Work by UAF researchers, NASA aids Hurricane Ida response

Rod Boyce

907-474-7185

Sept. 16, 2021

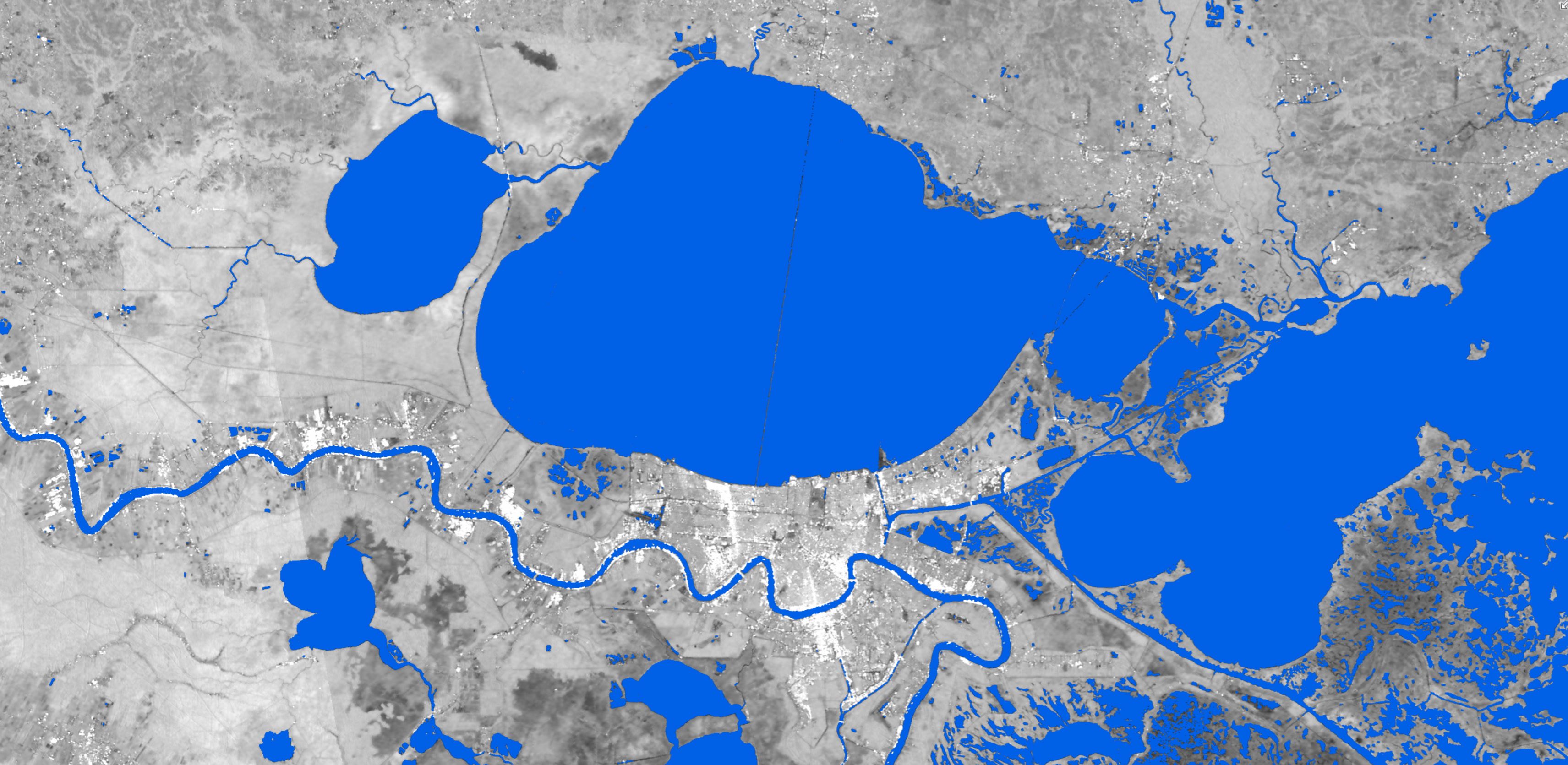

Surface water appears in blue around New Orleans on Aug 29, 2021. Water extent data is derived from synthetic aperture radar. The background image is also built from SAR data downloaded and analyzed by the Alaska Satellite Facility, part of UAF's Geophysical Institute.

Federal emergency managers needed detailed information as Hurricane Ida approached Louisiana at the end of August. In Fairbanks, 3,400 miles away, scientists specializing in remote sensing were able to provide that information using technology they created to speed up the process.

The task grew from an important partnership between the University of Alaska Fairbanks and NASA, which provided a four-year grant in 2019 to make synthetic aperture radar data useful in the response to weather-related disasters. The effort is led by remote sensing professor Franz Meyer with the UAF Geophysical Institute.

“There are many other groups with similar remote sensing skills, but they don't have the capability to create image products operationally across the vast areas that need to be monitored for an event like a hurricane,” said Meyer, who also teaches in the UAF College of Natural Science and Mathematics.

“The magic is in the combination of the remote sensing of hazards expertise at UAF, and with partners at NASA’s Marshall and Goddard Space Flight Centers, along with the image archive access, computational skills and cloud computing experience available at the Geophysical Institute’s Alaska Satellite Facility,” he said.

That “magic” allows the scientists to develop new image products and scale them up to run efficiently on a regional to continental scale, he said.

One of the developments came quickly into play with Hurricane Ida: a computer algorithm

that automatically highlights surface water in satellite imagery and extracts it so

that it stands alone.

It’s the result of a question asked by the Federal Emergency Management Agency during

Hurricane Harvey in 2017: “Where is the water?”

“How they had been doing it up to that point was either with aircraft, with people

on the ground or with optical satellite data,” said Lori Schultz, with the Earth Applied

Sciences Disasters Program at NASA’s Marshall Space Flight Center in Alabama and a

project partner with UAF.

“Optical satellite data is restricted by cloud cover and Hurricane Harvey had a lot

of cloud cover for multiple days after landfall, making aircraft and traditional satellite

observations difficult,” she said.

UAF and NASA scientists went to work during Hurricane Harvey to answer FEMA’s question.

They came up with a rudimentary, manual method as they used synthetic aperture radar

to peer through clouds.

Through hurricanes and flooding events since then, scientists at the Geophysical Institute

and NASA have worked with FEMA to improve the process — bringing it to today’s fully

automated version.

How it works

Whether manual or automated, the process starts with synthetic aperture radar sensors

aboard the European Space Agency’s two Sentinel-1 satellites, launched in 2014 and

2016. The sensors image the Earth at wavelengths that make clouds, fog and rain transparent,

meaning the ground can be imaged around the clock and that an event like a hurricane

won’t interfere.

The raw satellite data has more information than FEMA officials would need while dealing

with Hurricane Ida, however, so they were processed using the algorithm to highlight

surface water.

Once processed, the Alaska Satellite Facility distributed those images to disaster

managers as the hurricane came ashore in Louisiana and then headed northeast as far

as the New England states. UAF and NASA scientists spoke daily with FEMA officials

to present and interpret the latest imagery.

The Alaska Satellite Facility is involved because it is the only one among NASA’s Distributed Active Archive Centers that specializes in synthetic aperture radar data.

Hurricane Ida was the first use of the automated process in a hurricane response.

Because of that automation, hundreds of images can now be produced in a short period — as was done in the Hurricane Ida response.

“We can do that quickly because of the way we implemented all the techniques,” Meyer said. “If we need to process 500 images right now, we can have it done within 20 minutes.”

The images are limited only by how often the polar-orbiting satellites see a disaster-affected area as the Earth rotates beneath them. Depending on when the satellites pass over, images may be available immediately after an event or only several days later.

What’s ahead

As more satellite sensors become available, disaster information from spaceborne sensors will grow more timely. New specialized computer algorithms could be created to analyze disasters other than hurricanes.

The process will improve further in 2023 when NASA launches NISAR, a radar-based Earth observation sensor being developed in partnership with the Indian Space Research Organization. Meyer is on the science team for that mission, and the Alaska Satellite Facility has been named the archive and distribution point for the data.

“We have been getting ready for NISAR on many fronts, including leading development in cloud computing technologies to ensure the data are delivered quickly to the waiting scientists and disaster responders,” said Nettie La Belle-Hamer, director of the Alaska Satellite Facility and UAF’s interim vice chancellor for research. “We are ready,” she said.

ADDITIONAL CONTACTS: Franz Meyer, fjmeyer@alaska.edu, 907-474-7767; Lori Schultz, Marshall Space Flight Center, lori.a.schultz@nasa.gov.

NOTE TO EDITORS: Images and a longer version of this press release are available at gi.alaska.edu.