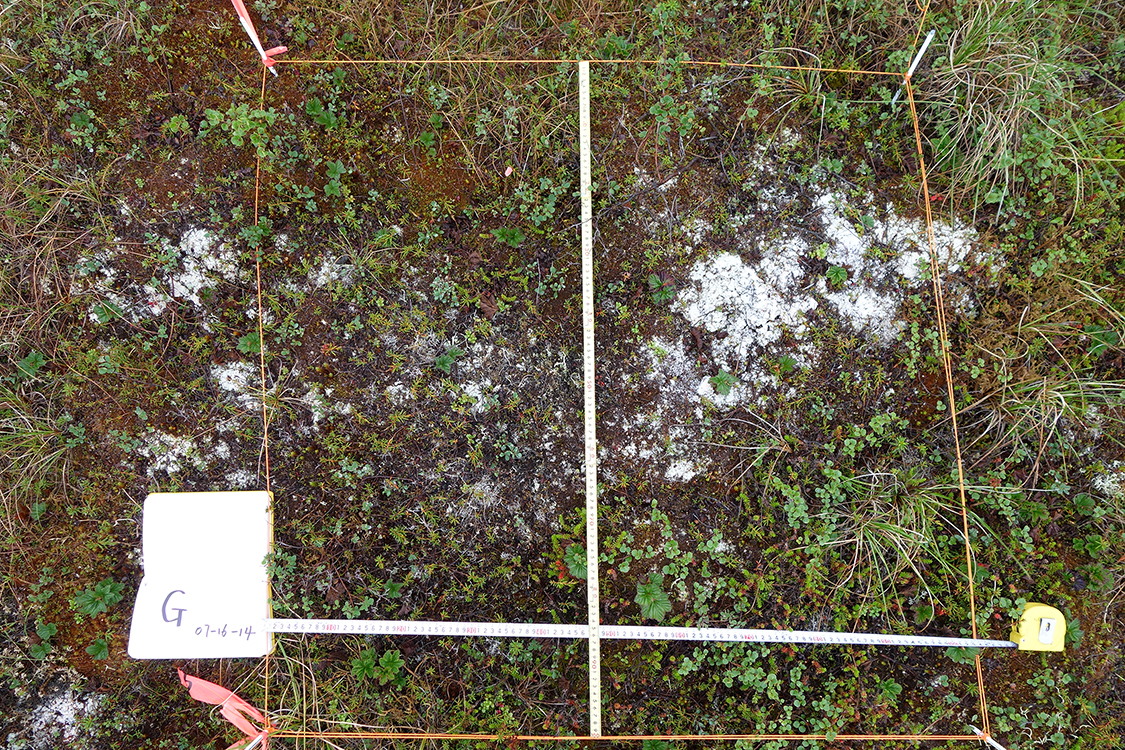

White crustose lichen infests a patch of sphagnum moss in one of Yongwon Kim’s field plots.

Alaskan blueberry pickers are likely familiar with sphagnum moss — the luscious moisture-holding mat that leaves you with a soggy bottom seconds after sitting at a berry bush. As it turns out, sphagnum plays an important role in the boreal forest. It traps moisture at the surface, protecting the permafrost below from thaw.

Yongwon Kim, a permafrost scientist at the University of Alaska Fairbanks International Arctic Research Center, is studying sphagnum-killing organisms called crustose lichens. These lichens form a crust that slowly causes intact sphagnum to wither and die.

From a climate change perspective, these infestations of tiny lichen could be a big problem. The lichen eliminates the protective barrier that sphagnum provides for permafrost — an outcome that makes permafrost more susceptible to changing air temperatures. Also, the decomposing sphagnum releases more carbon dioxide.

“I found the CO2 emission in crustose lichen was higher than intact sphagnum moss,” said Kim. He measured a 34%-40% increase in carbon dioxide release at sites with crustose lichen compared to healthy sphagnum communities.

Arctic permafrost holds an estimated 1,700 billion metric tons of carbon. When that carbon is released during wildfires or from lesser-known sources like dying sphagnum moss and the subsequent permafrost thaw, the atmosphere warms, accelerating climate change.

Kim anticipates that crustose lichen outbreaks may become more widespread as the Arctic and sub-Arctic warm due to climate change. This demonstrates a positive feedback. More lichen releases more carbon dioxide and allows more permafrost to thaw. Both cause more warming, which, in turn, leads to more lichen.