Study: Drones effective for surveying tidewater glacier habitat

Jeff Richardson

907-474-5350

March 1, 2023

Court Pegus tests a Phantom 4 drone with Mendenhall Glacier in the background. Pontoon stabilizers were added to his kayak to help it serve as a drone launching pad.

A University of Alaska Fairbanks research project has shown that drones can accurately measure icebergs shed by tidewater glaciers, a potential boon for studying vanishing coastal habitat for seals and other animals in the North Pacific.

Aerial surveys of such icebergs have taken place for decades, but they typically require good weather and expensive fixed-wing aircraft. Drone surveys are much cheaper and more easily deployed.

However, it was previously unclear whether drones could deliver accurate images when both they and the floating icebergs were drifting in winds and currents.

The study found that the drones performed well, recording the height and size of icebergs with mean error ratios of less than 10%.

“We found that drones are very accurate,” said Shannon Atkinson, a professor at UAF’s College of Fisheries and Ocean Sciences. “We demonstrated that even if you have two objects in motion, you’re going to have a level of high accuracy.”

It’s important to better understand tidewater glaciers because such habitat is steadily disappearing amid climate change, Atkinson said. There used to be 200 tidewater glaciers in the North Pacific, but there are only about 50 today.

Measuring icebergs that originate from tidewater glaciers is particularly important for studying habitat for harbor seals, which use them as haulouts to escape predators, care for pups and rest.

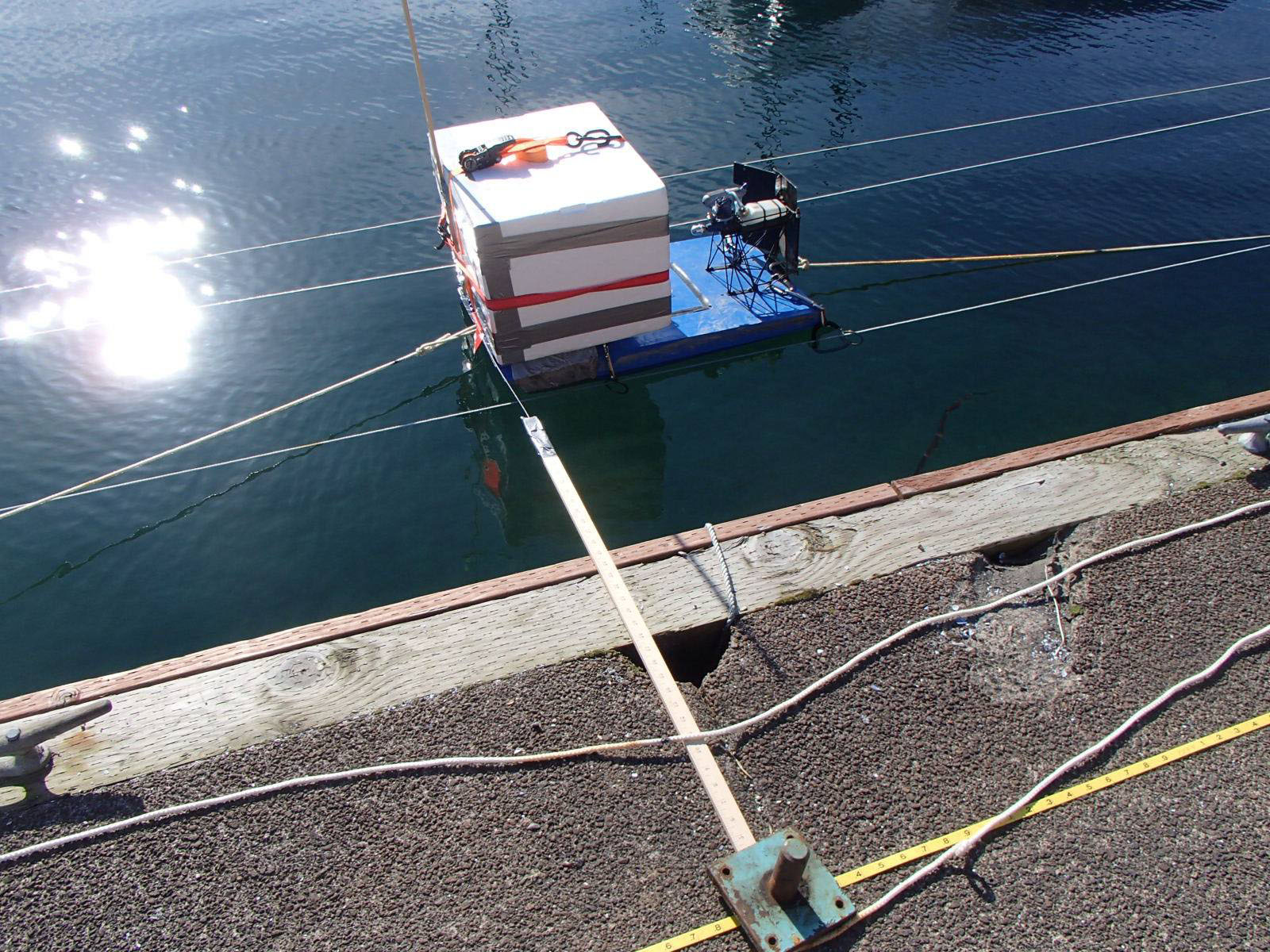

A foam box is rigged with a pulley system, allowing a drone to capture images of it from various distances.

UAF Ph.D. candidate Courtney Pegus tested the drones’ abilities by launching them above the lagoon beneath Mendenhall Glacier in Juneau and taking photographs of icebergs as they calved into the water. Pegus also tested his measurements using a variety of foam cubes, some of which were deployed in a sheltered bay using an elaborate pulley system that controlled their positioning.

The unmanned aircraft performed well with a built-in 20-megapixel camera and a consumer-grade 16-megapixel camera. Drone technology has improved significantly since Pegus began taking measurements in 2018, creating more possibilities for surveying remote habitat, he said.

“Whether you’re talking about mammals, birds, plants, there are just a ton of ways you could use this,” said Pegus, who is including the drone research in his dissertation.

The work was supported by the U.S. Forest Service, which manages the area around Mendenhall Glacier. The Biomedical Learning and Student Training program at UAF, known as BLaST, purchased some of the drones for the study.

The study was published in the December issue of the journal Ecosphere.

ADDITIONAL CONTACT: Shannon Atkinson, skatkinson@alaska.edu

143-23