What Alaskans can learn from the Arctic Report Card

Heather McFarland

907-474-6286

Dec. 13, 2022

Surging Bering Sea waters, driven inland by typhoon Merbok in September 2022, flow through Golovin, Alaska, damaging a third of the homes in this photo by Josephine Daniels published in the Arctic Report Card’s Consequences of Rapid Environmental Arctic Change for People section.

Alaskans can learn much about their state in the 2022 Arctic Report Card released nationwide this week. The Arctic and Alaska are growing warmer and wetter, University of Alaska Fairbanks scientists are at the heart of tracking this and other Arctic changes, and Alaskans are calling for people to work together to address the consequences of climate change.

The Arctic Report Card checks in annually on the state of the Arctic via key “vital signs,” ranging from air and ocean temperature to sea ice and snow. The report also discusses emerging topics like increased Arctic ship traffic. It is produced by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration and released at the fall meeting of the American Geophysical Union.

Precipitation added as a vital sign of Arctic change

This year, precipitation was added as an eighth vital sign in the report card. For the first time, scientists detected a long-term trend showing that Arctic precipitation is increasing in every season.

“We used more than one data set and got the same conclusion — the Arctic is getting wetter,” said John Walsh, the section's lead author and UAF International Arctic Research Center chief scientist. “Up until the last year or two, there wasn't much consensus about trends in Arctic precipitation. Now we've crossed that line and can say that Arcticwide precipitation is increasing, and it's increasing significantly.”

The trend is spottier in Alaska. But October 2021 to September 2022 (reflecting the standard measurement period for annual precipitation) was the second wettest year since 1950. The increases have been mostly in Southeast Alaska and the North Slope, where a 30% increase from the 1985-2014 average is expected by the end of the century. In northern Alaska, the change is enhanced by sea ice loss. A longer open water period makes more moisture available to fall out as precipitation.

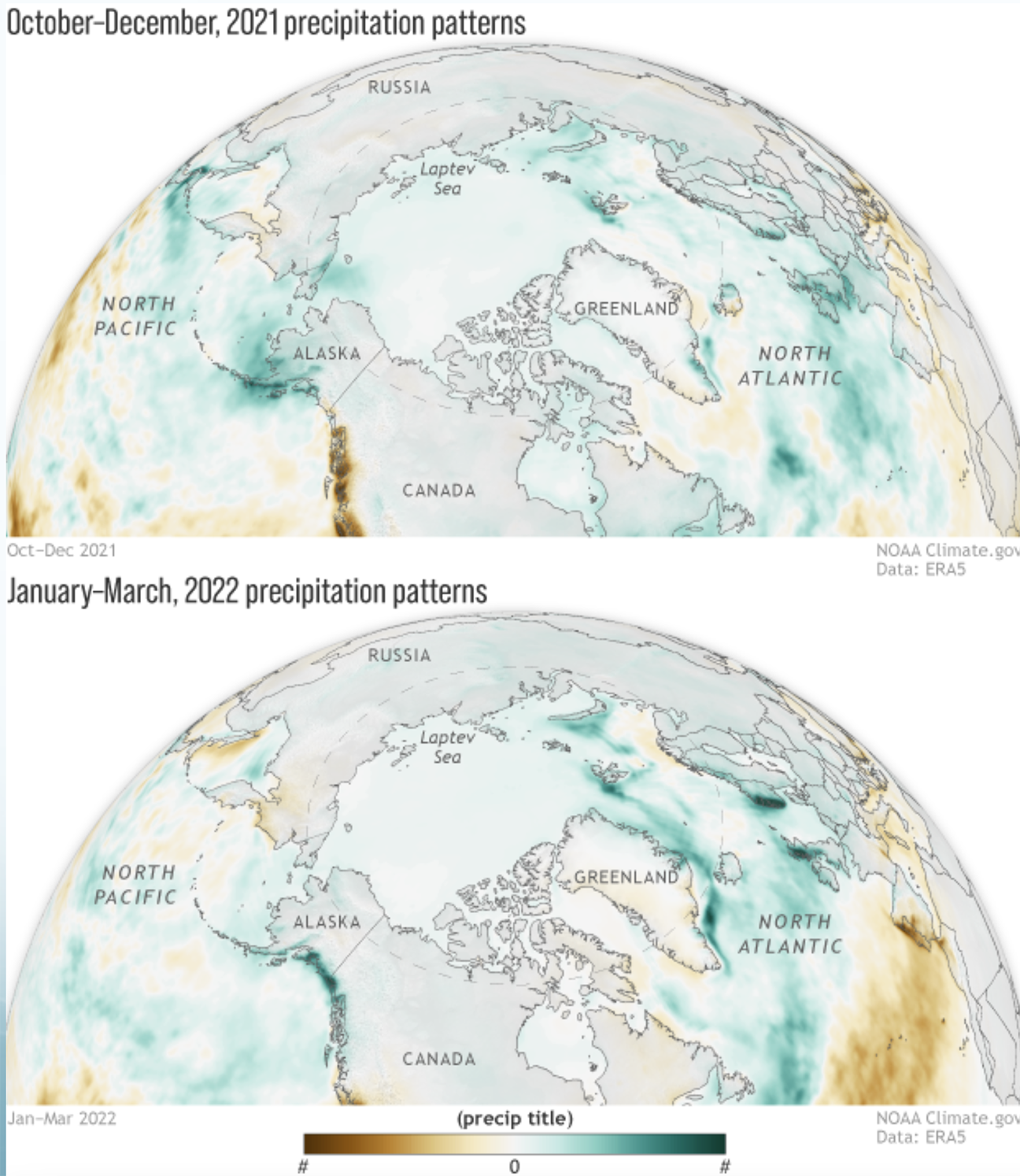

These maps show how total precipitation across the Arctic changed between 1950 and 2022 during fall (October-December, top) and winter (January–March, bottom). The darker the color, the bigger the change: green for increases, brown for decreases.

Within the trend, heavy precipitation events are increasing. Over the past year, Utqiaġvik saw its wettest day on July 26, Cook Inlet its wettest July-August and Fairbanks its wettest December during the “snowpocalypse.”

The change is at the heart of high-impact events, such as wildfire and freezing rain, that Alaskans have been seeing.

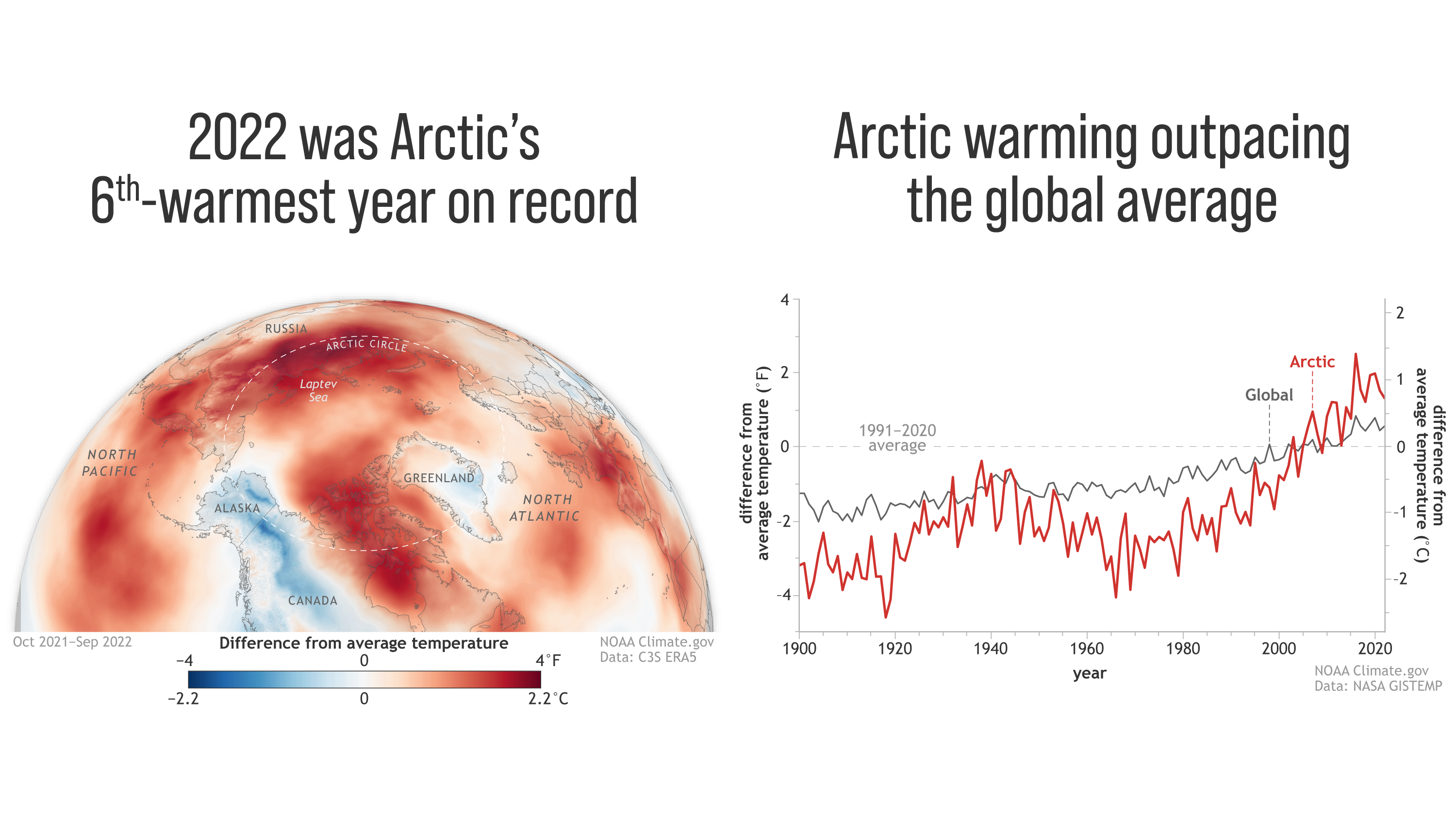

It might seem that more precipitation would curtail Alaska wildfires, but a simultaneous temperature increase complicates the picture. This year’s report card shows that the 2021-2022 water year was the sixth warmest on record in the Arctic. Alaska, however, experienced a relatively cool year, ranking 27th since 1900.

“The catch is that when it gets warmer, evaporation also increases, so you basically accelerate the whole hydrologic cycle. More rain, more evaporation,” explained Walsh. “That does not guarantee a wetter landscape. In fact, if you dig into it, the consensus is that Alaska is more likely to become drier for periods in the summer.”

Even so, deluges of heavy precipitation could put out wildfires, like this summer’s severe June and early July fire season that was squelched by heavy July rains.

The Arctic is also seeing a shift toward more rain and less snow.

“That carries over into the freezing rain problem around Interior Alaska in the winter,” said Walsh. “Last December's event can be looked at as an example of what we might see more frequently down the road.”

Human consequences of climate change

Recognizing that Arctic change extends beyond environmental elements, this year’s report card included a discussion on climate consequences felt by Arctic peoples. The essay was informed by a recorded oral history of Ahtna Dine' storyteller Wilson Justin about how climate change has impacted him and his community, as well as his experience of the world.

Justin shares powerful insights about how people can overcome the colonial divide, reach across languages and cultures, and move forward to tackle climate change.

"Climate change in today’s vernacular no longer is climate change. It’s a done deal,”

said Justin in the oral history. “We’re just gonna have to figure out how we’re going

to speak to each other in terms of not only rebuilding, but what it is we are going

to rebuild."

Justin’s account was combined with perspectives on human impacts from over 40 authors.

The effort was facilitated by the Study of Arctic Environmental Change, a program

directed by IARC’s Brendan Kelly and Athena Copenhaver.

Led by UAF scientists

Walsh, Kelly and Copenhaver are among 12 UAF researchers contributing to the report card this year. Their leadership is not new; UAF scientists have been editors and authors of the report since its inception in 2006.

This graphic from NOAA shows warming in the Arctic.

Jackie Richter-Menge, affiliate faculty with UAF’s Institute of Northern Engineering, served as a lead editor from 2006-2019 before passing the baton to IARC’s Rick Thoman, who has been an editor since. Thirty-five others at UAF have authored sections within the report over the years.

“We can give the information for Alaska better than anyone. We have people who work on all these different variables,” said Walsh, who has been an author all 17 years of the report's existence. “So I think UAF is a natural nucleus for input, at least for the Alaska side.”

This year’s UAF cadre again includes Thoman as an editor. Authors, grouped by the topics on which they contributed, include: Tom Ballinger (lead author), Walsh, Thoman and Uma Bhatt on surface air temperature; Walsh (lead author), Rick Lader and Ballinger on precipitation; Melinda Webster on sea ice; Bhatt and Donald Walker on tundra greenness; Todd Sformo on North America’s Arctic geese; Derek Sikes on Arctic pollinators; Gay Sheffield on seabird die-offs in the Bering and Chukchi seas; and Kelly and Copenhaver on the consequences of rapid environmental Arctic change for people.

IARC’s Quick Guide to Climate Reports explains how the Arctic Report Card is connected to other major climate reports.

ADDITIONAL CONTACTS: Athena Copenhaver, Study of Environmental Arctic Change, aecopenhaver@alaska.edu, 831-601-6717.