Scientists look for cause of recent kittiwake die-off

Marmian Grimes

907-460-4750

July 28, 2021

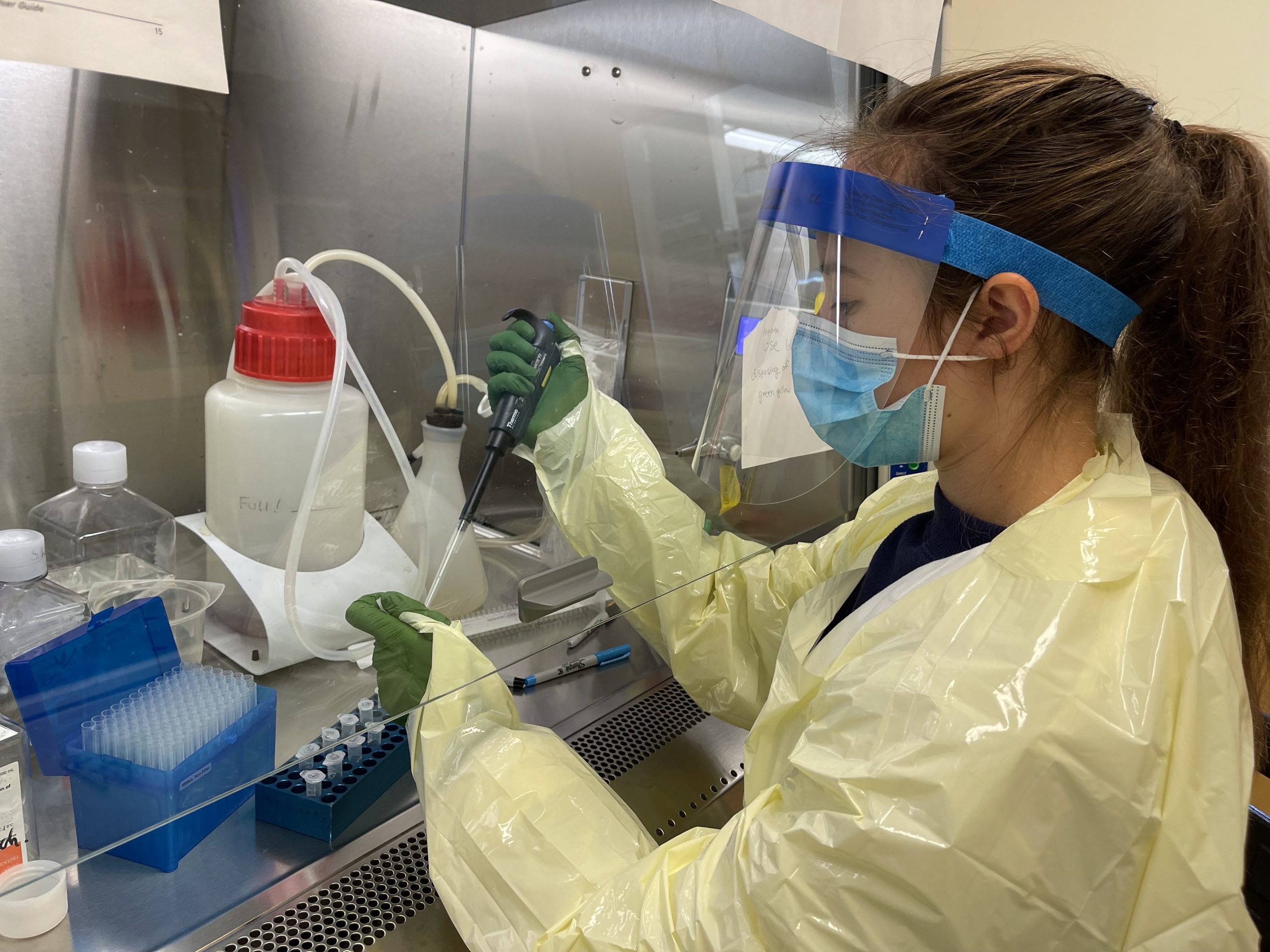

Vera Soloview, a student in the UAA Bortz biology lab, analyses samples for avian influenza earlier in July.

Scientists from the University of Alaska and other organizations are investigating a mass die-off of seabirds on Middleton Island in the Gulf of Alaska.

Middleton Island, located south of Prince William Sound, is a long-term research site run by the Institute for Seabird Research and Conservation. In mid-July, a field crew from McGill University in Quebec was working on the island and noticed an unusually high number of sick and dying black-legged kittiwakes at breeding colonies.

As of this week, several hundred kittiwakes and large gulls have died in the area, according to Alexis Will, a University of Alaska Fairbanks Institute of Arctic Biology scientist who is working on the investigation. She said the rate of death seems to be tapering off.

Will said the response team is optimistic about finding answers about the deaths soon, because they were able to retrieve fresh carcasses and begin testing immediately. The first priority is to check for infectious diseases, she said. That work is already underway, and results should be available to the public within the next month or two. After the initial disease screening is complete, the team will check for biotoxins and other potential causes, she said.

Collaborators on the investigation include the Institute for Seabird Research and Conservation, UAF, McGill University, the University of Alaska Anchorage, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and the U.S. Geological Survey.

“We are really hoping, with all of these collaborations, to model a good response to this die-off,” Will said. “If we can do that, it will provide the foundation for a response plan when these die-offs happen in the future.”

Black-legged kittiwake breeding pair greet each other on "the tower" at the Middleton Island research station.

Mass die-offs of seabirds are becoming more common in the North, Will said, and are often tied to warmer conditions in the ocean. Warmer water temperatures can change food sources or quality and cause harmful algae blooms, all of which can kill birds, she said.

“The die-offs, if you look at them over a broad scale throughout Alaska and the Pacific Northwest, a lot of them are coinciding with warm water events,” she said.

Will said the team also hopes members of the public can help in the investigation. If people see or have seen kittiwakes, gulls, or other seabirds in the area behaving unusually or dead in large numbers since the beginning of the month, they should report that information to the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service at 1-866-527-3358 or AK_MBM@FWS.GOV.

ADDITIONAL CONTACT: Alexis Will, awill4@alaska.edu, 907-752-5005.