Rugged science on the Southeast coast

Ned Rozell

907-474-7468

June 16, 2022

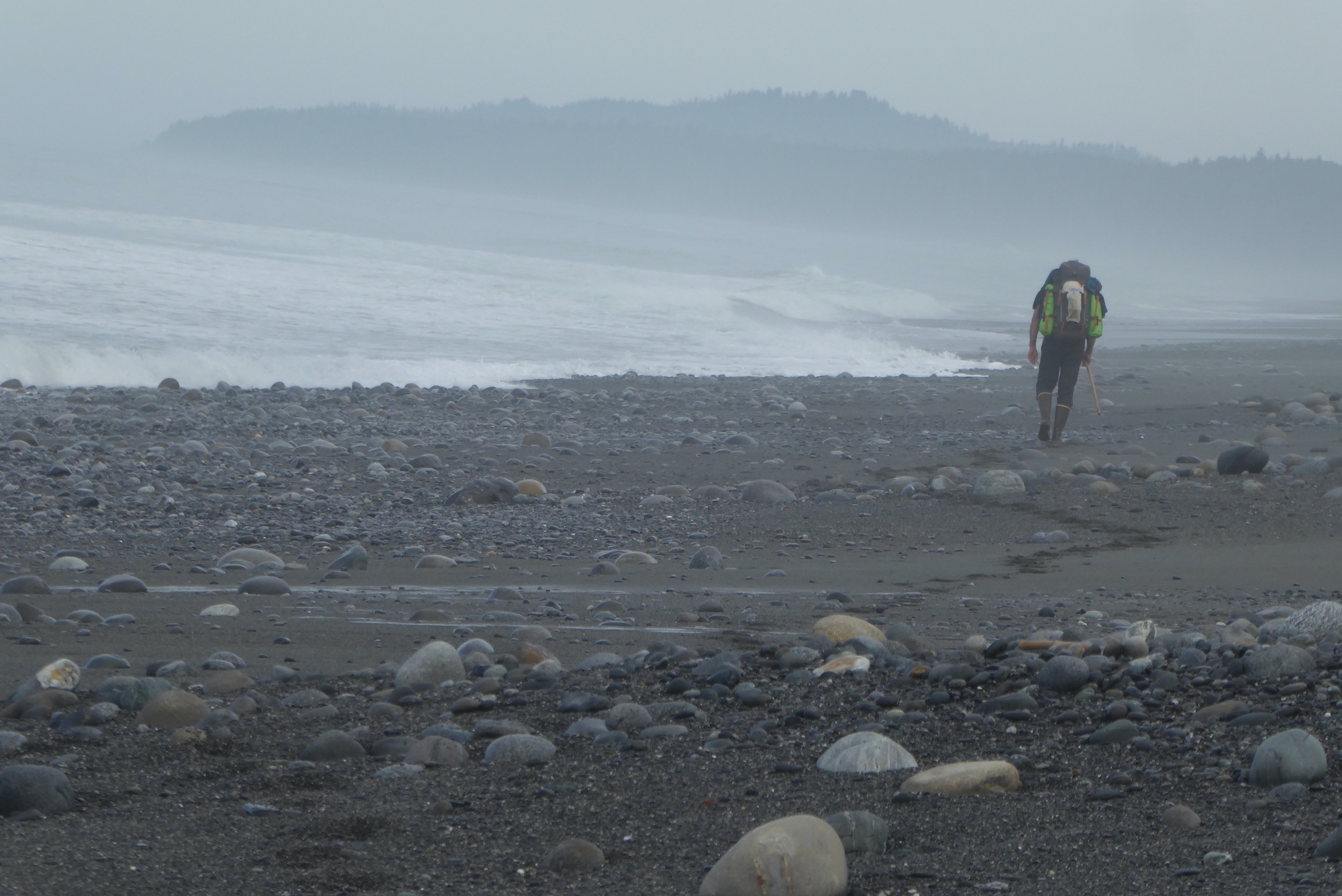

A scientist with a heavy backpack hikes the Lost Coast north of Lituya Bay to reach his study areas.

OVER THE NORTH PACIFIC OCEAN — To the woman wearing earbuds and sitting next to me in seat 7E:

I’m sorry; I did not get to shower before boarding the plane after 12 days of accompanying four scientists in the hills north of Lituya Bay. I will try to keep my arms pinned to my side and lean toward the window.

That’s probably not good enough, but it’s only an hour-and-a-half from Juneau to Anchorage. There, you will be free from the scent of the wild.

If you were available for conversation, I would explain. The leader of our expedition, Quaternary geologist Dan Mann of the University of Alaska Fairbanks, has guided just a dozen people to the spongy terraces north of Lituya Bay in the last 45 years. One reason few have visited is that the high benches are very hard to reach.

We just flew over those plateaus, the 737 passing by them in 10 seconds. On the ground, it took a lot longer.

If you were to pull out those earbuds, ma’am, I would tell you something I found notable about this trip: Over the years, I have gotten wet with scientists on the island of Attu at the far reach of the Aleutians, snowmachined to the giant snow-covered lake called Teshekpuk, and hiked the Valley of 10,000 Smokes as tiny, wind-blown rocks smacked our raingear.

And the last 11 days trumped ’em all for toughness.

Lewis Sharman crosses a fallen Sitka spruce tree over Echo Creek just north of Lituya Bay in Southeast Alaska.

At this point, if you weren’t listening to music, your eyes would dart to the gray hair curling from beneath my baseball cap. Without saying it, you would think, “Yeah, dude, it was hard because you’re old.”

Good observation. There is a lot of mileage on the chassis. But I would offer a slight rebuttal.

The first creek we crossed on this trip filled my Xtratufs with clear water. The second creek forced a scientist to turn back to shore after he waded in to his chest hairs. Plan B to cross that waterway required a six-foot leap off a thick-limbed fallen spruce we used as a bridge. Be mindful not to grab the devil’s club on the way down.

This trip required jungle travel in a land where so much rainfall nourishes so many plants that it is often impossible to see the moss-covered bowling ball under your next bootstep.

There were breaks from that. In the quiet forest that dampens the roar of the nearby ocean on the Lost Coast, we walked with overlong strides on grizzly-footprint ovals pressed into the moss; the bear trails were at the same time neat and unnerving. My job there was to bang a shovel on trees and rocks.

Scientists climb through spiny devil's club on a steep hill north of Lituya Bay in the rainforest of Southeast Alaska.

Did I mention we carried backpacks loaded with 12 days of food? My portion was in an extra bag that hung from my pack like a chimpanzee. That appendage sported a piece of tape with 24# written on it, because that’s what the sea-plane’s company scale said.

Except for the moss and bryophyte specialist who bent to gather 250 samples along the way, our loads got lighter. We ate our food down as the days went on and hung some bags in trees to cache it as we changed camps. We pitched our tents six separate times during the trip, in order to hit the spots the scientists wanted to probe.

The science? I’m glad you asked, because I was out there to record it. But you will have to wait for the next few stories. I’m thinking more now about the grind behind the science, the slow-motion movement in rubberized boots that made the hours tip much heavier on the side of foot travel than data collected.

I’m not going to kid you: Some nights, after eating my bag of dinner, I was too gassed to pull out my notebook and recorder. I just wanted to crawl into my tent on that soggy moss. But it turns out there are a lot of minutes in 12 days. I think I filled enough of the Rite-in-the-Rain notebook to get the goods.

Researchers follow a grizzly bear trail in the forest just off the Lost Coast of Southeast Alaska, north of Lituya Bay.

The star on the Alaska map marks Lituya Bay's location.

One last thing: I called my 15-year old daughter in Fairbanks from Juneau. I told her how I and the one scientist returning to Fairbanks didn’t have time to shower, and how I felt sorry for the person who would soon be sitting at my elbow.

I told my daughter we were going to eat at a diner after a dozen nights of dehydrated meals. I went on to describe everything I just told you (if you had been listening). Her answer showed how much she knows her dad.

“And you loved it, didn’t you?”

Since the late 1970s, the University of Alaska Fairbanks' Geophysical Institute has provided this column free in cooperation with the UAF research community. Ned Rozell is a science writer for the Geophysical Institute.