Butterflies

The legacy of Kenelm Philip

A passion for collecting

The insect collection at the University of Alaska Museum of the North is fairly new. It began in 2000 with money from the National Science Foundation. Before scientists began systematically collecting and cataloging specimens from Alaska, not much was known about the state’s smallest residents. Except for the butterflies.

For decades, Kenelm Philip had been collecting them in Alaska, intent on solving the great butterfly mystery. Every year he returned to his favorite spots along the highways and in the boreal forests of Alaska. He drove a yellow pickup with an “INSECT” license plate. He founded the Alaska Lepidoptera Survey and amassed the second-largest collection of arctic butterflies and moths in the world – more than 83,000.

When Philip arrived in Alaska in 1965 to work as a radio astronomer, scientists couldn’t agree on some basic questions. How many moth and butterfly species were there in Alaska? What was their distribution? How were they related? Soon he added looking for Lepidoptera to his passion for listening to the stars.

By the time Entomology Curator Derek Sikes met Philip, he had been collecting and studying butterflies for forty years, searching for the tiny insects in the vast arctic. Philip funded the operation entirely, accepting donations of supplies and relying on the generosity of colleagues to share space on their scientific expeditions

Sikes came to Fairbanks in 2005 and was invited to the Philip home. “Before I met him, I’d heard that he was eccentric. To have 83,000 butterflies in your house, you’d have to be a little different. But he had a great sense of humor and was interested in so many things, from fractals to microscopes.”

Sikes saw countless specimens stacked in the Philip house, labeled and catalogued. Still more were waiting to be processed. He was impressed with the methods Philip used to prepare the butterflies. “As much as he cared about the data, he loved the specimens. He was meticulous with them. It was amazing to watch him spread the wings of these delicate animals. I work with beetles. They are the tanks of the insect world. I never learned those skills.”

The museum’s former curator of insects agrees. Jim Kruse first met Philip on-line 20 years ago when he was a master’s student. In 2000, when a position to establish the insect collection opened up at the UA Museum of the North, Kruse called Philip with more urgent requests for information about Alaska and entomology in the boreal and arctic regions.

Kruse saw that Philip’s techniques were unique. “There is no doubt that Ken had a driving passion since he was a little boy, but what made him different was that he also had a passion for good science. He was a butterfly expert in every facet of their life cycle and habitat. Each species in his collection was arranged according to biogeographic data, which really is rare.”

Before Sikes accepted the curator job, he went into the field with Philip. “I collected my first Alaska specimens with him.”

When Philip passed away on March 13, it was unexpected. He was in excellent health for an 82-year-old. He’d spent the winter working on his collections, maintaining his correspondence, and planning a robust field season. His passing was mourned by many, but equally important was the need to take care of his legacy – the collection.

A team of helpers mobilized. The mission, to get the specimens to the museum in the best shape possible. The objects were destined for collections at both the UA Museum of the North and the Smithsonian Institutes. Many other specimens had been collected on federal land and belonged to the National Park Service.

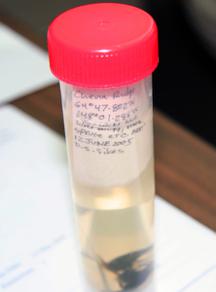

While Sikes was working at Ken’s house packing up the collections, he found the vial of wasps and tiny insects labeled in his own handwriting, the specimens he had collected with Philip on that summer day in 2005. “It was just sitting there, on a shelf.”

More than butterflies

Butterflies and moths weren’t the only things Philip collected. He had an interest in microscopes and books. He loved Macintosh computers so much he never discarded the older models. Piles of accumulated objects became the rooms of his home. He even accumulated telephone calls, keeping in touch with many friends and volunteers.

Sikes talked to him regularly. “Not too often, maybe twice a week. He loved calling people. If a couple of weeks went by without hearing from him, I would be surprised. And he didn’t just call to shoot the breeze. He always had some news to share.”

Philip communicated with more than 600 volunteer collectors, helping to amass specimens from across the North, including all regions of Alaska. His collection also held butterflies from faraway locations, such as Puerto Rico and Ethiopia.

Kathryn Daly’s relationship with Ken Philip began in much the same way. Daly is a research tech at UAF’s Institute of Arctic Biology. She met him in 2011, after sending the museum several caterpillar and butterfly photos taken at the Toolik Field Station in the foothills of the Brooks Range. “Professor Sikes forwarded them to Ken, who identified the species and shared his own high-quality images to confirm my guesses.

“When I finished my undergraduate work, I spent a summer in Colorado working on an alpine climate project. I took photos of butterflies and sent them to Ken. Even when they weren’t an Alaskan species, he loved to share sightings.”

When Daly showed an interest in learning how to prepare museum specimens, Curator Derek Sikes offered her a batch of butterflies to bring to Philip. She spent the past winter visiting him frequently, learning his techniques. The care which Philip took with each of the specimens has astounded everyone who worked with him. And although it was well-known that he was an excellent scientist; he was also a skilled artist in preparing museum-quality specimens, Daly said.

“Not only were the rows of butterflies arranged in perfectly straight columns with wings positioned symmetrically on every specimen, Ken also took the time to straighten every head, arrange each leg, and even positioned the antennae to appear in the most natural curve possible.”

Daly was part of the “friends of Ken” who helped move the massive collection to the museum. They transported scores of drawers and many, many cabinets, boxes, and objects. They each stopped to marvel at his work, admiring the labels with tiny writing, the obvious care he took with each entry.

Sikes said the Park Service knew that Ken had a sizable amount of specimens, so they expedited funds to catalog the collection. The specimens will each receive a unique barcode linking them to database records of their associated collection information. Philip was meticulous with his field notes. There are also 20,000 slides that accompany his specimens.

“He took photos of his collecting locations,” Sikes said. “These will be a great historical record of the habitats as our climate changes.”

Daly says working at the museum will be a way to honor the amazing work that Ken did. She’s still mourning the loss of the time she was expecting to spend with him this summer, but is placated by the knowledge that she will be able to help ensure that his legacy is preserved.

“His contribution to the knowledge of Alaskan Lepidoptera is unrivaled,” she said. “He was the top expert in this state, and I hope that by incorporating his collection, global researchers can learn from his work, and museum visitors can appreciate the incredible effort that Ken undertook in running the Alaska Lepidoptera Survey.”

A lasting legacy

In his will, Ken Philip left 90% of the collection to the Smithsonian. That is 83,156 specimens. Sikes said we don’t know what the final division will be. “The National Park Service will have a voice. We’re not sure yet whether specimens collected on their land will be required to stay in Alaska. What I know is that we all want to work together to make sure the collection is as valuable to science as possible.”

The collection is a national treasure. Philip filled a huge void in our biological knowledge of the butterflies and moths of the North. They were poorly documented until he started working on the survey. This area is a very large part of the globe, yet the Smithsonian did not have it adequately represented in their collection.

Kruse said Philip did not donate butterfly specimens to the museum while he was alive. “But he did prepare for the future by making arrangements. I know that Ken wanted a large portion of his collection to go to the National Museum, but after the university committed to hiring a curator of entomology who would also teach, Derek and I were able to convince him that a good portion should reside in Alaska.”

Even though he hadn’t yet donated any butterflies to the UA Museum of the North, Philip is already well represented in the collection. When Sikes checked the online database Arctos, he quickly found 1,232 Philip specimens – bumblebees, wasps, flies, and more.

In the meantime, he kept all the butterflies with him. Sikes says he did what every entomologist dreams of doing. “The collection was a part of his life. It was all about efficiency. All the data and information was right there with him. The specimens were kept in a fireproof concrete building. If his house burned down, his collection would be safe.”

Philip planned to publish a book about his work. His colleagues are now committed to working together to make that happen, Sikes said. “We’ll preserve as much of his photos and data as possible. We may have to augment his work, but we’ll get something published that will respect his scientific vision.”

At a recent Lepidoptera Day at UAMN, Sikes pulled out drawers of unidentified butterflies in the collection. Philip was there. He identified 30 species that day. It was January 14, 2014.

That was the last time Sikes saw him. “He left so many things unfinished. Many of his specimens aren’t fully prepared. We plan to take photographs of entire drawers. We want to preserve the immensity of the collection and the internal organization before we disassemble it. He practiced preservation techniques that were not just scientific, they were aesthetically pleasing and of great historical value.”

Sikes said there was still so much to learn from Alaska’s butterfly expert. “I think he thought that he would live forever. I know his friends hoped he would.”