Music that Comes from the Cold

Catherine Madsen

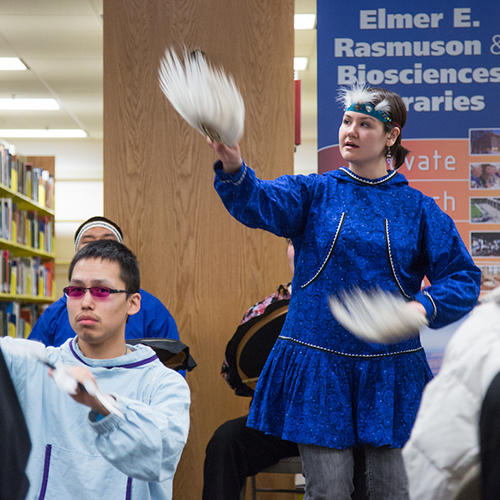

In the summer of 1983 the Inuit Circumpolar Conference held its third general assembly

in what is now Iqaluit, Nunavut (then on the maps as Frobisher Bay, Northwest Territories).

Now known as the Inuit Circumpolar Council, the ICC was founded in 1977 by Eben Hopson of Barrow (now Utqiaġvik), and is the

political voice of Inuit worldwide. The conference included a feast of old and new

music, from traditional drumming and dancing to electric guitars, by performers from

Alaska, Canada and Greenland. Thanks to YouTube—and thanks especially to the Inuit Art Quarterly, which embedded the videos in a recent article—we can watch highlights of the music at this exhilarating conference. In addition

to the commonalities among the performers, it’s interesting to see the striking differences,

especially the distinctly European high-culture style (via Denmark) of the Greenlanders.

In the summer of 1983 the Inuit Circumpolar Conference held its third general assembly

in what is now Iqaluit, Nunavut (then on the maps as Frobisher Bay, Northwest Territories).

Now known as the Inuit Circumpolar Council, the ICC was founded in 1977 by Eben Hopson of Barrow (now Utqiaġvik), and is the

political voice of Inuit worldwide. The conference included a feast of old and new

music, from traditional drumming and dancing to electric guitars, by performers from

Alaska, Canada and Greenland. Thanks to YouTube—and thanks especially to the Inuit Art Quarterly, which embedded the videos in a recent article—we can watch highlights of the music at this exhilarating conference. In addition

to the commonalities among the performers, it’s interesting to see the striking differences,

especially the distinctly European high-culture style (via Denmark) of the Greenlanders.

We also have online access to an obscure and important collection of Nunamiut music. Helge Ingstad, whom I mentioned briefly in the last post, recorded 141 songs during his stay with the Nunamiut in 1949-1950. On returning to Norway he shared his recordings with composer and music theorist Eivind Groven (who was more or less the Norwegian Vaughan Williams), who transcribed the songs and analysed their tonal and rhythmic qualities. The Alaska Native Language Archive has a signed copy of Groven’s typescript, and has posted it as a pdf. A selection of 97 of the songs was released in 1998 on the 2-CD set Songs Of The Nunamiut: Historical Recordings Of An Alaskan Eskimo Community. It’s very unusual to find this set for sale, and still more unusual to find an affordable copy, but fortunately for those at UAF the Rasmuson Library owns it.

A momentous recent event in circumpolar ethnomusicology was the 2022-2023 exhibition TUSARNITUT! La musique qui vient du froid/Music Born of the Cold, curated by musicologist Jean-Jacques Nattiez for the Montréal Museum of Fine Arts. (The show also traveled to the Royal Ontario Museum in Toronto.) Nattiez focused on two major genres of Inuit music, drum dancing and throat singing, and in addition to many audio and video recordings he included over 200 works of visual art—sculptures, prints, drawings, masks—representing Inuit musicians, dancers and singers as well as shamanic rituals and scenes of daily life.

The catalogue of the exhibition, published in French by Les Presses de l’Université de Montréal, is a monumental achievement. Like Eivind Groven, Professor Nattiez has thought deeply about music analysis, attempting to develop a system something like linguistics for the study of music, and the book features detailed structural analyses of drum-dancing chants and throat singing, as well as providing a very thorough historical context for the development of Inuit music and its survival in the face of many threats. The book focuses on Alaska, Canada and Greenland, but closes with a wider discussion that includes the indigenous peoples of Siberia and even Japan, where the Ainu form of rekukkara strongly resembles Inuit throat singing.

To supplement the text, the book includes many references to audio and video files that can be found online. Some have YouTube or other URLs, and some are available on the publisher’s website. The latter is an extraordinary resource, with well over a hundred archival recordings and videos of throat singing, drum dancing, shamanic songs, curing songs, lullabies, and other forms of song from around the circumpolar North.

As someone with spotty French (I can more or less manage expository prose, but as soon as things get subtle and interesting I’m out of my depth, as with the discussion on p. 225 of how Sedna came to be so often portrayed as a mermaid, or the very sophisticated analysis in Chapter 9 of the vocal technique and structure of throat singing), I’m hoping that an English translation of the catalogue is in preparation. Meanwhile actual Francophones, in addition to being able to read the book competently, can watch an interview with Professor Nattiez on Facebook. (Click on CC in the lower right of the video for English auto-translation if you need one, but be aware of the limitations of auto-translation: this one has no idea what to do with “chant gorge” (throat singing) and renders “estampes” (prints) as “stamps” and “genres” as “genders”. That’s why it’s called artificial intelligence.) Whatever the level of your French, explore the catalogue for its stunning visuals, which include works by some of the greatest Inuit artists. You can find it in the Alaska Collection at the Rasmuson Library.

Resources

Click the links below to learn more about people and places mentioned in the article.

About the Author

Catherine Madsen is a writer, singer and folk harper now living in Michigan. The three years she spent in Fairbanks as a child (1962-65) were a turning point in her life, and she established the Circumpolar Music Series as a gift of gratitude.